Increasing levels of human rights funding and its changing priorities mirror developments on both the global and local level, as fascinating research by the Human Rights Funders Network and Candid shows

Our research maps the funding landscape for human rights and tracks changes in funding levels and priorities. Human Rights Funders Network and Candid (formerly Foundation Center and GuideStar) launched the Advancing Human Rights initiative in 2010, in partnership with Ariadne – European Funders for Social Change and Human Rights, and Prospera – International Network of Women’s Funds.

Funding for human rights reached $2.8 billion in 2016, an increase of 34 per cent from the previous year.

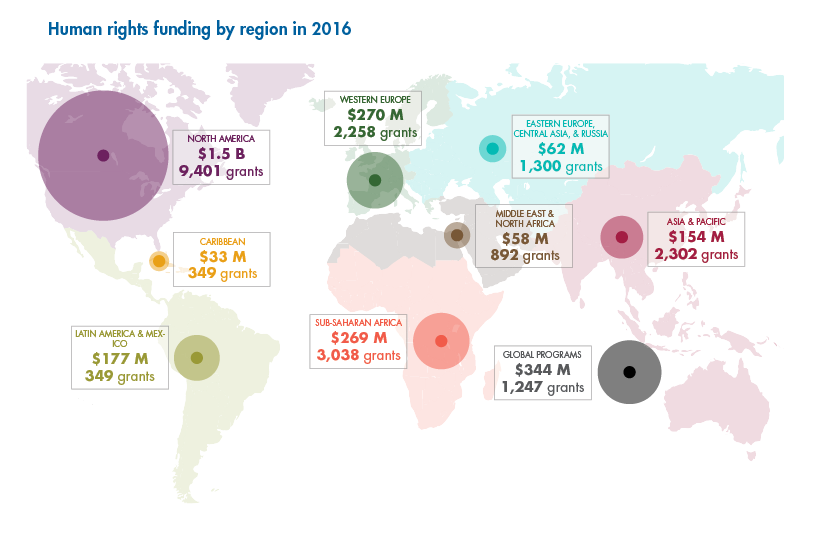

In 2016, the most recent year of available data, 785 funders based in 43 countries made 23,016 human rights grants to address the root causes of injustice and inequality and promote structural change. Five things stand out.

Human rights funding is increasing. We documented $2.8 billion of human rights funding, more than ever before, and saw a 34 per cent increase between 2015 and 2016 from funders that submitted grants data for both years.[1]

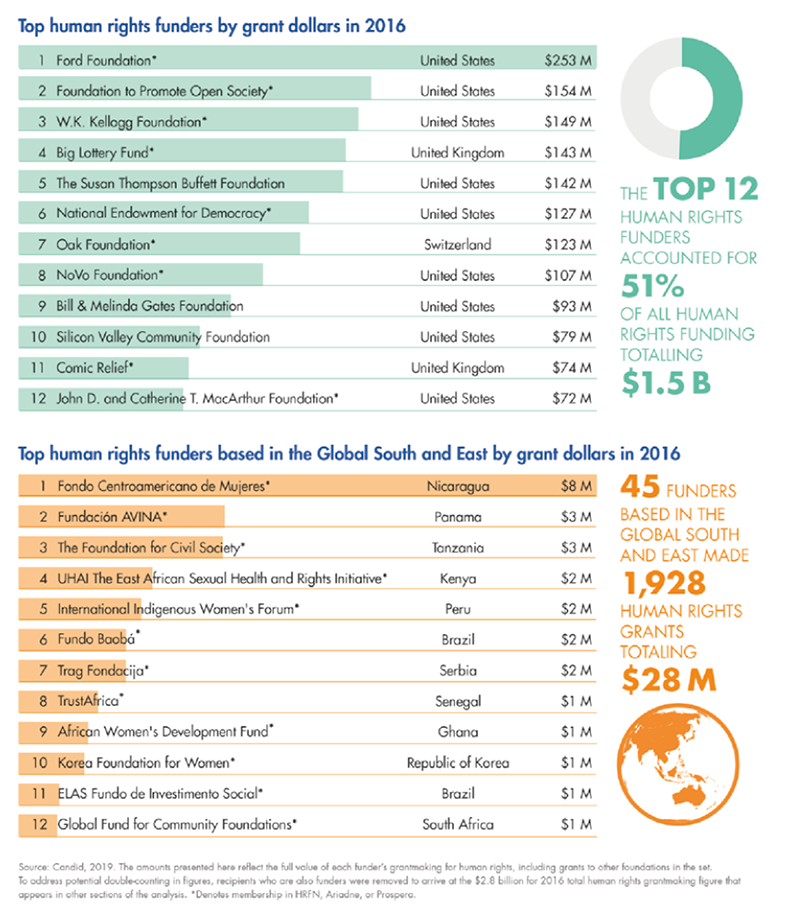

A handful of funders have considerable influence. The top 12 of the 785 human rights funders accounted for 51 per cent of total grant dollars.

Most human rights donors do not identify as such. Two-thirds of foundations that made human rights grants are not institutions that necessarily identify as ‘human rights funders’, but they awarded one or more grants that meet our definition. This offers an opportunity to explore intersections and potential collaboration between these foundations and self-identifying human rights funders.

Much of the money goes to non-local organisations. In four of eight world regions, the majority of grant dollars meant to benefit those regions were instead awarded to recipients who worked in those locations but were based in other places. In part, this is likely related to the requirement that US foundations must evaluate whether intended foreign grantees are the equivalent of a public charity, which may be excessively burdensome for smaller foundations. It may also indicate that some funders are opting to work through intermediaries with local knowledge. Notwithstanding the various reasons for this, the issue raises questions about trust in organisations based in the Global South and East that deserve further study. We also found that recipients based in North America are significantly more likely to receive flexible general support than recipients in other regions, which reinforces this concern.

Participation in donor networks could influence funding practice. Members of HRFN, Ariadne, and Prospera were three times more likely than other funders to specify target populations in their grants,[2] and seven times more likely to fund organisations based in the Global South and East. This underscores an opportunity to encourage the larger pool of human rights funders to more intentionally support marginalised communities and locally based organisations.

To read more about our findings, visit humanrightsfunding.org.

Rachel Thomas is director of research initiatives at the Human Rights Funders Network.

Email: rthomas@hrfn.org

Twitter: @hrfunders

Anna Koob is director of research at Candid.

Email: anna.koob@candid.org

Twitter: @CandidDotOrg

Footnotes

- ^ Year-to-year changes in grantmaking can be influenced by the actions of one or a few foundations, the authorisation of multi-year grants in a single year, a small number of very large grants, or a foundation submitting more detailed and comprehensive grants data. We should be cautious about drawing long-term conclusions about shifts in grantmaking based on single-year changes.

- ^ This is in some measure because members often submit their grants data to us directly, while we frequently secure non-member data through public reporting.

Comments (0)