Safeena Husain knows exactly what she’s talking about. Herself the product of a troubled childhood and a curtailed education, she founded Educate Girls to tackle the problem of out-of-school children in India, one of three countries where the incidence of the problem is greatest. At the AVPN conference in Singapore last month, she talked to Andrew Milner about the ripple effect of girls’ education, about the virtues and criticisms of Impact Bonds and about the value of having an Asian platform for donors and NGOs to come together.

Safeena Husain knows exactly what she’s talking about. Herself the product of a troubled childhood and a curtailed education, she founded Educate Girls to tackle the problem of out-of-school children in India, one of three countries where the incidence of the problem is greatest. At the AVPN conference in Singapore last month, she talked to Andrew Milner about the ripple effect of girls’ education, about the virtues and criticisms of Impact Bonds and about the value of having an Asian platform for donors and NGOs to come together.

When did you set up Educate Girls and why?

My own journey is what led me to start Educate Girls. I had a very difficult childhood growing up in New Delhi and experienced first-hand poverty, violence and abuse. But eventually, with support from a friend of my father, I went from a traumatised child to being the first person in my family to go to university when I got in to LSE in London.

From there, my life changed dramatically. I moved to America, started my career in the non-profit sector and then returned to India in 2005. At that point, things began to crystallize for me. I realised that I had been able to achieve so much because of my education. I went to the Government and said if I wanted to work on girls’ education, where should I go? They shared data on 26 critical gender-gap districts, nine of which were in the state of Rajasthan, so that’s where we got started.

And that’s where you mainly operate?

Yes.

Access to education seems a problem that’s common to both genders in developing countries. Why girls? Why not children in remote areas generally? Does that derive from your own experience?

I should clarify that the work that we do is definitely gender-neutral in the sense that, when we’re looking at out-of-school children, we look at boys and girls and when in the classroom we teach both boys and girls. However, we approach all our work through a gender lens. Right now, we have one of the highest number of out-of-school girls anywhere in the world, we have the highest number of child-brides and women and girls trafficked. That becomes worse when you consider that we have less women than men, so there’s a chunk of girls missing because of the birth deficit and on top of that you’ve got this problem of access to education. When I started, I realised there is already CRY for child rights, and for education a number of non-profits at scale such as Pratham – but there was really a gap when it came to girls’ education and thinking about education with a gender lens so that’s where we fit in. But, yes, inclusion and equity means of course both boys and girls.

And presumably the implications of girls’ not going to school are much wider than lack of education?

Yes, it’s not just about education, though lack of education is a reflection of patriarchy, but of a much deeper mindset issue. In the areas where we work, people see a goat as an asset and a girl as a liability. And that mindset is very deep-rooted. We’ve had generations of this internalised patriarchy and education is one way to break it. When you do break it, the impact magnifies. The World Bank acknowledges that educating girls is one of the best investments you can make. Climate scientists have recently rated 80 actions to reverse global warming and at number six is girls’ education, higher than electric cars and solar panels, which is amazing. But that’s because fertility rates go down and that reduction in population automatically has a huge impact on carbon emissions. So you can take any development issue – malnutrition, stunting, child marriage – girls’ education can contribute to the solution of all of those problems.

For mindset change, community mobilisation to happen, you need a local agent and a local message.

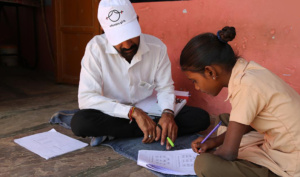

‘It’s a question of changing the mindset – village meetings, neighbourhood meetings, individual counselling.’ Photo Credit: Educate Girls

Could you tell me how you operate?

It’s really quite simple. First, we look at data and we see which areas are the worst for girls’ education. When we started, we used government data. Now we use advanced analytics and are able to produce predictive data using machine learning technology. Once we’ve decided where to work, we go door-to-door in those hotspots and we find every single out-of-school girl. Each of our target villages is geo-tagged, we collect this data on mobile phones, so it’s very smart, it’s real-time, and it helps us map out where the out-of-school girls are, where they are clustered, which are the most at risk. Once we know that, we assign trained personnel to bring them back into school. Then, it’s a question of changing the mindset – through village meetings, neighbourhood meetings, individual counselling – until those girls are enrolled back into school. When they’re in school, we work on things like infrastructure, school improvement, making sure that the school is girl-friendly because that helps to boost retention. When I started working, the majority of the schools didn’t even have a separate girls’ toilet. So we advocate for that. Even now, a toilet block might be built but without doors and right on the main road. So, there again, it’s that gender lens that’s absent. Finally, we focus on learning – Hindi, English and maths and boosting literacy and numeracy for all children., with an additional component of life skills for the adolescent girls.

You work with governments and with local volunteers. Does working with different sectors pose special difficulties?

We realised a long time ago that if you go into a village in tribal Rajasthan and you knock on some door and say ‘please send your daughters to school’, it’s not going to happen. For mindset change, community mobilisation has to happen and you need a local agent with a local message. For that, we create an army of gender champions, so in every village we work in there’s a village-based volunteer, our Team Balika (girl child). They are young, educated, passionate boys and girls and because they are educated, they really believe in its importance, and they leverage local relationships. They know who to speak to, and how to speak to them to make that change happen. We have 13,000 Team Balika volunteers working with us currently.

How do you identify and recruit them?

We do everything we can – ads in the newspaper, we go village to village on jeeps making loudspeaker announcements, we do poster campaigns, radio – whatever method we can find. When we work in a district, we will saturate it with all of these different communication means, then we host recruitment fairs, so a lot of people will come. After we’ve selected them we get the village to sign off on them, asking ‘do you think this person is responsible?’ So it’s a very intense outreach and selection process.

It’s about breaking that cycle and there’s a lot of data now that says once you break it, it stays broken

And asking the village to endorse them guarantees local acceptance?

Yes.

What about the other side, working with the government?

With the government, we have to build alignment. By identifying the government’s priority areas and supporting them to achieve their goals, we will have a joint vision of success. If the data tells us that the gender gap is greatest in a particular district, that is where we will seek to partner and gain permission from the government to work.

How is a funder sitting in the US or wherever dictating what should be the measurement framework or the outcome for a tribal child in Madhur Pradesh?

Before we enter a new area, we sign an MOU with the government, which means that our volunteer is not knocking on your door alone, she has a system behind her, so the sarpanch[1]knows what’s going to happen, the headmaster knows and we are working within an institutional framework. Also, our own organisational structure mirrors the government’s own structure, so we’re working with the government not just at the top and the bottom but at every level. It does take a lot of effort to build that alignment across and we may have bottlenecks here and there, but we’re constantly working to move them along.

And how are you funded? Is it through philanthropy?

It’s all grant funding.

Is that from within India or from overseas?

It’s both. There’s an international and a domestic element. It tends to be a bit of a mix – foundations and corporate foundations, CSR from companies, money from high-net-worth individuals.

Is the balance changing between the international and the domestic?

We’re getting much more domestic funding now.

Do you think the mandatory CSR as a result of the Companies Act has influenced that?

Yes, absolutely, I think that has really propelled it in a big way.

As you mentioned, there are cultural norms that prevent girls going to school in some communities. Is that your biggest challenge?

Yes, that’s the biggest obstacle to getting girls into school, or getting people to invest in their education. It’s really about renegotiating those positions and attacking patriarchy and that is the most difficult part. Like I said, we use volunteers to try to get over that, but the second part is that you have to be in there for the long term, because it doesn’t happen overnight and that’s why we will stay somewhere for six to eight years. If you do that, you’re actually creating a new normal. You don’t just run a campaign, everyone goes to school and you’re done, because that may not be sustained over a period of time. So during the time we’re there, we’ll have covered 10 cohorts and that’s a generation. If we’re able to hold a generation of girls in school, we know that in a few years, they will get married and have children, their children will then be starting from a different baseline. It’s about breaking that cycle and there’s a lot of data now that says once you break it, it stays broken, because an educated mother is more than twice as likely to educate her children. That’s what we’re really aiming for so we have to be in there for the long-haul.

EG pioneered the first Development Impact Bond (DIB) in education. How did that come about?

When I started EG, we were scaling really rapidly. We went from 50 schools to 500 schools, then to 5,000 school and I used to worry about whether we were having the same impact for the 10,000th girl who came into the programme as we did for the first child. At scale, how do you maintain quality? That was the question we started with. We applied to the Girls’ Education Challenge (GEC) run by the UK government’s Department for International Development (DfID) and in that programme, they had this payment by results concept – 5 per cent of the money was earmarked for payment by results. It struck me that if I could get into an outcomes based funding mechanism and if we were disciplined enough to sustain it, then it didn’t matter if we were working with one, a hundred or a million children, we would still know that the results we’d delivered were the same for the last child as the first. We applied to the programme, made the shortlist and were close to the contracting stage after nine months of work, when DfID wrote to us and said they were no longer funding in India – nine months!

We’d really come to believe that this was the answer not just to scale, but to maintaining quality at scale. So we spent about a year talking to a lot of donors on a kind of ‘roadshow’, trying to find someone to test this idea with us. We didn’t find anybody. Then, I met Phyllis Costanza, CEO of UBS Optimus Foundation, who, with the CIFF, became the main supporters of the DIB. She liked the idea. She told me that Social Impact Bonds (SIBs) did the kind of thing we were looking for but they had never been done in education before and never done outside the Global North. That was really the genesis. So the idea for me was very much how to tie quality to scale. This was not about more or new money.

For me, it’s really key that you have a vision of what success looks like and that’s totally missing at this point. What is it we want for that girl? We want her to be healthy, we want her to be happy.

Ours was a DIB. We couldn’t do a SIB[2] because, at the time, the Indian government wasn’t ready to think about it. We had nothing to show them, so we said ‘let’s create a template, let’s see what we learn and then the government will buy into it.’ The biggest question I think we answered through the DIB was, ‘why was this grant different from other grants? (and I like to remind people that the money that came to us was still a grant) – Why was this grant allowing us to have much higher impact than other grants we received?’ We concluded that it was because the money was multi-year, it was tied to a particular result, not an activity and it was flexible and unrestricted. We feel we now have the evidence to go to donors and say that we know how to create impact at scale if their funding is more results-based, more flexible and multi-year. I think one-year projects are the death of impact.

Putting together the DIB – they’re very complex things – how much work was that?

It’s an enormous amount of work. (and I’m not counting the nine months of the DfID application, or the year it took to find enough parties to come to the table!). From the time that we said ‘yes, let’s do it’, and everybody was together, to the time when we actually launched in the field was another year-plus and that’s the time it took to design the DIB because, as you said, nobody had ever done one in education before.

They’ve also got their critics. A recent article in SSIR claims, among other things, that they commodify people, they encourage a focus on the short term, they go for easy targets. What’s your response to that?

But what is missing is a nuanced conversation and there are a lot of things to unpack. For me, it’s really key that you have a vision of what success looks like. What is it we want for that girl? We want her to be healthy, we want her to be happy. Those are big long-term things, but we all need to come together and say these are the outcomes we want to see and then fund for that, in a way that’s multi-year, flexible and tied to that vision of success. Think of a toolbox approach. Maybe the best tool for, let’s say, livelihoods is a DIB. To push the social justice agenda, maybe it’s grant funding. The key point is that the tool is the means, not the end. DIBs and SIBs are like pressure cooker transactions. You can learn from them, and use them as R&D tools. There are lots of permutations and combinations that we could think through, but the thing you really need to be guided by is your vision of success.

Would you do another DIB?

I would if certain conditions were in place. Right now, it’s very hard for organisations like ours to jump from one DIB to another because outcomes change with each transaction. Let me explain. DIBs are payment by result transactions. One DIB may have as a success rate of A level results. Another might be structured to success rate of SAT results for its students, another to Indian State board exams, etc. Now if I’ve built all my learning content, training, my programme at scale for A Levels, it’s not going to be easy for me to start delivering to SATs. It requires a redesign of the entire education package at scale. We’d have to change everything, so for a DIB which, like our DIB, was two per cent of my budget, it doesn’t make sense.

The other thing is who is deciding the outcomes and the measurement framework? Are they aligned to SDGs, to local government? I think the prerequisite for us doing another DIB is, first, the outcomes need to match what we actually can deliver and, second, they should be signed off or prescribed by the government or by the SDG framework. Right now, each transaction is bespoke which makes it hard for non-profits to do multiple DIBs. But with the SDGs, you have indicators, and, if within the indicators, you have a measurement framework and all the DIBS were tied to that, I think that would create a more standardised market place. Also if government has signed off on the outcomes, we would also mitigate against them triggering any perverse incentives on the ground. I think that’s what’s really needed –a standard common outcome and measurement framework signed off by government or SDGs.

Coming on to AVPN, what’s the value for you, first, of the network itself and, second, of this conference?

It’s my first time, but….it’s great. First of all for me. I don’t have that much exposure to South east Asia generally, so it’s been interesting coming to Singapore and seeing what’s really happening and being able to explore. The formal sessions and informal gatherings were great places for us to look at what kind of philanthropic thinking is happening, what are the priority areas here, what are the touch-points, so that learning has been really, really good. We’ve had plenty of exposure in Europe and the US, but not much on this side of the world.

And how much value does having a network in Asia have?

I think the big things that AVPN is doing for us is exposing us to a different group of funders and also the way that they’re curating the conversations. I’m actually sitting with a lot of funders, saying this input-based, one-year project cycle doesn’t make sense, so I think they’re almost taking people along to where the strategic funding needs to be, they’re navigating that conversation.

So it’s a good mix of NGOs and funders?

Yes, definitely.

Finally, where do you want Educate Girls to be in five years’ time?

Currently our five-year goal is 35,000 villages and to solve 40 per cent of the problem of out-of-school girls in India – 1.6 million out-of-school girls – which is one of the three highest populations in the world, after Nigeria and Pakistan. We’re on the way to doing that. Becoming part of the Audacious Project has really given us a big leg-up. That’s the project they launched at TED this year, so out of 1500 NPOs, they chose eight projects to fund to help realise their ‘audacious vision’ and we were one of them. Together, they’ve raised about USD300m in total for the eight projects.

How did you come up with the 40 per cent figure?

Our data shows us that 40 per cent of the out-of-school girls are in five per cent of the villages, so we’re saying that, as one organisation, we will saturate those five per cent in the coming five years. These villages are the most in need, they will have the most risk of child marriage, child labour, malnutrition, stunting and, by enrolling and educating girls, you will break the cycle on so many indicators – income, poverty, nutrition, health…and climate change. If we can achieve this in five years, what a big boost it would be in terms of development generally.

Andrew Milner is associate editor of Alliance magazine

Footnotes

- ^ Elected village leader

- ^ The difference between a SIB and a DIB is in who ultimately pays for outcomes. In a Social Impact Bond the outcome payer is the government, in a Development Impact Bond it’s a donor. See Instiglio’s definition at www.instiglio.org/en/impact-bonds.

Comments (0)