Why should philanthropists fund the arts? Some have argued that as art is of lesser importance than basics like food, shelter, health and so forth, there is no justification for funding art until world hunger is solved. How then can one justify spending on so-called high arts? Can the arts be seen as effective tools to bring about personal and social change? Is art transformative? Our subject for this Alliance special feature is philanthropy’s attitudes to and role in funding ‘arts and social change’.

This special issue on arts funding was originally proposed by the Working Group on Philanthropy for Social Justice and Peace (PSJP). They commissioned Moukhtar Kocache to do a scoping study which emerged with the title: Framing the Discourse, Advancing the Work: Philanthropy at the nexus of peace and social justice and arts and culture. Kocache’s work made it clear that there is a dynamic intellectual debate about arts, culture and social justice among international grantmakers and artists and therefore an appetite to see some of the issues discussed more widely.

In looking at the issues and inviting contributors we wanted to confront head on some of the received wisdoms, opinions and contradictions we have both encountered on the subject. Philanthropic funding for the arts provokes strong views; few are lukewarm or neutral. We are grateful to our contributors for joining us in the effort to stir things up and then to calm them down.

Art is not simple

Some artists see their work as entirely about social change. This is true of many of the so-called high arts as well as the community and participative arts. For others art is pure at the point of creation and need not have social or political content or drive. Many people, including funders, draw a sharp distinction between the art that a professional artist makes, which may well intentionally stimulate social change, and the art that people without training or particularly developed talent make for their own purposes. Yet the art of protest or affirmation on a street gable may be as powerful as, if more ephemeral than, Picasso’s Guernica. And then there are those who believe that funding art at all is a frivolity while there is so much poverty in the world.

What should foundations do? Should they fund artists to create the art they want to make because artists are intrinsically valuable to society? Should they fund the places where art is made and displayed to make it universally available? Should they fund only work that outwardly promotes social change?

Given this complexity, what should foundations do? Should they fund artists to create the art they want to make because artists are intrinsically valuable to society? Should they fund the places where art is made and displayed to make it universally available? Should they fund only work that outwardly promotes social change? What about quality: does it matter if some community art that makes change is of lower quality (whatever that means)?

We want this issue of Alliance to be a debate about art and philanthropy. And we have been determined to show that this debate is global; the same arguments happen everywhere and many of the same observations apply.

Issues of language and definition

Is art the same as culture? People warned us about issues of language: what about culture in the broader context where arts, crafts and sociology collide? Others thought perhaps philanthropists needed a schema illustrating different ways in which the arts and artists collide and collude: for example, arts for self-realization, arts for provocation, instrumental arts at the service of social justice, art for its own intrinsic value … We decided to pay our readers the compliment of not trying to unscramble these questions; they are important but not essential for philanthropists in considering their policies towards arts funding. As for the schema, we thought it might be amusing to do but that we would end up arguing about categories rather than ideas or inspiring practice.

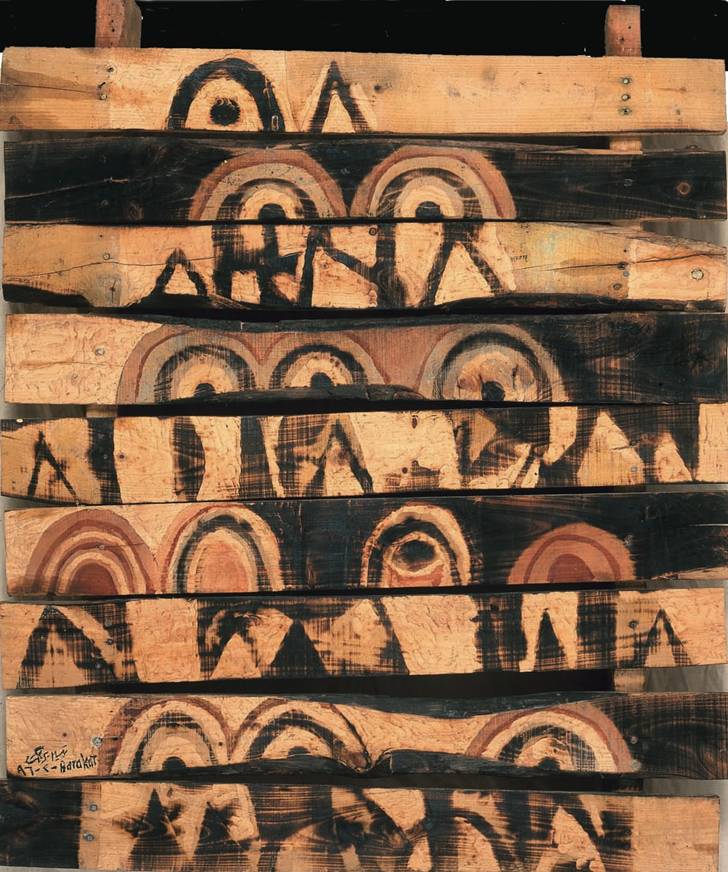

Palestinian artist Tayseer Barakat: Fire and Wood – ‘The return to the beginning … beginning of pray, love, speech, dance, the beginning of everything.’

What we are clear about is that there is no single cultural model to which everyone must aspire and no support in this special issue for arts that are thrust upon people because someone else decides what is good for us. One of us in a previous life as an evangelical public sector arts funder was reminded by a wiser man that there must also be freedom from the arts!

Putting Maslow to bed

One of the strongest oppositions people in the arts encounter when arguing in favour of philanthropic funding is the Maslow argument. As Barry Knight puts it: ‘How could something essentially transcendental be relevant to something so practical?’ Influential psychologist Abraham Maslow (1908-70) is widely held to have asserted that, in the hierarchy of human needs, arts and culture are of lesser importance than underpinning basics like food, shelter and health. Of course there is some truth in this. But superficial interpretation of Maslow’s argument has given many philanthropists permission to say that, simplistically, until world hunger is solved, they cannot justify funding art.

Even Maslow did not believe this so it is surprising that, despite evidence, the argument hangs around like a bore at a party. Katherine Watson, in her article, reframes the debate beautifully: ‘The answer lies not in placing art and culture in a balance with the urgent questions of our times, but in recognizing that it is truly an integral ingredient of the solution.’

Sarah Mukasa also argues strongly for the role of arts in the African Women’s Development Fund’s work in promoting women’s rights, while Santosh Samal shows how the significantly oppressed and underrated Dalits of India embrace literature, theatre and expressive crafts to make bold statements about cultural identity and the strength of their community.

The power of the arts and artists

If anyone doubts the power of art then a glance at a daily newspaper should offer some pause for thought. From the cancellation and obstruction of ‘El-Fan Midan’ (Art is a Square) in Cairo to the farcical 30 December police raid on Moscow’s independent theatre company Teatr.doc and the tragic events in Paris in January this year, there is usually evidence somewhere in newsprint that even the highest political figures believe art to be powerful. As the Wilson Center’s Blair Ruble puts it: ‘the mystery is why does Vladimir Putin’s government fear a minuscule drama company operating from a Moscow basement?’[1]

Why do dictators lock up the poets first? We asked some of our contributors to address the question of the power of the arts and culture, especially in places of unrest and where civil and human rights are a central concern. Case studies from HIVOS as a funder and the Irish Human Rights Film Festival as a recipient show how both artists and funders prize the contribution that cultural organizations make to promoting attitudinal change and disseminating messages about rights, especially where fundamental rights are questioned or withheld.

These contributors accept the argument that change comes about not just through information, evidence and persuasion but also through empathy. And few things can help attain emotional engagement better than theatre, film and story-telling. Several of our case studies show how the encapsulation of thoughts and feelings into a form that can reach into the hearts and minds of many challenges the status quo and encourages citizens to think for themselves. Sometimes this is robust and argumentative but more often the arts deliver ideas more subtly, not by preaching but by showing and sharing emotion.

So why would philanthropists not take advantage of such power? If social change is the goal then it must come from the ground up, as Katherine Watson reminds us: ‘Art and culture is essential for building open, democratic and inclusive societies … Change begins with people. Ideas flourish at a local level and then scale up and out.’

Artist Mike van Graan from South Africa argues: ‘Freedom of creative expression is often made subject to political and economic interests. It is against this backdrop that philanthropy in support of the arts and of artists is necessary to promote and defend independent artistic expression and distribution.’

An act of faith?

For their survey article Andrew Milner and Caroline Hartnell asked a selection of foundations and artists from around the world why philanthropists should support the arts. The answers are fascinating: a broad consensus emerges about the intrinsic value of the arts in expressing who we are, extending our boundaries, formulating our aspirations. None of our contributors resorts to the simplistic old belief that ‘art is good for you’.

India Foundation for the Arts grantee Ashavari Majumdar performing ‘Surpanakha – An experiment in Kathak’, at the India Habitat Centre. Majumdar offered a fresh view of Surpanakha, a much reviled character in the Ramayana.

Many of our contributors are happy to acknowledge that the arts can be used instrumentally but they emphasize that such reductionism does no favours to philanthropy, communities or artists. Barry Knight picks up the point: ‘… an assessment [of the value of art] should depend on the essential meaning of art itself, rather than on the attachment of a contingent purpose given to it by social activists. In other words, the value of art needs to be determined by its essence.’

Our survey respondents hold that it is axiomatic that arts and culture are central to our lives and that we would all be diminished by the absence of creativity. Funder Omar al Qattan voices the thoughts of several of them when he says: ‘Art is part of culture and culture is that wider universe containing what we see and hear, smell and eat, renege and accept, analyse and consume, and hate and delight in every day.’ He goes further; in his view philanthropists not only may but actually should fund the arts, particularly where the state cannot or will not do so.

We believe – and our contributors appear to support us – that funding the arts is such a rich seam that philanthropists are spoiled for choice. It is a good use of philanthropy to support the arts with or without explicit social purpose. And sensible philanthropy also invests in artists and the arts infrastructure that helps them thrive.

Philanthropy and access for all

Much philanthropic funding goes into projects that introduce people to cultural experiences they might not otherwise get the chance to enjoy. Will Miller tells us how and why the Wallace Foundation is investing $40 million to help arts organizations build and retain audiences from a wide social spectrum.

But Miller also talks about how drawing together all kinds of people – not just those seen as disadvantaged – to enjoy and be stimulated by artistic endeavour provides a fundamental social good: ‘Not every philanthropic act has to carry the full weight of all possible social benefits. Because the arts provide private value as well as public value, I think they can be, but they don’t have to be, about social change.’

We believe that funding the arts is such a rich seam that philanthropists are spoiled for choice. It is a good use of philanthropy to support the arts with or without explicit social purpose. And sensible philanthropy also invests in artists and the arts infrastructure that helps them thrive.

We do not wish, in arguing the merits of all varieties of arts funding, to pretend that everything philanthropists are doing for the arts is the best it could be. The US National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy in Fusing Arts, Culture and Social Change by Holly Sidford (2011) takes American philanthropy to task for skewing its (then) $2.3 billion annual arts funding towards elite institutions for elite consumers. But Sidford does not want an either/or stance. She and the grantmakers who supported the publication argue for thoughtfulness and awareness in grantmaking, for considering and understanding all the consequences of a grant to an arts body and trying to make sure that new and unfamiliar arts and minority communities also benefit.

Philanthropists can of course influence how great institutions use their money. John Nickson asked arts leaders from what might be thought ‘elite’ institutions in the UK about the effects of philanthropic funds on their work. As the Royal Opera House’s Alex Beard says: ‘philanthropists are active in helping us to change the way we work and to change the lives of others.’ Welcoming the collaborative attitude of philanthropists, Beard and others like him willingly embrace the opportunity to expand audiences and participants.

Supporting artists to be artists

No craftsperson would neglect their tools and so it must be with those who want to use arts as willing tools in the pursuit of social justice. Katherine Watson of the European Cultural Foundation is just one funder who advocates supporting cultural managers to share ideas and good practice across international boundaries. The Wallace Foundation’s programme to help 25 arts organizations with their audience development programmes will help build the underlying capacity of the organizations so that by attracting more audiences from a wider demographic they can fulfil their social purpose while building economic resilience. They will also share their knowledge and help others to learn good techniques and approaches to audience expansion.

Activist artists themselves are playing their part by sharing their experiences and helping each other across international borders. Many readers will be familiar with PEN International, funded by numerous philanthropists to campaign for human rights, chiefly freedom of expression through literature and media. Fewer will know of Germany’s Artist Organisations International – ‘over 20 representatives of organizations founded by artists whose work confronts today’s crises in politics, economy, education, immigration and ecology’.

From a series of photos by Eduardo Soteras Jalil called ‘Masafer. Life in the Interstice’, a project about the life of cave-dwelling communities in Palestine’s South Hebron Hills; supported by A M Qattan Foundation.

Proving it all

Both of us and many of our contributors can cite examples of lives transformed by exposure to or participation in arts projects. Yet artists in the survey article note that funders are sometimes deterred by the difficulty of measuring and attributing results for arts projects. Contemporary grantmakers need confidence in the efficacy and efficiency of the work they fund. So can we prove that the arts are effective agents of personal and social change? And can we show that they are at least as good as any other means? Speaking as a funder, arts project evaluations can be irritating: they are littered with confirmation bias; they tend to lack any base data with which to measure change; qualitative measures abound (and can be good) but for data geeks there is little to see.

If that last set of faults sounds familiar, it may be because the same criticisms are regularly thrown at other evaluations. Michelle Coffey of the Lambent Foundation highlights some of the challenges facing arts funders seeking to develop appropriate metrics.

Contemporary grantmakers need confidence in the efficacy and efficiency of the work they fund. So can we prove that the arts are effective agents of personal and social change?

Adrian Ellis tackles this problem from another angle, castigating the specious economic outcome studies that artists and arts organizations are forced to create to justify their subventions. He points us towards The Gifts of the Muse, Kevin McCarthy’s 2004 report for the Rand Corporation, which shows how the question of evaluation and value has to be unpacked and only then does it make sense. McCarthy does an excellent job of showing how you can measure if you know which indicators are right for certain contexts and which are not. So you can, for example, demonstrate health or education or crime reduction outcomes arising from arts input. But importantly McCarthy and his co-authors also tell us: ‘People are drawn to the arts not for their instrumental effects, but because the arts can provide them with meaning and with a distinctive type of pleasure and emotional stimulation. We contend not only that these intrinsic effects are satisfying in themselves, but that many of them can lead to the development of individual capacities and community cohesiveness that are of benefit to the public sphere.’[2]

So the answer to the questions we posed ourselves about proof is, effectively, yes, but you have to do a bit of work to make sure you ask the right questions, count the right things and approach the project with an open and honest mind.

You are allowed to change your mind!

The hearts of arts supporters fell when Bill Gates denounced funding of the arts by philanthropists as ‘immoral’, citing moral philosopher Peter Singer this time instead of Maslow, as Adrian Ellis tells us in his article. But recently the New York Times reported that ‘the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation is embarking on an online campaign using art to encourage immunization’.

In fact GAVI, the worldwide immunization programme funded by Gates among others, is creating a wonderful partnership between artists and scientists to promote the development and use of vaccines. The website http://artofsavingalife.com is well worth a visit. Look at Christoph Neimann’s animated story about keeping vaccines at the right temperature and you are guaranteed to remember the key points far better than if you simply read an article about it.From the Lascar cave paintings to wartime community singing to puppet shows in Syrian refugee camps in Turkey, people have used arts to talk about themselves, to communicate to others and to air difficult subjects, even while themselves struggling for survival.

We know of other philanthropists and their employees who would not describe themselves as arts funders but who have decided, like Sara Llewellin of Barrow Cadbury Trust, that ‘(if) an arts medium can contribute to our goal, we are open to that’. For some this involved a change of heart and a willingness to recognize the qualities and special abilities of arts projects that so many respondents to our survey pick out.

***

From the Lascar cave paintings to wartime community singing to puppet shows in Syrian refugee camps in Turkey, people have used arts to talk about themselves, to communicate to others and to air difficult subjects, even while themselves struggling for survival. They have also enjoyed themselves. It should be no surprise that the right to a cultural life is enshrined in the UN Declaration of Human Rights (Article 27): people have voted for it with their dancing feet, their singing voices and their wielded paint brushes.

We hope you enjoy reading this special issue – yes ‘enjoy’, because arts and enjoyment go hand in hand. If you are already a committed arts funder we would like you to find more good and bolstering ideas and arguments to support and test your position. If you are a doubtful philanthropist we would like to stimulate you to ask more, better questions and to follow some of the leads our contributors have for you. We do not expect you to read this magazine and fling up your hands in surrender while simultaneously planning a major contribution to building a new gallery in an area of cultural deprivation. We would much rather you had a good think about where and how and when working with artists might help you realize your overall goals. And then think about how you might support artists to be there for you when you need them.

The guest editors for this Alliance special feature:

Hania Aswad is executive director of Naseej Foundation and a member of the ‘Philanthropy for Social Justice and Peace’ Working Group. Over the past 20 years, she has worked in a number of countries and across the Arab region as a social justice and arts practitioner and advocate. She was formerly a dancer and has recently developed a passion for photography. Email haswad@naseej-cyd.org

Fiona Ellis began working life in the theatre before moving into the philanthropic world, first at the Gulbenkian Foundation and subsequently as director of the Northern Rock Foundation, then one of the UK’s largest independent grantmakers. Now she administers a small foundation and writes scripts for an award-winning performance company. Email fiona@fionaellis.co.uk.

Lead image: Minimum Monument, urban intervention performed specifically for the Latin America Memorial, São Paulo, Brazil. Photo by Néle Azevedo http://www.neleazevedo.com.br

Comments (0)