Rhodri Davies of Charities Aid Foundation (CAF) has just published a book on the history of British philanthropy, Public Good by Private Means. In doing so, he discovered more to that history than a series of interesting anecdotes. In fact, closer consideration tells us much about the purpose and role of philanthropy in the present day. He talks to Alliance editor Charles Keidan about pluralism and freedom, about the telling of uncomfortable truths and about the need to treat philanthropic power responsibly.

How did you become interested in philanthropy?

I slightly fell into philanthropy. I started out wanting to be an academic in philosophy, philosophy of maths particularly, but quickly realised that while I found it interesting, I didn’t necessarily want to spend the rest of my life doing it. I landed on the idea of working in a think-tank as a way of combining my interest in academic research with something with a real world focus. At the time, Policy Exchange had a project looking at philanthropy in the City of London, and the culture of philanthropy in the financial services industry. I managed to get my foot in the door that way. I joined CAF in 2010, and I’ve been here ever since.

What do you do at CAF?

I lead a programme called Giving Thought which looks for new policy ideas on the role of and the environment for philanthropy both in the UK and internationally. We look at what’s new or coming round the corner that could have an impact on the way that people are able to engage in social action.

How international is CAF?

CAF’s very international. We’ve got nine offices around the world. They are loosely affiliated but independent so they all look a bit different and reflect the areas in which they work. One of the things that we’ve done in the last couple of years through Giving Thought and Future World Giving is to use our network of international offices to do some policy work on the overall global environment for philanthropy. We’ve done reports on the factors that affect giving around the world including independence of civil society, financial independence, trust in not-for-profits, and the tax regime and incentives on offer.

Charities Aid Foundation is an unusual name. Where did it come from?

In 1922, the British government introduced the ability for donors to claim deductions for their gifts through a covenant, which is an agreement with a specific charity. People quickly realized that you could covenant to an intermediary which would receive deductions and, through it, you would still be able to give to all sorts of different charities. It’s the birth of the donor advised fund idea. The National Council for Social Service, which later became the National Council for Voluntary Organizations (NCVO), set up its own covenanted fund which, I think, was called the Charities Department. This department gradually morphed into doing other things and became the Charities Fund in the 1950s. In 1974, it was spun off as a standalone entity, the Charities Aid Foundation.

Speaking of history, your recent book has a substantial element on the history of philanthropy in the UK.

Absolutely. I think that one of the things that I learned in researching this book was that I knew far less than I thought about the history of philanthropy. A number of times, I came across stories from the past that made me think that we’ve had a lot of the arguments before that we’re currently having in one form or another. There are things that have been tried before in terms of approaches to social issues that we seem to have forgotten.

Can you give me an example?

Impact investing. The idea of combining a social purpose with a financial return is as old as the hills. It probably predates our modern notion of commercial business. Thomas Firmin, a merchant in London in the mid-17th Century did straight-down-the-line traditional philanthropy focused on poverty but he also set up businesses to employ weavers and spinners. He knew they weren’t going to be able to generate a proper financial return but he saw it as a form of below-market-rate investment. His idea was to try to get the government to take up this model but it never happened.

Another example is the arguments about the tax status of charities and donations to charities. There’s a big debate in the US at the moment and there was a similar debate in the UK in 2012 about capping relief on charitable donations. Tax was also a point of contention in the Victorian period. Gladstone, a Liberal, was fundamentally opposed to the idea of tax relief for charities, whereas Disraeli, a Tory, saw it as a basic principle that money given away for charitable purposes shouldn’t be taxed.

At the time, a lot of the philanthropy was in the form of bequests and allowing favorable tax treatment essentially allowed the perpetuation of inherited wealth, a kind of plutocracy. Gladstone thought it was unfair to allow those advantages to charities that relied on bequests but not those that got money from living people. Unfortunately, his solution was not to extend the relief to living people but to get rid of the relief for bequests. Disraeli, on the other hand, was in some ways a prototype of small-state Conservative who believed in people helping themselves and minimizing government wherever possible.

It’s an interesting story but how far do you think such episodes are relevant now?

You have to be careful. Historical anecdote is often fascinating but there’s a danger of reading too much into it without taking into account the very different context. At a very basic level in the UK, one of the benefits of understanding the historical context is it shows that philanthropy is part of a long continuum rather than something that has arisen as a new phenomenon. I think there’s a danger in the UK that philanthropy is presented as something that has been imported from the US. While we often adopt trends from the US and we increasingly look like we’re mirroring things that are happening in the US, that’s partly to do with the greater professionalization of the industry there. We do have our own far longer history of philanthropy here.

What insights into philanthropy does the development of the welfare state in the UK provide?

I think the really valuable thing from tracing the full history of philanthropy is that you see that, as soon as the government did accept responsibility to some degree, government welfare provision and philanthropy existed in harmony or disharmony to a greater or lesser degree over hundreds of years. It wasn’t binary. A switch wasn’t flicked and suddenly the government took over and philanthropy was irrelevant. The balance of power, responsibility and expectation both from the government and the general populace about what philanthropy should be expected to provide and what the state should be expected to provide moved backwards and forwards.

A good example is the first legislation to do with charity in the UK, the 1601 Statute of Charitable Uses, which has formed the basis of charity law both here and in the US, and the Poor Laws in the late 1500s/early 1600s. The government had introduced the Poor Laws by which they took responsibility in principle for the most egregious cases of poverty. At the same time, they wanted to try to ensure they never actually had to act on that responsibility. The Statute of Charitable Uses was meant to bolster philanthropy so that it would deal with these cases. Over time, the government got more involved in welfare and they did have to enact some of the Poor Laws. However, the very famous blossoming of philanthropy in the UK in the Victorian era from 1850 to 1900 was a reaction to growing state involvement. There was a sense that such involvement was not desirable and there should be an attempt to provide a universal system of welfare through philanthropy. If you walk around London or many other cities in the UK, you can still see a lot of the public buildings, libraries, museums, art galleries, that were created in that period by some of the very famous names in UK philanthropy.

And was there really a view among Victorian philanthropists that philanthropy could provide a universal system of welfare?

I think so. A lot of criticism of philanthropy around the turn of the twentieth century took the view that providing for the needs of citizens through private giving had been tried, hadn’t worked and therefore the government needed to step in. The lesson that is relevant today is that the discussion about the respective roles of philanthropy and the state is hijacked by people who are very firmly of one view or the other – either that the state must accept all responsibility or that government involvement in virtually everything should be reduced in order to reduce taxes and public expenditure. I believe the reality is somewhere in the middle where both have a role to play. The interaction between the two, although extremely complex, is what really pushes society forward. I think that the black or white view is not only wrong now but a misreading of history.

Is your analysis also applicable to other countries that have developed in similar ways?

I would say so. I think the question of the balance between government responsibility and the responsibility of private wealth is a universal one. It might be possible to pick different points on that long timeline we have in the UK and draw lessons from it for other contexts. For example, although the size of the UK state would probably be something most people in the US wouldn’t want to contemplate, the government there actually does provide for an enormous amount of the needs of citizens. The debate sparked by Obama care has raised the question about what is within the ambit of government and what should be for people to provide themselves either through philanthropy or through social insurance.

‘I think the most basic is that it is an absolutely crucial part of philanthropy’s role. To my mind, it is at least as important as the provision of direct services to those in need.’

We’ve talked about philanthropy’s role alongside welfare, but what about its role in challenging the status quo or even the government? What historical insights have you identified in that area?

I think the most basic is that it is an absolutely crucial part of philanthropy’s role. To my mind, it is at least as important as the provision of direct services to those in need. It’s a very topical question because there is increasing questioning from some in government, and also in media, of the legitimacy of the campaigning role of charities not only in the UK but around the world. The phenomenon of the closing space for civil society globally is often about governments’ trying to be positive about charities and non-profits but only insofar as they deliver services and take the burden off the state. What states are clamping down on is the use of charities and non-profits to question government policy.

‘You have to recognize the importance and the value of philanthropy as providing people with a means to question politicians of the day and their decisions.’

What can you see on that historically?

If you look at some of the most notable examples in the UK of campaigns that were, at least partly or initially, philanthropically funded, they are things that had little political support and would never have happened through the traditional mechanisms of democracy – the anti-slavery movement, the extension of universal suffrage to women, the decriminalization of homosexuality. All of these things took a long time and eventually became political questions. They would never have got on the table if it hadn’t been for philanthropic organizations and people coming together through voluntary associations funded by philanthropy to build a grassroots case for support and to convince politicians that public feeling was sufficiently strong that the issue needed to be taken seriously. From a politician’s point of view, philanthropy’s providing of a critical voice is inevitably going to be uncomfortable. But I think the lesson from history is that, if you take a long-term view as someone who believes fundamentally in the health and strength of democracy, you have to be slightly bigger than that short-term discomfort. You have to recognize the importance and the value of philanthropy as providing people with a means to question politicians of the day and their decisions.

How does the issue of pluralism and freedom – freedom within civil society to offer contradiction or to campaign for contradictory things – relate to this?

I think pluralism is absolutely fundamental. One of the problems that arises in trying to address philanthropy through public policy is that people either accidentally or wilfully misunderstand what it is and what its role is because governments are trying to use it as a precise tool to meet their own agendas.

Really, though, philanthropy is, at one and the same time, an incredibly potent force for innovation and change and extraordinarily diffuse, because it’s based on the motivations and impulses of individuals and that makes it extremely difficult to target in an effective way. It’s a reflection of the full breadth of society. The freedom of association means that people are free to associate around whatever they feel to be important or right or the values that they feel should be represented in their society and that encompasses a huge spectrum of things.‘It’s a reflection of the full breadth of society.’

‘I’d take the view that any tax relief on donations offered by government should be seen as a generalized subsidy for a truly pluralist civil society.’

Your book contains recommendations for public policy today. How does philanthropy’s roots in freedom of association influence your recommendations?

Very directly. Philanthropy is a voluntary act based on the motivations of individuals. I feel that it should seek to move society forward and should attempt to change something that people see as not right about the society they live in.

In terms of concrete policy-making, I’d come back to the pluralism issue and the way donations are treated through the tax system. In the debate, there’s a suggestion that deductions or tax relief for donations is offered because it’s a way of subsidizing services that the government would otherwise have to provide. Now, if you truly believe that that’s the only justification for offering tax relief for donations, you can’t justify subsidizing campaigns against government policy through that system and I would argue that that is one of the most fundamental roles of philanthropy. I’d take the view that any tax relief on donations offered by government should be seen as a generalized subsidy for a truly pluralist civil society. Any sophisticated, mature government would see that as fundamental to the health of democracy even if it’s often quite uncomfortable. You need to support the whole lot, you don’t get to pick and choose. I think that’s relevant not just here in the UK, but everywhere else when governments come to choosing whether or not to support individual donations through the tax system, and relevant to how they choose to do that. I think the view of tax treatment of philanthropy has to recognize the additional value of pluralism and associational life and of giving people a sense of agency outside of the tax system.

So plurality and agency are important, but sometimes government spending, at least in liberal, democratic regimes, is associated with equity. Do you think there’s a balance of values here between the equitable distribution of resources that a government can provide, and the plurality and agency that philanthropy offers?

I’d suggest two things. First, an important lesson for policy-makers is that you always have to be aware of philanthropy’s limitations. Philanthropy is very good at delivering some things: it can deliver a longer-term view perhaps than public spending which is tied to political cycles. It can be good at innovation. It can be good at risk-taking. Philanthropy is not good at ensuring equity because it’s not set up to do that in the way that public spending, funded by taxation, is. The second thing is that, once government has accepted in principle offering a subsidy for a pluralized civil society through tax treatment of donations, there are different ways of doing that in practice, which are more or less progressive. Offering that subsidy through deductions is not especially progressive because it favors the wealthy, whereas offering it through direct tax credit is much more so. Governments have to take that decision on the basis of how important to them equity is.

From your research, have you got examples of philanthropists that offered some of the best in terms of the promise of philanthropy, as you described it, and some of the worst?

One of those I admired most was John Howard, an 18th Century prison reformer. He wasn’t vastly wealthy but used his own money to fund research into prison reform. The admirable thing about him was that he did not do what a lot of philanthropists in his day did which was decide they cared about a social problem and then just bring to the table preconceptions about how to deal with it. Rather, he set about trying to build as strong an evidence base as possible in order to try and actually understand what was going on in prisons to almost a ridiculous degree. John Howard got himself captured on a plague ship going towards one of the plague prisons in Vienna because they wouldn’t allow him in as a visitor. He wanted to look round prisons in France. The French authorities threatened to throw him in the Bastille as a spy if they caught him so he went in in disguise. Maybe that’s a difficult aspiration for today’s philanthropists but his level of dedication combined with a refusal to just rely on preconception was, I think, amazingly admirable. He was not an especially likeable man on a personal level by all accounts but the flipside was that he was also totally unafraid to speak truth to power. He was almost universally lauded during his life in a way that few philanthropists have been before or since. He hated the adulation but it gave him access to the higher echelons of society which he would use to browbeat royalty or political magnates about the things he cared about.

‘Some of the philanthropy scene in the Victorian era was extraordinarily self-indulgent.’

So bravery, incorruptibility, humility? What was the flipside?

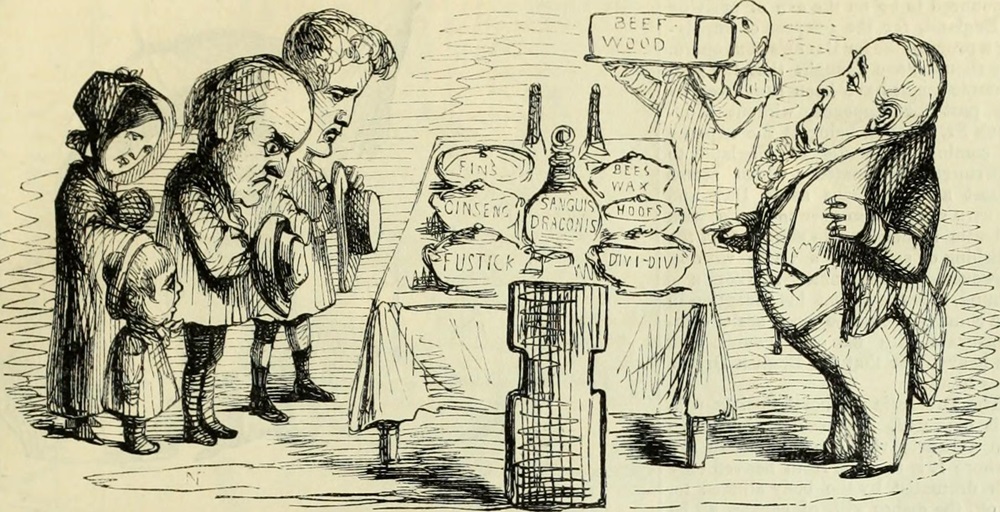

Some of the philanthropy scene in the Victorian era was extraordinarily self-indulgent. The focus was largely on how it made philanthropists feel. For instance, it became very fashionable for the wealthy or for the middle class to visit the poor in their homes, often uninvited, not to provide help, but in a way that was extremely demeaning. There’s a lesson here. Philanthropists have a responsibility because there is a clear power imbalance when you are the one with resources trying to give them to other people. You have an obligation not to do it in such a way that you dehumanize or degrade the person who is the beneficiary. An even more extreme example was what were called voting charities in the early 1800s. Proposed beneficiaries would be put forward by members and paraded in front of all of their friends. Apparently the meetings of the charity looked like a casino or a dog track. There are ways of giving that are more or less empowering for the people on the receiving end. I think managing that relationship is one of the real challenges for philanthropists.

‘Proposed beneficiaries would be put forward by members and paraded in front of all of their friends. Apparently the meetings of the charity looked like a casino or a dog track.’

Reading the history of philanthropy is far more than just the stories of dead donors and what they did with their money. If you read it with one eye on what’s happening in philanthropy now, and what the key issues are at the moment, I think you can really distill a lot of interesting lessons from it.

Public Good by Private Means by Rhodri Davies, published by Alliance Publishing Trust, is available on Amazon with kindle and paperback versions, and an ebook version is available on iTunes, GooglePlay, Kobo and Barnes & Noble.

Comments (0)