David Kaplan is Director of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), the international arm of the Center for Public Integrity (CPI), based in Washington DC. Launched in 1997, ICIJ has grown to be a global network of more than 100 leading investigative reporters based in 50 countries. Caroline Hartnell met David Kaplan to find out more about ICIJ’s unique brand of ‘watchdog journalism’ and why it should matter to foundations wanting to achieve social change.

Can you tell me what you mean by watchdog journalism?

Watchdog journalism is the journalism of accountability: looking with a critical eye at major institutions and individuals that exercise power in our societies and asking if they’re using that power in an accountable fashion.

We also talk about investigative journalism, where the emphasis is on long-term in-depth research and reporting. Our approach is: something has happened, here is my working hypothesis, how do I go about proving it in an honest way? If the evidence doesn’t support it, I have to re-evaluate my assumptions. But if it does pan out, then we’re going to publish a broadly constructed, deeply rooted investigative feature that spells out in depth why something has gone amiss.

We recently completed an eight-month investigation into the asbestos industry. Since asbestos markets dried up in Europe and North America, producers have been exporting it in huge amounts to developing countries, despite the fact that independent scientists predict that 5 to 10 million people will die from asbestos by the year 2030. This is an extraordinary story to us: the industry is in effect dumping its product on places like India and China where there are very few workplace safeguards, and the industry knows this. We put together a team and traced how the industry had spent nearly $100 million on international marketing since the mid-1980s.

We recently completed an eight-month investigation into the asbestos industry. Since asbestos markets dried up in Europe and North America, producers have been exporting it in huge amounts to developing countries, despite the fact that independent scientists predict that 5 to 10 million people will die from asbestos by the year 2030. This is an extraordinary story to us: the industry is in effect dumping its product on places like India and China where there are very few workplace safeguards, and the industry knows this. We put together a team and traced how the industry had spent nearly $100 million on international marketing since the mid-1980s.

The story took us eight months to put together, and that’s why you need specialist teams of investigative journalists. You can’t do that as a beat reporter, while you’re turning around quick stories to meet a deadline. You need a dedicated team in order to help put an entire issue on the map. I think we did that in this case – ultimately it was covered in 20 languages, and we reached more than 30 million people.

You published your findings in July. Have things started to happen as a result?

Having impact is very important to us, and getting the story out to so many people was a good place to start. We were especially pleased to get it released in Chinese and Hindi; there’s an educational component to what we do so there are key audiences we wanted to reach with this reporting.

At the same time, it was front-page news in Canada, one of the world’s leading exporters, which sends much of its asbestos to India. It’s a hot issue there now: in response to our story, the leader of the Canadian opposition called for an end to Canada’s exports; the government of Quebec is thinking of closing the last mine in the province; and more than 1,500 people have written letters to Canadian officials demanding an end to the trade. The story also prompted a bill to be introduced in the Brazilian parliament to ban asbestos. It has stirred controversy from Delhi to Mexico City. We did it in conjunction with the BBC’s international news services and they were a great partner for us.

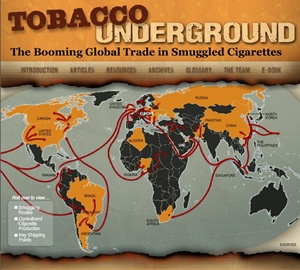

Social change happens on multiple levels and sometimes when you introduce or expose an issue, you don’t see the ramifications for months or even years. Our work on the tobacco industry – how big tobacco has worked with organized crime syndicates to further its market share and evade taxes – helped prompt public interest lawsuits, law enforcement investigations and lots of public education campaigns, so I think we can draw direct lines from work that we’ve done to changes in society.

Social change happens on multiple levels and sometimes when you introduce or expose an issue, you don’t see the ramifications for months or even years. Our work on the tobacco industry – how big tobacco has worked with organized crime syndicates to further its market share and evade taxes – helped prompt public interest lawsuits, law enforcement investigations and lots of public education campaigns, so I think we can draw direct lines from work that we’ve done to changes in society.

But our strength is on the journalism side … we’re not activists, we’re not advocates. Our strength comes from being independent reporters who can look at these issues with a critical eye.

We also do a lot of outreach to ensure that the right people are seeing our material – regulators, policy makers, NGO staff, scientific bodies. That’s a very important component of what we do. We recognize that we can’t just be witnesses to what’s going on.

Doesn’t the conventional media fill this role? I read the Guardian and do see big stories broken through investigative journalism. Is this rare?

It’s increasingly rare. There were never ‘the good old days’ with investigative journalism – it’s always been a struggle. I’ve been doing this for over 30 years in the States and overseas and we’ve always had to fight to get the time and resources to do serious in-depth journalism, but it’s become much harder recently. There was something of a flowering after the Watergate scandal, and internationally the tools and techniques have spread with globalization, so that’s been pretty exciting.

But we’ve been hit by a couple of tough punches. One relates to our business model. For years advertising has supported much of the best investigative journalism, but the bottom has dropped out of advertising with the advent of the internet age. We’ve lost billions of dollars from newspapers, magazines and television; some of that has migrated to the web, but the online revenues are a fraction of what used to be earned in print. So how do we finance this kind of serious journalism? There are no easy answers, you simply can’t generate that kind of revenue online – we haven’t seen the right kind of models yet.

The second punch that came along was the recession. We were already shutting down jobs in newsrooms in Europe and the US at an alarming rate, and then the recession came and it’s really caused a haemorrhaging of serious media. We’re losing our investigative teams and foreign bureaus are being closed. At a time of unprecedented globalization, we’re losing our eyes and ears around the world.

Is the rise of social media also undermining the idea of investigative journalism – given the fact that with blogs and Twitter anybody can publish their story on the internet? There’s a perception that we’re all creating news, we’re all journalists now.

The irony is that people are consuming more information than ever before – but what’s the quality of the information they’re taking in? Our attention spans are much shorter now. I think there is a market for serious in-depth journalism – we have examples like the Guardian and like 60 Minutes in the States, where every Sunday night some 12 million people turn on the TV to watch investigative reporting. I’m confident that we will see new models that will support this kind of reporting, but we’re in a real transition and I think that’s why the foundation community and individual donors are responding – they see that in-depth investigative journalism fills a social need. Someone needs to supply the watchdog function.

Broadly, what role can journalism play in advancing democracy and driving social change?

I’ve worked in international media development for 20 years and found it such a challenge to develop independent and vibrant media in transitioning and democratizing societies – you need to bring all these elements up at the same time. You need civil society, reasonably honest legislators, police and prosecutors, and you need media that has legal support, a watchdog function and some independence. You can’t just develop independent media in a vacuum. Unless journalists have the support of an independent judiciary, we’re just setting them up to get thrown into prison – or worse. I stay up at night worrying about my reporters; we’ve had people under attack in Pakistan and Sri Lanka and we’ve been chased by gangsters in Paraguay. Often the safety net is pretty thin, so we work on trying to improve that. The key point is that you have to bring up all these institutions at the same time to have some success.

Media development is a fairly new field in development generally – it’s really only in the last 20 years that donors have started to look at independent media as a sector of value in and of itself. Media used to be seen just as a component of a bigger project, like battling malaria or HIV, but I think there’s been a fundamental sea change here. Within that, investigative media has a very special place in holding people to account and helping to push the development of a free and open society.

So are you saying that if you don’t have democracy, it is hard to have any investigative journalism?

That’s mostly true, but at the same time we see lots of examples of ways to build beach-heads in not entirely democratic societies. For example, Chinese journalists can’t report on the communist party and the real powers that be but they have exposed crooked football games, tainted blood supplies and local corruption. An entire generation is being trained to use internationally recognized investigative tools to cast a critical eye on major institutions.

Another example is Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism, based in Amman, Jordan. They work with journalists doing projects in Syria. They can’t report on the Assad regime but they can write about food supplies or sanitation. In Vietnam you can write about consumer issues and medical problems. There are ways into these societies to start building a cadre of skilled journalists.

ICIJ is part of a network of groups comprising a global community of investigative reporting organizations. When the Cold War ended there were probably not more than a dozen of these groups worldwide; today there are more than 50, among them the Philippine Centre for Investigative Journalism, Consejo de Redacción in Colombia, the Romanian Centre for Investigative Journalism. We’re starting to network and pull everybody together. We’ve had six international conferences where we’ve attracted thousands of journalists from over 80 countries. In part because of globalization, the internet and cell phones, the traditions that have blossomed in North America and Western Europe are going global. We may be struggling in the West to keep our investigative teams alive, but they’re growing in Brazil and China and India.

How is ICIJ funded?

ICIJ receives about $1.2 million a year, and it’s entirely foundation funded. We are the international arm of the Center for Public Integrity, a $5 million investigative journalism nonprofit organization based in Washington. We don’t take any government money or corporate money. ICIJ’s biggest funder today is the Adessium Foundation, which has been very generous in giving us a three-year capacity building grant. Their staff had seen our work while travelling overseas and approached us and asked whether they could help. It was a wonderful call!

We have some individual donors as well, who are excited about the way in which investigative journalism is a force in fostering accountability and promoting transparency and democracy, and we’re working to increase that. It’s really interesting how potential donors react to us; some instinctively grasp why what we do is important and for others we have to do a lot of explaining about the unique role we occupy. We jealously guard our role as independent journalists. We have credibility because we’re not an advocacy group and we’re not campaigners or activists.

I think foundations know that our work can drive social change. We work on this at several levels: we do the reporting, the months-long investigations into challenging transnational issues. We also spend a lot of time on networking, we’re one of the hubs in this global community of investigative journalists. So we’re spreading the kind of methodology that has been used so successfully in the West worldwide, and this is another place where we can really make a difference.

So do most of the foundations who support you give core funding because they understand the importance of the work you do? Or do some give funding in a particular area like the environment to enable you to work in that area?

We’re careful not to take funding to do a particular story. We have broad policy areas that may align with a foundation’s mission. Our board has affirmed these policy areas as: money and politics; business and finance; energy and the environment; and international crime and corruption. Healthcare is another emerging field for us. Out of that framework, we narrow the focus in our proposals, and then the editors decide what the specific stories are going to be.

We’re careful not to take funding to do a particular story. We have broad policy areas that may align with a foundation’s mission. Our board has affirmed these policy areas as: money and politics; business and finance; energy and the environment; and international crime and corruption. Healthcare is another emerging field for us. Out of that framework, we narrow the focus in our proposals, and then the editors decide what the specific stories are going to be.

So, for instance, if I was from a foundation dedicated to trying to stop women trafficking in India, and I thought that a particular industry in a particular area was involved, could I come to you and say I would like you to look into the connection between this industry and women trafficking?

I think we’d be very interested in an idea like that, but we would take a step back and ask how we frame this as a broader issue. We’re not investigators for hire; we won’t go into something just because it’s on a foundation’s agenda.

The Center for Public Integrity is funded by some of the major foundations that have an interest in journalism, transparency, civic engagement and government accountability –MacArthur, Rockefeller, Carnegie, Adessium, Knight, Ford, Open Society Institute. Some foundations support us because of their particular mission, for example the Rasmussen Foundation, which has an interest in the environment and toxics. They’ve learned about our work and fund our ability to report on environmental issues on a general level.

We know foundations like this are going to be interested in what we do because of their own mission, but they understand that they cannot drive the direction of the story. Their mission is served by seeing that journalists have the means to report. We have to be clear that we have a firewall, that we will go where the story takes us, and that that might ultimately be in a direction that is not relevant to them. But if they are genuinely interested in advancing the truth, we get along fine. We’ve had very good experiences with our funders, many of whom we rely on for ideas and contacts. They are sophisticated people who understand that we’re effective because we’re independent.

Your hypothetical women-trafficking case might come under our international crime and corruption umbrella. For ICIJ, this field is of real importance because these are such huge issues in developing countries, where much of our work takes place. Much depends on our current priorities: do we have a project that it fits into? Are there enough resources available? Is it a compelling investigation? Can we bring new depth to a story?

The crooks know how to move money and illicit goods and smuggle people and arms. The good guys are far behind. Law enforcement, politicians and the media are largely national in scope, so who is actually out there trying to get teams of journalists to follow these trails that are leading to Switzerland and yanking resources out of places like Nigeria?

One of our current projects is looking at what we call Looting the Seas – at the striking lack of accountability within the fishing industry in the Mediterranean and the Pacific. So many of the fish sold in the world are in effect caught off the books — it’s a huge black market.

Overfishing is a story that’s been told before from different angles: environmental, political, sentimental. We’re telling the story of a criminal economy, about the dollars behind the actors.

So although anyone could tell the story of overfishing, it’s only if you’re finding out where the money comes from that you’re really finding out what’s driving it, and so exposing the levers for changing things?

It’s the old adage attributed to ‘Deep Throat’ in the Watergate scandal, where he said to investigative reporter Bob Woodward, ‘If you want to know what’s going on, follow the money.’ And it’s true, we do it again and again and you do eventually find out what’s going on.

The other key issue is accountability – I find in my training of foreign journalists that often accountability is a hard word to translate. Some people think it translates to responsibility, but it’s more about balancing the books. It goes back to the idea of power: whoever you are, are you using the power you have in an accountable way?

For more information

http://www.icij.org

Editor’s note

The Center for Public Integrity, the parent organization of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, joined forces with the investigative journalism unit of the Huffington Post, making CPI the largest investigative journalism newsroom in the US. See New York Times article, 19 October 2010 http://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/19/business/media/19nonprofit.html?src=busln

Comments (0)