When UCL Professor Sarah Hawkes founded Global Health 50/50, she and co-founder Kent Buse were interested in understanding how the global health system performed against its professed commitments to gender equity. Hawkes wasn’t surprised to find that there is a lot of work to be done in that area – but looking at gender equity also proved to be a route to understanding how inequity of all kinds plays out across the system.

Professor Sarah Hawkes

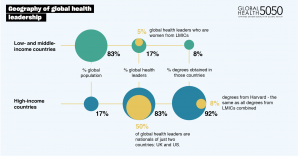

The data Global Health 50/50 collected in their 2020 report drives home these disparities. The leadership of global health organisations is overwhelmingly male and 50 per cent of leaders of these ‘global’ organisations are nationals of just two countries, the UK and the US. Moreover, in excess of 90 per cent of global health leaders are educated in high-income countries – eight per cent at Harvard alone, the same as were educated in all low- and middle-income countries combined.

As part of our current focus on global health philanthropy, Alliance magazine sat down with Sarah Hawkes to discuss the gaps identified by GH5050, how Covid-19 has reshaped the global health field, and what she hopes philanthropy will heed from their research.

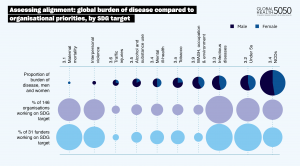

Elika Roohi: One of the gaps your research identifies is that global health funding doesn’t match the Sustainable Development Goals. What’s happening here?

Sarah Hawkes: So, in our research, we’ve seen these big gaps, and we kind of intuitively knew that the big gaps were going to be there. Because what we could see on the ground was that there was a lot more activity on issues like dealing with maternal health or child health than dealing with non-communicable diseases. And it’s not to say that we think that organisations shouldn’t be working on maternal and child health, of course. They absolutely should. But we also know that the profile of diseases has changed, and that even for the poorest countries, the biggest killers are now the non-communicable diseases. Yet really very few organisations in global health are paying attention to the non-communicable diseases; let alone paying attention to the risk factors that drive non-communicable diseases – for example excess consumption of food high in sugar, salt and fats. And so, we systematically set out in our research to capture that in terms of the SDG 3 commitments.

You can’t have a situation whereby you vaccinate only one country on earth… I think most other people absolutely realise that essentially none of us are safe until all of us are safe. That’s the nature not just of how infection spreads, but of what it means to be part of global humanity.

Our analysis revealed that the global health system is really still focused on an MDG [Millennium Development Goal] agenda, and it has not yet really substantively moved toward covering the broader spectrum of health issues that the SDG agenda covers. This includes addressing these NCD which, in more recent years, have become some of the biggest killers across poor and rich countries alike but remain fairly absent from the priorities of global health organisations. And you know it sounds a bit niche doesn’t it? Why worry about MDGs versus SDGs? And you know you could say, ‘Well is it a bad thing? You know, here we’re in the midst of an infectious global pandemic.’ But what we very clearly have seen with Covid is that actually it goes hand in hand with the epidemic of the non-communicable diseases, and populations are vulnerable to much more severe outcomes of Covid when they are suffering from NCDs or exposed to their risk factors.

To draw some parallels – something that comes up a lot in the climate funding space, which like global health is an incredibly broad area with striking gaps, is that certain aspects of climate action get really political and then to fund them becomes a political statement and then that becomes a barrier to philanthropic funding. Can you talk about how politicisation influences health funding?

Yes, I think as the report shows, what gets funded is driven by history, it’s driven by framing, it’s driven by notions of who is vulnerable and who is deserving. Not to put it too bluntly, but it’s a lot easier to raise sympathy for a young mother with a child than to raise sympathy for a young man who’s out of work and is smoking. They fit with our stereotypes about who’s deserving and who’s not deserving. I think the global health system has fallen into that as much as anybody has.

What we very clearly have seen with Covid is that actually it goes hand in hand with the epidemic of the non-communicable diseases, and populations are vulnerable to much more severe outcomes of Covid when they are suffering from NCDs or exposed to their risk factors.

But I think the gaps also speak to some of the problems being set up as solvable by health systems, rather than creating the conditions in which people can live their best and healthiest lives, which is the foundation of public health. So instead, so many global health organisations are focusing entirely on how you treat people once they’re sick. And I suspect that’s actually where there’s a lot of overlap with the climate issues – that it’s a lot easier to think about technological solutions to carbon capture than to think about how you change your entire way of living and being.

Another thing that was highlighted in the report is the power imbalance that there is in the global health architecture of the world. What are ways philanthropy can help decolonise the global health structures and make it more diverse?

It all depends on how radical you want to go. There are some very practical things that could be done, like ensuring that the organisations funders support actually have policies, practices, and programmes in place to ensure the principles of equality, diversity, and inclusion are played out in practice. Because philanthropy has financial power, so they’ve got the power to make change happen in their grant recipients. They can actually catalyse and foster and sustain change in the organisations that they fund, and it’s not too difficult to imagine that philanthropy could use that as a very strong mechanism for holding the grant recipients to account for change. In the long-term you could think about moving all those headquarters to be in places that are more representative of the global population. I think that you could talk about short-term and long-term strategies that the philanthropic sector can be part of. But the easiest is to ensure that they are fostering change in their grant recipient organisations.

Something your report asserts is that ‘the field of global health has long been a beacon for global solidarity’, and I’m wondering how much you think that’s been tested this year when it comes to Covid?

I would certainly stand by the notion that global health is about global solidarity. I think if the pandemic has taught us one thing, it’s that countries can’t solve this by themselves. This is not about individual nation states, and to be really honest with you, it never has been about individual nation states. If you look at the history of where the notion of some level of international cooperation came from between states around disease, it dates back to the 1500s.

So, has all this blown out of the water that you need global solidarity? No. At the end of the day, despite everything, I am still an eternal optimist that actually Covid-19 has highlighted to us that we need global solidarity even more. You can’t have a situation whereby you vaccinate only one country on earth. I don’t think any of us really think that that is the solution for the 21st century given that we trade and travel. I think most other people absolutely realise that essentially none of us are safe until all of us are safe. That’s the nature not just of how infection spreads, but of what it means to be part of global humanity.

Elika Roohi is Digital Editor at Alliance.

Comments (0)