In this special feature on community philanthropy, we propose a new paradigm called ‘durable development’. This involves shifting power closer to the ground, giving agency to local people and their organizations on the principle that they should have greater control of their own destinies. The growing field of community philanthropy has much to contribute towards such a paradigm shift because it marks a distinct break with many of the conventions – and resulting distortions – of mainstream development. The ‘three-legged stool’ of community philanthropy combines asset development, capacity building and the strengthening of trust between multiple local and external stakeholders. Durable development follows John Ruskin’s maxim – ‘when we build, let us think we build forever’.

In 2010, we wrote a report called Beyond the Poor Cousin? The emergence of community foundations as a new development paradigm. The essential message was contained within the title. Despite its potential and the emerging evidence base that supported it, community philanthropy was either unseen or ignored by the big players in development aid and institutional philanthropy. Local people mobilizing local resources for development processes was largely regarded as supportive of, but not as essential to, effective development – a niche or boutique feature of the development landscape, but a long way from being a retail, let alone a wholesale staple.

The rise of community philanthropy

How things change. Six years later and community philanthropy no longer languishes in the shadows. As the external environment for civil society and donor funding undergoes dramatic changes, community philanthropy and its emphasis on local resources and local accountability has assumed a new relevance as a central pillar of a framework for effective development shaped by new principles.

There is now a Global Alliance for Community Philanthropy, a Community Foundation Atlas, chairs in community philanthropy at two universities and recognition among key funders that the aid architecture needs to change. At the same time, the language of ‘localization’ among funders and International NGOs (INGOs) also suggests a growing focus on strategies that shift power closer to people on the receiving end of development.

As the external environment for civil society and donor funding undergoes dramatic changes, community philanthropy and its emphasis on local resources and local accountability has assumed a new relevance as a central pillar of a framework for effective development shaped by new principles.

This progress has been accompanied by the rapid growth of the community philanthropy field globally over the last two decades. The growth has been organic and hence somewhat messy and unorganized, characterized by the nuances of local context and by emerging community philanthropy practice and values. It has also marked a healthy loosening of tight definitional ties to the US community foundation model – signifying a shift from the close relationship of siblings to that of a larger extended family.

Although there is still work to be done to strengthen a common narrative that captures both the essence and diversity of the field, there is a new enthusiasm among different stakeholders to unite in pursuit of a shared purpose. The basis of the common narrative is the ‘three-legged stool’ framework of assets, capacities and trust, as identified by an analysis of data collected through the Global Fund for Community Foundation’s grantmaking. Applying 20 indicators measuring bonding, bridging and linking social capital to GFCF grant partners – which include a mix of community foundations, women’s funds, environmental funds, grassroots grantmakers and public foundations – shows that these three factors are of central importance.

This edition of Alliance coincides with the Global Summit on Community Philanthropy – an event that marks the coming of age of the field. The meeting will bring together 300 people from over 50 countries, including the community philanthropy field in all its diversity, a range of public and private funders, and others from the broader development space, to consider how we can shift the power and create durable development.

The end of aid?

The context of international aid is shifting. As Danny Sriskandarajah points out in his article, the days of rich Northern countries delivering large amounts of official development assistance (ODA) to poor countries in the global south are numbered.

This may be no bad thing. Only one per cent of official aid goes directly to the global south, with the remainder being passed through northern-based intermediaries. A similar pattern is found among foundations. So, while money flows to the South, power remains vested in the North.

As Jennifer Lentfer points out, such an approach does not work. For decades the money flows from the North have provided resources for development but have ignored, subsumed or done harm to already existing mechanisms for mutual accountability. Projects have come and gone, but have disappointed every time. Hilary Gilbert notes in her article drawing on work in Sinai: ‘…people the world over are tired of being told what to do by “experts” who don’t understand, tired of seeing money poured away.’

It is now clear that the idea of project-based sustainability is an illusion, merely fostering an elite of skilled proposal-writers and supporting an NGO sector that has been hard-wired to exist on a hand-to-mouth basis, with organizations crossing their fingers that the next grant will come in and always at the ready to adapt their work towards the latest donor interest. This has produced an NGO sector whose orientation is upwards and outwards towards their external donors, leaving them with weak local constituencies. In the meantime, local people who are marginalized stay marginalized. The result is 50 years of failed development projects.

Donors themselves are recognizing the need for change. Some practical examples of changes can be seen in USAID’s ‘Local Systems Framework’ and in the UK’s Big Lottery Fund’s vision of ‘People in the Lead’. In his article, David Jacobstein from USAID says: ‘There are many places where staff are experimenting with these ideas and our updated guidance provides a new opportunity for principles related to community philanthropy to be mainstreamed.’ The Global Alliance for Community Philanthropy is a group of diverse funders who are trying to get to grips with these issues by deepening their understanding of community philanthropy as a field and asking questions about how external donors can develop programmes and apply resources in ways that foster – rather than undermine – more bottom-up approaches.

Only one per cent of official aid goes directly to the global south, with the remainder being passed through northern-based intermediaries. A similar pattern is found among foundations. So, while money flows to the South, power remains vested in the North.

Lighting a candle

While donors get their act together, local people are not necessarily sitting on their hands. In her article, Larisa Avrorina describes how in southern Siberia, an area with no big business, no money, low incomes and a faded sense of community, a musical event sparked off collaborations between different organizations and resulted in the formation of a community foundation. ‘It’s like lighting a candle,’ she says.

Similar developments can be found in other contexts. In Latin America, Luz Aquilante describes how the Women’s Fund from the South recruits supporters for women’s rights work through direct person-to-person outreach on the streets of Argentina. Andrés Thompson describes how community philanthropy is modernizing the Latin American concept of philanthropy and its associations with beneficence, charity and social assistance from the church. In Palestine, Aisha Mansour describes how the Dalia Foundation has inverted the power pyramid in philanthropy by making grants the community wants through a participatory decision-making process with the community: difficult work, but deeply significant in a context where development aid has created a heightened sense of disempowerment and voicelessness among local communities.

Power matters because efforts to solve a problem only last while people with the problem take responsibility for it.

A new approach

Individually, these examples from Russia, Latin America and Palestine may seem like one-off feel-good stories. Collectively, however, they symbolize a new approach to development, sharing as they do the assumption that all communities possess assets, ideas and a readiness to engage. What tends often to be missing, however, is the ‘spark’ to make that happen. Similarly, they are all illustrations of what occurs when you choose to reach deep into communities and engage multiple views and voices through conversations, events and small grants to local initiatives.

Rather than working through a handful of strong professionally-managed NGOs to deliver programmes – which looks cost-effective on paper – community philanthropy organizations deliberately seek to build up multiple local groups around issues that affect them in a networked way that devolves resources (and so power) to the very local level. Rather than every member of the community having to subscribe to a single overarching vision or objective, this strategy allows community philanthropy organizations to engage with multiple different perspectives and to reach the most marginalized parts of the community, whose voices are often lost. As Wendy Richardson points out, this is a model of shared power described by one grant partner of the Global Fund for Community Foundations: ‘We don’t work on troubled youth, we work with troubled youth’. Such an approach builds capacity, it develops assets from within a community and – above all – it builds trust between different parts of a community.

Such durable development is in sharp contrast to the project-saturated mindset in which outcomes are measured within finite resources and timeframes and measured in a logframe. It is time for us to rid ourselves of the illusion that three-year projects using outside resources can unravel complex inequalities and system failure. Addressing such problems requires the patient creativity of people involved in the local systems to build what they want from resources they already have and what else they can muster. External resources must be applied in accord with local people’s plans, not according to a blueprint laid down in Washington or London.

Another important dimension of this development relates to the growing trend towards devolution and local self-governance, and the extent to which community philanthropy can be seen as a strategy for facilitating communities to take a more active role in local decision-making, particularly in contexts where local government itself lacks capacity. In Kenya, note Irũngũ Houghton and Constant Cap, there are growing calls by public interest campaigners to embrace strategies that involve the mobilization of both public and community resources to tackle systemic causes. The Kenya Community Development Foundation’s Pamoja4Change programme, as described by Caesar Ngule and Janet Mawiyoo, views resource mobilization by community-based organizations as a critical part of a process that strengthens communities’ ability to make claims on government to deliver services.

It’s all about power

Power is the key to durable development. Power matters because efforts to solve a problem only last while people with the problem take responsibility for it.

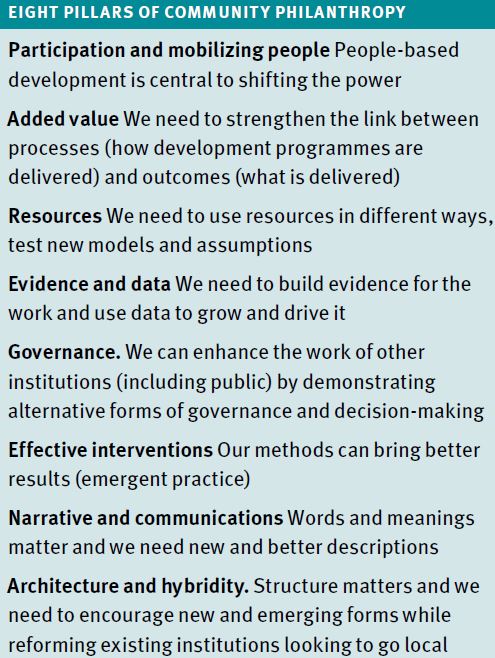

This is the topic of the Global Summit in Johannesburg. The preparations and follow-up to the summit are as important as the event itself. The purpose of the summit is succinctly described by Hilary Gilbert when she says ‘The Global Summit’s #ShiftThePower challenges donors to cut through discredited norms, take a deep breath and invest in something better.’ In preparing for the summit, we have identified eight pillars that people suggest for shifting the power.

Rather than working through a handful of strong professionally-managed NGOs to deliver programmes – which looks cost-effective on paper – community philanthropy organizations deliberately seek to build up multiple local groups around issues that affect them in a networked way that devolves resources (and so power) to the very local level.

Developing durable development

Developing durable development

So where do we go from here? Well, the first step is to recognize the new paradigm by capitalizing on trends that are already evident and to begin to explore possible opportunities for further development. One important starting point is the emerging field of community philanthropy organizations, diverse but bound by a shared essence, and grounded within their constituencies, which is gradually starting to realize the power of its collective voice.

Another starting point is among those development actors who are starting to look to the principles of community philanthropy as a strategy for strengthening the participation of people in decisions and the allocation of resources around issues that concern them. There is growing realization that local, participatory philanthropy is a critical piece of the new landscape for civil society, because it combines money as well as the dimension of horizontal accountability. As civil society globally sees increased restrictions on its ability to operate freely, including an increased criminalization of activism and an overall reduction of traditional sources of support, it offers new insights and strategies for local constituency building for issues of rights and social justice.

Once we have recognized the importance of this new paradigm, we can then move on to developing it. The question is how? Evidence from developing the field to date suggests that top-down plans and fixed blueprints should be avoided because to do this would itself be inimical to the paradigm.

Rather than a linear silver-bullet approach, a better way forward involves nurturing the ecosystem in which community philanthropy organizations operate. Many such organizations are small and fragile and the appropriate way of developing them is to support their development according to the rules and priorities they set themselves, rather than norms and standards set from outside.

We will now consider how this might work for the three main constituencies involved – the community philanthropy field, funders and international non-governmental organizations.

Community philanthropy field

It is important that community philanthropy organizations feel confident that their day-to-day efforts, which can at times seem messy and challenging, are part of a new paradigm that is holistic, organic, and fuelled by the energies of local people. It is also important to feel the power of a networked approach to development, looking for shape and structure without imposing it, and keeping the right balance between tangible and intangible results. For money to translate into good development, it needs other inputs, including trust, confidence, and a sense of agency.

While intuition, values and gut instinct are important in developing the work, it is also important to develop rational systems to deepen the evidence base for it. The field needs to develop better measures of its performance and to answer questions about the development field’s obsession with replicability and scalability – perhaps developing evidence-based answers derived from scaled up networks and measures of distributive leadership. Susan Wilkinson Maposa’s ‘horizontality gauge’ offers a new way of thinking about this. It is important to help external donors understand what the field is trying to do and how their support could help.

Rather than a linear silver-bullet approach, a better way forward involves nurturing the ecosystem in which community philanthropy organizations operate.

Donors

Donors need to ‘think jazz’ – be flexible, willing to improvise and get beyond self-imposed limitations. It is important to take time to understand the community philanthropy field and avoid assuming that donors’ own systems and structures should be projected onto local organizations. Bilateral donors need to get beyond their short-term view and accountability mechanisms and widen the development tools they have at their disposal. Perhaps they could take a long hard look at the balance between the need to get significant funds out of the door and the larger development imperatives based on principles of social justice, equity and democracy, and be prepared to retune their strategy. Private philanthropies – both international and domestic – can use the power of their long-term and flexible funding.

For bilateral donors in particular, who say that community philanthropy is new and unfamiliar, taking them beyond their comfort level, they should reflect on their common practice of creating ‘pooled funds’ or ‘re-granting intermediaries’. Although these are often called ‘foundations’ with local boards and other trappings of independence, they are often so only in name: in reality they tend to be mini-versions of the donors that established them, with systems and structures cut and pasted from the mother ship and with little investment in thinking through long-term sustainability and local ownership, which leaves such organizations vulnerable and fragile when the donor funding comes to an end.

International civil society, including INGOs

There is soul-searching to be done about the business model that has sustained ‘development’ since the term was first coined in 1949 by President Truman. Fundraising has been a rather one-dimensional tool to secure money in order to do the real work. This is unsustainable. NGOs have been existing in ways that we would never recommend to each other as people, hand-to-mouth, year-to-year, with no strategies for saving and a development environment that rewards spending out every last penny. Are these the NGOs – entirely dependent on external resources and so external power – that local people really want?

It is now imperative that international civil society organizations begin to think in more blended, integrated ways, where community philanthropy and local asset mobilization becomes part of a strategy for local constituency building and community development. In this way the divide between ‘donor’ and ‘beneficiary’ can be broken down in favour of the idea of ‘co-investment’ where different actors bring different strengths and needs to the table in a more reciprocal way. And there are still uncomfortable conversations that need to be had by and within INGOs about their real willingness to give up power.

Donors need to ‘think jazz’ – be flexible, willing to improvise and get beyond self-imposed limitations.

Conclusion

This brings us straight back to power and the discussion to be held at the Global Summit on Community Philanthropy. Our starting point for the summit is that six years ago, community philanthropy was the proverbial tree that fell in the forest: invisible, unheard because big development was not there to hear it. Now, community philanthropy is turning into an oak with ambitions, to borrow a phrase from the civil rights movement, to ‘stand tall’[1].

In conclusion, we can think of no better comment than that made by Sean Lowrie in his piece on rethinking humanitarian aid when he comments that the original goal of development aid was not to hold power but to develop people. He says: ‘It is time to stop fretting about control and think instead about maximising impact. The first humanitarians sought neither power nor control, but impact. They measured this in lives saved and suffering spared – and now so should we, their successors.’

Jenny Hodgson is director, Global Fund for Community Foundations. Email jenny@globalfundcf.org

Barry Knight is adviser, Global Fund for Community Foundations. Email barryknight@cranehouse.eu

Footnotes

- ^ Standing Tall is a poem by James McKenzie about Martin Luther King.

Comments (0)