Courageous philanthropy

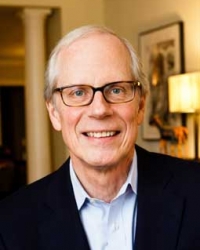

Foundations should take risks – it’s one of the sector’s truisms – but they often don’t. But there are exceptions. Stephen Heintz, the long standing CEO of the Rockefeller Brothers Fund (RBF) has overseen the Fund’s divestment from fossil fuels, helped broker a rapprochement between Iran and the US, played an integral role at the Paris climate agreement and led the way on efforts to tackle the ongoing lack of diversity in the philanthropic sector. Heintz shares these remarkable examples of bold action and other insights on philanthropy with Alliance editor Charles Keidan.

How long have you worked with RBF? What has it focused on and how has this changed?

I’ve been the CEO for 15 years now. My prior experience included 15 years in politics and government and then more than a decade in the non-profit sector. This turns out to have been good prior experience for the world of philanthropy. The foundation is focused on three thematic areas. The first is strengthening the quality of democracy. There is a close focus on the US, where we have very apparent democracy deficits, but we’re also interested in the question of how we can contribute to building a system of global governance that is more open, more transparent, more accountable, more inclusive and more participatory, given that so many major problems of the 21st century are going to be global and transnational in nature.

The second theme is sustainable development. This is our largest portfolio and, since about 2005, it has been entirely focused on climate and energy. Again, this has a large US dimension because the US is a major contributor of greenhouse gas emissions, and needs to be a major leader in the global solution to climate change. But we also work on climate as part of our global governance portfolio – we work on climate in China and in the Western Balkans and a little bit in India – in fact, if you look across all seven of our portfolios, climate now accounts for somewhere between 40 and 50 per cent of our grantmaking each year.

The third theme is peace building and here our work is focused on significant conflicts in the greater Middle East. We have a portfolio of activities in Afghanistan, we are doing work on Israel-Palestine, and we have been doing some really interesting work on the US-Iran relationship for the past 14 years. Overlaying these three focus areas, we concentrate on a handful of places that we think of as having a special significance. And so we are working in China, we are working in the Western Balkans, we are working in Egypt, and we are currently getting prepared to identify a place in Latin America where we will focus activity in years to come.

What volume of your work is in the US as opposed to overseas?

It depends on how you slice the data. If you look at the places where the grant recipients are based, it’s about 75 per cent US, but a lot of the US grantees are actually doing work internationally. We estimate that 65 per cent of the grants budget in 2015 was focused on work outside the U.S.

How much is your endowment and annual spend?

Our current endowment is around $850 million and our grants budget is a little over $26 million.

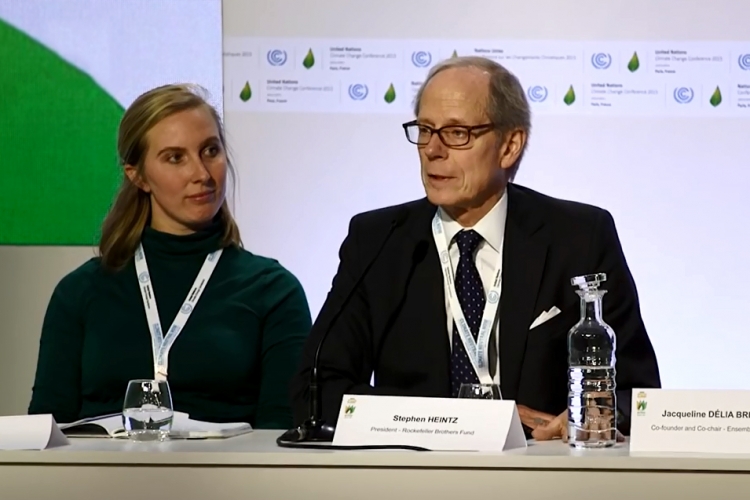

You were deeply involved with the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change. Could you say a little bit about your involvement and how it came about?

We have been involved in the entire United Nations Framework on Climate Change (UNFCCC) process going back to Kyoto. We have supported grantees in different areas including in the think-tank community who have been working on the substance of the global climate agreement. We’ve also focused on supporting advocates working globally to increase the ambition and push for agreement. And, along with some other foundations, we also provided support to the process itself. This helped to augment the resources available through multilateral and public budgets and made sure that the staffing capacity was up to the challenges of organizing and managing the diplomatic effort and producing an agreement. I think Paris produced a truly historic agreement and, especially after the disappointment of Copenhagen in 2009, it exceeded all our expectations. It sets the global community on a critically important path but there are some substantial gaps in ambition and the framework is not legally binding. This makes the role of civil society coming out of the Paris agreement even more important than it was going in to Paris. The key here is tracking progress, holding governments to account for the pledges that they have made, and continuing to press for private sector change – investment, divestment, technology development and deployment.

‘The Paris Agreement says 2°C is essential and 1.5°C would be better. But if you sum up all the Intended Nationally Determined Commitments (INDCs), they get us to 3.5°C. So there’s a mathematical gap.’

Apart from not being legally binding, what are the key gaps?

The other main gap is our target is to keep global warming to 2°C or under. The Paris Agreement says 2°C is essential and 1.5°C would be better. But if you sum up all the Intended Nationally Determined Commitments (INDCs) they get us to 3.5°C. So there’s a mathematical gap. We don’t only need to push for rapid, effective and full implementation of the commitments that have been made. We also need to ramp up ambition beyond those commitments.

There’s a view that some of the groups that will be most affected by climate change, particularly younger people, women, and indigenous people were too often outside the tent. Do you think that’s true?

Yes, I think there is a gap with regard to climate justice. You’ve mentioned various marginalized and deeply affected groups but there are also gaps in the equity between the developed world and the developing world and the whole question of how we finance the transition. The climate justice issues infuse that. Paris was a step forward in terms of climate justice but it’s still a significant gap.

RBF has played a significant role in the investment-divestment debate, not least with your recent decision to divest from fossil fuels which has been followed by a similar announcement from one of your philanthropic cousins, the Rockefeller Family Fund. What was behind the decision?

There were two motives. One was the discomfort of moral ambiguity. We were one of the leading foundations in terms of work on climate change and yet we were still, through our endowment portfolio, invested in companies that are producing fossil fuels that are generating the greenhouse gas emissions that are causing climate change. It’s not appropriate to be trying to find solutions on the one hand while you’re contributing to the problem on the other. But we also have to be practical, effective stewards of our financial resources, so we looked at the economics. One of our grantees, the Carbon Tracker Initiative, has produced a really important and carefully researched analysis which shows that in order for the global community to meet its commitment to remain within the 2°C limit, 60-80 per cent of the known fossil fuel reserves have to stay in the ground. The companies that own those reserves are going to be increasingly bad long-term investments because they’re carrying them on their books at high valuations.

‘It’s not appropriate to be trying to find solutions on the one hand while you’re contributing to the problem on the other.’

So there were compelling moral and economic reasons for the decision.

Exactly. It was a complex decision because so many stakeholders were involved. For one thing, half of our board are members of the Rockefeller family. The wealth they inherited, and which endowed the foundation, came from fossil fuels. At the time, there were different levels of enthusiasm for the decision, I am very proud of the fact that a consensus was reached that we should do it. Now that we have, the enthusiasm has grown.

The announcement of the decision in September 2014 became a global news story. Did you expect that?

Yes and no. Yes, because we knew it was a good story because of the irony of a Rockefeller institution divesting from fossil fuels. But the size of that story, and the fact that it is still being covered around the world, surprised us.

Sometimes foundations are seen as responding to trends, rather than leading them, but this put RBF at the forefront of debates around climate change.

I think that’s the right role for foundations not only on the divestment issue but also more broadly. Foundations’ independence gives us the opportunity to take risks and to demonstrate leadership in ways that others can’t. The private sector is constrained by profit motives – they will not take risks that are economically unacceptable. The public sector is constrained by politics so they can’t take risks that are politically unacceptable. Foundations can experiment. We can get out in front on some key issues. Collectively, we’re a small sector but we can leverage our resources by being leaders and taking prudent and careful risks.

To what extent are you encouraged by other foundations’ attitude to divestment? Would you like to see more following suit, including others within the Rockefeller stable?

This is the critical issue of our times so I am delighted to see the divest-invest movement growing. When we made our announcement, there were roughly 180 institutions committed to divesting with about $50 billion of assets under management totally. By Paris, that had grown to well over 500 institutions and $3.4 trillion. This is not just foundations. It’s universities, pension funds and other institutional investors. The movement is growing but I don’t think it’s growing rapidly enough.

Some, including some working in the field of climate philanthropy, are uncomfortable about discussing divestment publicly. Why do you think that is and how do you think it might be overcome?

We experienced that discomfort ourselves. We made our announcement in September 2014 but it was preceded by a long process of thinking about how to align our investments more directly with our mission that started in 2005. We went through shareholder engagement and proxy voting as our first step and then we started to set aside funds for proactive investing in things that were consistent with our mission. Only in 2014 did we come to the debate about divestment and made the decision that we did.

Is that because you were unsatisfied by the shareholder engagement or because you felt it was insufficient to achieve your objectives?

A little of both. We were not making major progress and we felt that more direct action was necessary. But there is still a great deal of conventional wisdom in foundation boardrooms and investment committees that there should be a real separation between the philanthropic work of the foundation and the actions of those who manage the endowment. Their job is to make as much money as they can to put into philanthropy. That traditional view needs to be addressed. Every institution needs to examine its own mission, decide whether the divestment question is central to it and, if it is, consider seriously whether they should join the movement. There are different answers for different institutions. I think it’s a question that at least needs to be on the table. What I would say and what I do say to my philanthropic colleagues is think about it seriously. We’ll respect whatever decision you come to but we all have to be thinking about it.

You talked about foundations taking risks and being able to go where others can’t, and that probably applies to peace building as much as anything. How has that applied to your work on US-Iran relations and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict?

The US-Iran area is a longer engagement for us than the Israel/Palestine so let’s begin with that. In 2002 I began to have conversations with people in the foreign policy community and our board about Iran. In the context of the conflicts of the Middle East, Iran has always been an outlier. It’s a Persian nation living in an Arab region. It’s a large and powerful nation with a highly educated and very young population. So it’s a major player in a very complex, conflicted region, in which the US has very significant national security and other interests. Yet, since 1979 the US has had absolutely no diplomatic or any other kind of relations with the country. American diplomats were forbidden from having any contact on any level with Iranian diplomats. So if an American foreign service officer in Paris was invited to a reception at the Italian embassy and an Iranian diplomat was at the same reception, they were forbidden from even shaking hands and saying hello. That’s how serious this was. So there was very little knowledge in the US about Iran and the same in Iran about the US, and no channels of significant communication. So we began to explore with a key partner, the United Nations Association of the USA, whether together we might be able to organize a dialogue between highly respected foreign policy practitioners and thinkers from the US and from Tehran – people who had served in high positions in government in the past, and people connected to the political establishment in both countries. It took us a year to lay the groundwork, but in December 2002, the first meeting happened in Stockholm through the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI). Over the next six or seven years, we had 14 of these meetings, and we were sharing the insights and ideas that came out of these conversations with very senior people in Washington and they were doing the same in Tehran.

‘We have been thanked by the White House and the State Department for having helped create an environment in which diplomacy could actually begin and ultimately succeed.’

This was all confidential. There would have been no way it could work if it was public. Subsequently, we have been thanked by the White House and the State Department for having helped create an environment in which diplomacy could actually begin and ultimately succeed. Agreement was reached about the constraints on Iran’s nuclear activity in one of the most important non-proliferation agreements reached in the last thirty years. It’s a very good example of what limited philanthropic resources – it wasn’t terribly expensive to do this, but high-risk, and high-reward – can achieve. We’re still working to protect this agreement, because there are people on both sides who don’t like it but it’s working so far. The Iranians have complied with everything they said they would do and it’s under international monitoring by the International Atomic Energy Agency. And we’re also now trying to build on the success of diplomacy to think about how gradually Iran and the US and others can work more effectively together to help solve other regional issues like Syria. As I said, it was high-risk. We were all nervous about it at the start. We had no idea what might happen – it could have all blown up in our faces.

One of the reasons this worked so successfully is that when we started, Iran’s ambassador to the United Nations was a brilliant Iranian diplomat, named Javad Zarif. When Hassan Rouhani got elected president of Iran in 2013, Javad Zarif became the Foreign Minister. So we had very close, personal relationships with him and on the American side, we have close relationships with John Kerry.

How did the work develop on peace building in Israel and Palestine?

It’s clear that there can’t be a more just, peaceful, and prosperous Middle East without solving the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. So we began to work on this in about 2011 and tried to do things that were supportive of the Obama-Kerry diplomatic initiative of 2013-2014. But frankly most of our grantees who are close to the issue were very pessimistic that the conditions were right for a negotiated settlement given the politics in both Israel and Palestine. Still, part of our grantmaking supported the process. Since the talks collapsed finally in 2014, we have been increasingly focused on trying to build constituencies for peace from the bottom up – working with youth groups, business groups, environmental groups, we have some environmental activism, some who are using various forms of economic activism, including some who support the BDS (Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions) movement, which is of course quite controversial – because until there is political will in both communities for the kinds of compromises that are going to be necessary to create the conditions for durable peace, it’s not going to happen. The only way to get to a just solution is to create the conditions for a thriving and secure Israel and a thriving Palestinian state, and the only way to get to that is by ending the occupation which is itself unjust.

What’s your view about divestment in the Israel-Palestine context?

Again, I think that is a decision that every institution needs to make. We do not endorse the BDS movement but some of our grantees are active in it in various ways. Some of our grantees are focused only on enterprises that are actually operating in the occupied territories in the settlements. Others are looking at divestment, so it’s a mixed bag, but it’s not the central focus.

You talked about supporting the diplomatic efforts in the Kerry initiative but, in spite of that initiative, some see US foreign policy as favouring Israel. To what extent is there a danger of becoming the instrument of state foreign policy in this work?

It’s a risk but not our risk because we and our grantees are challenging the status quo. We were supporting the process to move it in certain directions, which have to do with making sure there is a really just solution to this problem.

Are there other champions of this issue in the foundation world or do you feel people find it too intractable or too risky to become involved in?

There are certainly not enough for exactly that reason. The number of foundations that are really active in this work is very small. We have a fantastic board and they had a very serious conversation about the risks involved. They are concerned about it, and we do a continuous process of risk assessment and risk management especially in regard to this.

‘I went to Gaza a few years ago to see conditions there but I did not meet with the Hamas leadership.’

We talked about the occupation and expansion of settlements in the West Bank but how do you deal with Gaza and Hamas. What do you think of engagement with their leadership?

I went to Gaza a few years ago to see conditions there but I did not meet with the Hamas leadership. As much as I might criticize Israeli policy, I am not going to meet people who are lobbing rockets at innocent people in Israel on a regular basis. On the other hand, part of the work has to involve making Hamas less attractive to Gazans by creating a just solution to the overlying problem. We know the reason Hamas has support is because of the experience of Gazans and other Palestinians living either in the occupied territories or in territory where they are completely isolated, where the economy is a disaster, where they’re dependent entirely on the black market and living in real poverty in one of the most densely populated little tracts of land in the world. So until there’s a solution that includes a just solution for the Gazans, Hamas will be able to recruit supporters.

Can philanthropy have a role there given that it’s so untouchable to others?

We’re not operating in Gaza. We can’t operate in Gaza, so that’s a real problem.

We’re talking here at the 2016 Council on Foundations conference. You were just speakingon a panel looking at the question of diversity in foundations. What do you think of the current situation in regard to that and what needs to be done?

The good news is there’s a great deal more serious and constructive attention being devoted to the issues of diversity, equity and inclusion. The disappointing news is when you look at the data, particularly on diversity in foundation leadership and on foundation boards, we know that the numbers are not changing very rapidly. There is better progress with regard to diversity among foundation staffing and there have been some outstanding individual examples recently – we have a gay African American leading the Ford Foundation, we have an African American woman running the Kellogg Foundation, which is fantastic. Overall, though, data on leadership and on boards has not moved very much.

What needs to be done?

People have to really make it an intention to change. Like the divestment issue, you’ve got to put it on the table and deal with it. Take our own Foundation. Half of our board are members of the Rockefeller family, a white family. They are our greatest asset but that already limits our own capacity for diversity. Many of the other non-Rockefeller family members are significant leaders in the fields in which we work so the board is a fantastic board but we need to make sure that it is broadly representative of society and the communities we serve. That adds to our legitimacy as an institution, in the view of the public, to whom we are accountable. We also know from the research that diversity leads to greater creativity, better decisions and more success. We will have more impact as a foundation if we are really attentive to the question of diversity. Part of what the D5 hoped to do, and I think has done, is to extend the conversation on the issue.

For readers who aren’t familiar with it, what is the D5?

The ‘D’ is diversity and the ‘5’ is five years. It was launched by a coalition of philanthropic leaders and organizations in the US in 2011 with four major goals: to produce more diversity in foundation boards, staffs and leadership; to increase the flow of philanthropic resources to the needs of diverse communities; to improve the data collection on diversity in philanthropy; and to develop tools and resources and make them available to foundations and philanthropic leaders to help them take up this challenge effectively in their own work. I think we’ve made progress on all four just not as much as we’d have liked to have seen.

‘Diversity isn’t something that you accomplish, it’s something that you do.’

And what happens post-D5?

We’re thinking about how to embed the legacies of the initiative permanently in the field because the work needs to go on. One of the messages we were delivering at the Council on Foundations was that diversity isn’t something that you accomplish, it’s something that you do. As one of my colleagues said yesterday, it now needs to go from D5 to D-Infinity. It has to become an ongoing part of the philanthropic process.

Comments (0)