How do foundations navigate changing government priorities and policies? How do they challenge social injustice without provoking government intervention? A group of foundation leaders gathered at the Bosch Foundation’s recent global philanthropy conference in Berlin outlined pragmatic approaches to working with governments.

If an organization a foundation supports uncovers systemic injustice, for which the government is responsible, and speaks publicly about it, relations between government and foundations break down. This seems to be true across the globe. There are ‘safe’ and ‘edgy’ issues, and no matter where a foundation works, if it takes on the edgier issues, it is likely to risk government displeasure, observes Barry Gaberman (an independent philanthropy professional).

Speaking safely about social problems

Chinese foundations have learned to use pragmatic language to effectively advocate for marginalized people, says Tao Ze of the China Foundation Center. In 2012, a group of foundations invested a total of $6 million into feeding rural children. After the foundations highlighted children’s needs, the government promised to invest $6 billion in the programme.

Learning to use ‘safe’ words and projects can help ensure that advocacy work does not prompt government reprisals.

The nutrition programme is a safe area so long as foundations don’t compare malnutrition among rural children in China with hunger in other countries, he says. Similarly, philanthropists rarely work in politics, especially if the philanthropy is international, he observes, and a foundation can support women’s issues as long they are presented as a concrete problem and not as a human-rights issue.

In challenging environments, foundations use more guarded language. In such situations, debate is more likely to centre on investment and social enterprise than on civil society, because investment is a less risky topic. CSOs advocating for fighting poverty in Saudi Arabia focus on a sufficiency line, rather than a poverty line, for example.

‘CSOs fighting poverty in Saudi Arabia focus on a sufficiency line, rather than a poverty line.’

US non-profits adapt their language to the market as well. For instance, one environmental group discusses climate change in its approach to European donors but focuses on the effects, for example, floods, in its approach to some US donors. In this way, they avoid politically charged language in the US. Social justice is another issue that many non-profits have avoided. It is one reason why the Ford Foundation’s recent focus on inequality has generated such discussion, says Gregory Witkowski, from the Lilly Family School of Philanthropy at Indiana University.

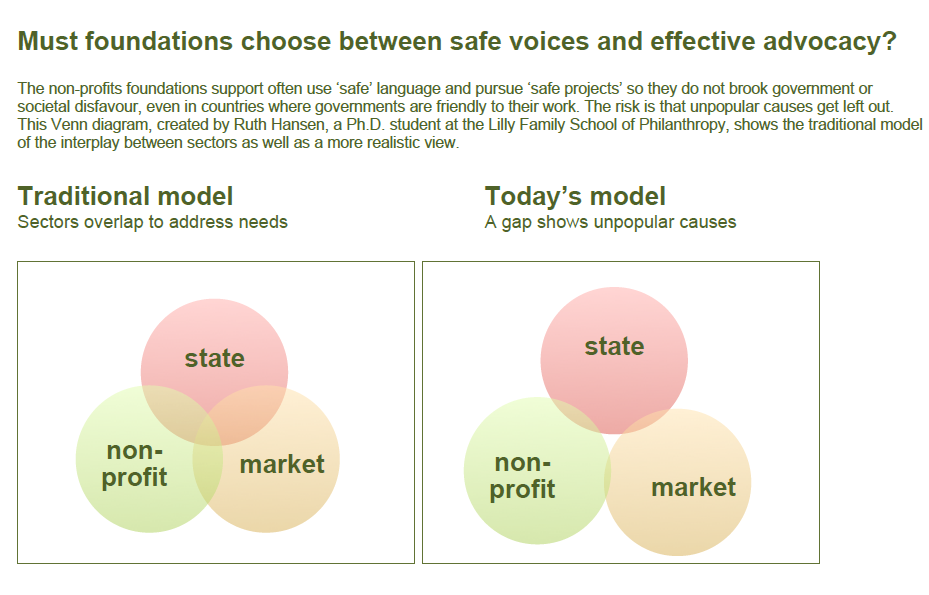

The increasing use of technical, non-political language in the sector creates the risk of marginalizing groups who do not fall within its sphere and even jeopardizing their existence. There is a danger that these groups will be left out by all three sectors.

Working in safe areas

Beyond the use of pragmatic language, philanthropists have adapted programmes to avoid brooking government opposition. Foundations in Gulf States — an area that emphasizes compliance, end up sticking with programmes that are ‘not too risky’, says Natasha Matic of the King Khalid Foundation. Royal foundations have a bit more independence, because they do not have to report to the government but still, for the most part, they stay within the realm of ‘acceptable’ work – such as sponsoring orphanages, education and health programmes.

Even when working in safe areas, people have to build effective relationships with people inside ministries and departments. When a minister or an official is replaced, the process of cultivating a relationship has to begin again.

The best way to encourage successful initiatives by governments and others is through a combination of operating a successful project to address a problem, creating a strong evidence base, and advocacy, says Volker Then of the Centre for Social Investment at Heidelberg University. Increasingly, big foundations are collaborating for advocacy purposes, forming advocacy coalitions.

Despite difficulties in relationships with government, Marcos Kisil (Institute for the Development of Social Investment in Brazil) says he remains optimistic. In Brazil, the sector has brought in new money to address social problems, and governments and corporations are hearing its voice. ‘We are a sector that can bring innovation,’ he says. ‘We are a new voice, lobbying for something new.’

Andrew Milner is the associate editor of Alliance. Email am@andrewmilner.free‑online.co.uk.

Comment

The Indian government is asking for funders and corporations to give directly to the government rather than to NGOs. Those NGOs that question the government about its policies and practices, collaborate with like-minded foreign organizations, or receive funding from agencies and philanthropists outside the country can be perceived as a threat to national security.

Government has taken recourse to ‘interpretations’ of existing rules to derecognise thousands of registered NGOs, demand explanations about the past and current work of hundreds more, and stop donors from continuing to fund many others. Organizations receiving funding from foreign sources, in particular, are being questioned, investigated, and often suspended on grounds of technicalities.

A closer look at the profile of some of those organizations that are being questioned – both large and medium sized, indigenous ones, and India chapters of foreign charities – reveals a distinction. Organizations involved in mass public movements or human rights, or who have taken activist-driven positions questioning the government and corporations, are under the scanner. Many of these organizations experience a culture of threats and fear.

In this shrinking space for civil society in India, organizations are committed to talking to the government and being heard by the state. Often, one friendly face in government agencies strengthens our position to pursue the social justice agenda. It is also helpful at times like these to keep the noise levels low and wait for the turbulence to pass.

The Indian voluntary sector has always battled against historical fault lines – corruption, fragmentation and distrust. In a billion-plus country that boasts more than three million registered NGOs, these challenges scale up to humungous proportions.

The government has mostly treated the NGOs as a nuisance. But that has not excluded the state from regularly reaching out to NGOs for consultations, feedback on government services, and policy framing. Coalitions of NGOs also raise their voices of dissent to move the government to act against rights violations and social injustice. This has made the civil society in India a key platform for voicing public opinion. Now it’s a key platform for government restrictions.

Sumitra Mishra is India country director of IPartner India. Email sumitra.mishra@ipartnerindia.org

Comments (0)