While there are plenty of celebrated examples of non-profits (usually new ones) using technology innovation exceedingly well (think of charity:water, Ushahidi, Donor’s Choose or GiveDirectly), foundations are not known as a hotbed of technological innovation. In fact, they are rightly regarded as behind the curve when it comes to applying technology innovations themselves or supporting charities to increase efficiency and effectiveness. Why?

While plenty would argue that foundations as a whole are too conservative, there are numerous examples of foundations around the world innovating and taking creative approaches to difficult problems. Foundations invest a lot of resources, money and people, in figuring out how to work better. So why the lag in applying technology innovation?

One possible reason is scepticism about return on investment – and there are good reasons for this. The return on investment in ‘hot’ technologies is all too often far less than technology advocates led people to expect. While charity:water got many in the sector excited about the potential of social media to drive giving, no organization has been able to replicate that success. The explosion of text-based giving after the Haiti earthquake has never been replicated.

But this is a reason for more investment not less. And what’s lacking is not investment in technology but investment in people with the right skills and experience. Realizing benefits from technology innovations depends on people who understand the organization and the technology well enough to grasp both the technology’s potential and its realistic application in the organization. Knowing about technology is utterly different from knowing how and when to apply it.

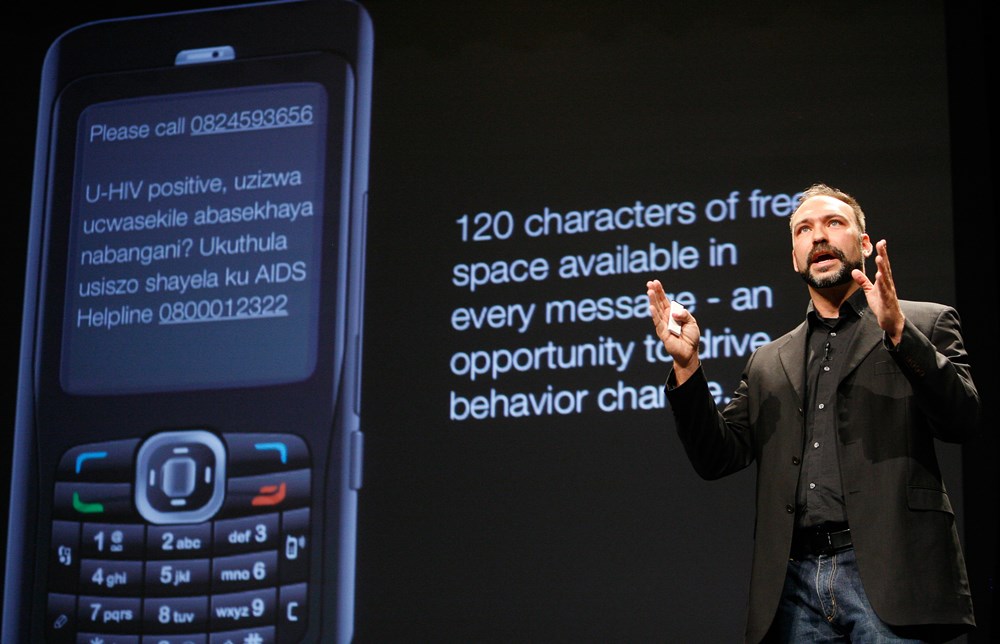

Gustav Praekelt describes the workings of Project Masiluleke’s SMS system, which uses widespread mobile device messaging to attract untested.

The most successful commercial organizations around the world have invested in people with the requisite expertise. In these organizations the chief information officer (CIO) has become a key part of the executive leadership team. A CIO is not just responsible for keeping email running and replacing broken-down PCs, but for integrating the organization’s technical and non-technical operations, deciding when technology can make a difference in achieving an organization’s goals and the best pace at which to introduce it. Understandably, CIOs with proven ability are highly sought after – except, as it turns out, by foundations.

This is not to say that there are no influential foundation CIOs, but you won’t find many of them, yet. And you will struggle even harder to find a leading foundation with a board member who has experience as a CIO – a truly vital part of the picture if social sector organizations are going to get better at deploying technology.

In 2014, to the extent possible based on publicly available information, I reviewed the boards of directors of foundations and direct-service non-profits looking for organizations that had board members with experience as a CIO. Among the 15 largest US foundations there was only one. The 10 largest direct-service non-profits in the US[1] also had only one. In the UK it was worse. None of the 10 largest foundations or charities had a CIO as a board member or trustee. While many of these organizations include board members from the technology industry, there is a substantial difference between the perspective of the CEO or founder of a technology company and the CIO charged with implementing technology to achieve measurable benefits.

‘This is a huge, and completely unnecessary, gap in the ability of the social sector to create change.’

This lack of expertise at the board level has a knock-on effect on the whole sector. Foundations that do not have expertise in the deployment of technology as part of their strategic governance are less likely to invest in technological innovation internally or to support (with cash) the deployment of technical innovation among their grantees. If they do invest, they are unlikely to make wise choices. Thus foundations’ lack of investment in CIOs as part of their organizational governance, by having CIOs either as part of their core strategic executive teams or on their boards, handicaps the non-profits they support and ultimately the society they serve.

This is a huge, and completely unnecessary, gap in the ability of the social sector to create change. If there is to be any hope that the social sector can improve its record in using technology to increase efficiency and effectiveness, foundations should start with finding the CIOs, allowing them to earn influence in strategy, and recruiting the best of them onto their boards.

Timothy Ogden is executive partner of Sona Partners and a contributing editor to Alliance. Email timothy.ogden@sonapartners.com

Footnotes

- ^ Excluding those whose actual governance mostly relies on local boards, such as the United Way.

Comments (0)