The practice of community giving has experienced mixed fortunes amid profound national developments

In 2004, the Ford Foundation funded a study to understand the relationship between philanthropy and social justice in predominantly Muslim societies, including Egypt and Turkey. This article provides a perspective on what has changed in these two countries since the initial study was conducted, and what the future might hold.

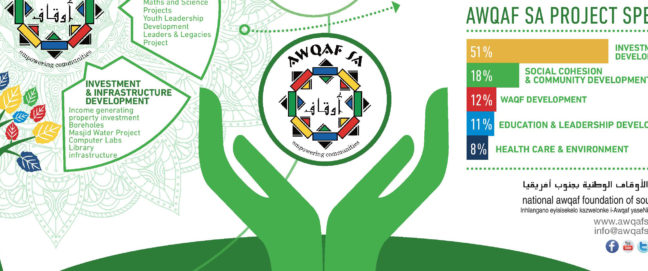

The Islamic world has always seen philanthropy as a feature of peoples’ everyday lives: waqf or vakıf, the rough Arabic and Turkish translation of an endowment, is an old tradition. Until the emergence of the modern state in Egypt and Turkey in the 19th century, this structure channelled private wealth for public goods and services as diverse as public schools, universities, public hospitals, public baths and saunas, public water-fountains, soup kitchens and much more. Waqfs still exist in the form of endowed lands and enormous accumulated wealth but are no longer autonomously managed by appointed comptrollers or nuzzar. Rather they are directed by the state, in the form of the Minister of Awqaf or Habous in Egypt and the General Directorate of Foundations in Turkey, which oversee both ‘old’ (Ottoman era) and ‘new’ (Republican era) foundations.

Egypt: Philanthropic giving defies economic climate

Participatory rapid appraisal in Cairo.

Philanthropy has flourished in recent years, even as economic conditions have deteriorated and the governments of the Arab and Islamic states, including Egypt, have struggled to meet the economic and social challenges before them. A 2004 study funded by the Ford Foundation was the first quantified assessment of philanthropy in Egypt and in other countries in the region. A key finding was that the per capita share of philanthropy in Egypt ($14) was greater than that of overseas economic development aid. Over 62 per cent of Egyptians, rich and poor, donated annually. Religious giving gave expression to compassion or takaful which reflected the idea of rights-based philanthropy. However, because of the harsh economic climate, most of the money given was on an ad hoc and personal basis and lacked a sustainable institutional character. It went largely to the giver’s immediate circle – family members, neighbours and close friends. Again, religious influence promoted the concept of ‘al aqraboun awla belma’rouf’ – ‘kindred are more worthy of your giving’.

The study of philanthropy meant that concepts like waqf and philanthropy itself started to appear in the media, which accelerated public awareness of traditional and sustainable philanthropic institutions.

In 2007, two major developments occurred in Egypt as a consequence of the study. The first was the establishment of the country’s first community foundation, which revives waqf as a concept and promotes social justice philanthropy through its programmes. The creation of Waqfeyat al Maadi Community Foundation (WMCF) directly affected policy by opening the door for successful advocacy, which in turn led to the addition of a new constitutional clause that obliges the government to revive and modernize the waqf concept. The other direct result was the establishment of a centre for philanthropy at the American University in Cairo (the Gerhart Center for Philanthropy and Social Engagement) to promote local philanthropy and its study.

Young PRA participants at WMCF.

Philanthropy has developed significantly since the original study. The beginning of the 21st century saw the creation of mega-hospitals, subsidized by fundraising campaigns in the media, in addition to the emergence of a couple of large charitable associations headed by the grand Mufti of Egypt, the highest official of religious law in a Muslim country. The study of philanthropy meant that concepts like waqf and philanthropy itself started to appear in the media, which accelerated public awareness of traditional and sustainable philanthropic institutions. Online donations and giving hotline numbers became a trend, which led to a more institutional giving. Prior to 2011, this giving was still directed to service provision, not to social justice philanthropy, but following the ‘Arab Spring’ of that year, civil society came to prominence with concepts like social justice shaping its thinking and actions. Civil society organizations (CSOs) promoting civic and human rights started to play a more prominent role. This was however followed by a backlash from government and the media alongside reports of corruption among high profile CSOs, with those working in human rights and receiving foreign funding attracting particularly negative attention. These incidents have shaken the confidence of the public in institutionalized giving and acted as a brake on philanthropic donations.

A recent Participatory Rapid Appraisal (PRA) on philanthropy in southern Cairo by WMCF revealed a distrust which has prevented individual philanthropists from donating to big institutions and showed a growing preference to donate individually. Although some CSOs, like Waqfeyat al Maadi, offer the prospect of channelling philanthropic impulses into social ventures and in support of social entrepreneurs, the wider public still prefers to make personal donations to relieve visible needs.

Turkey: Levels of public trust are a key factor

Many of the dynamics and challenges facing philanthropy in Egypt are similar to the situation in Turkey. Low levels of public trust (overall and in CSOs), a tendency to give directly to those from similar backgrounds rather than to organized groups, and a focus on helping the poor resonate loudly within the Turkish context.

Following a 2004 study by TUSEV, the umbrella body for foundations in Turkey, a more extensive survey was undertaken by the organization in 2015. For the most part, no significant changes were observed. Yet taking a deeper look into the results, there are three areas in which significant changes have occurred relating to the perception and practice of philanthropy as a form of civic engagement.

‘Religious giving’ (frequency and amount) appears to have decreased:sadaqa from 79 to 68 per cent and zakat from 40 to 28 per cent.

Turkey’s mosques attract high levels of giving. Credit: David Stanley

The ‘motivation for philanthropy’ was perceived to be primarily religious (32.5 per cent), exactly the same as in 2004. However, a notable decrease was observed in giving motivated by social traditions and norms, from 26.3 per cent to 20.4 per cent.

‘Religious giving’ (frequency and amount) appears to have decreased: sadaqa from 79 to 68 per cent and zakat from 40 to 28 per cent. Economic hardship was cited as the main reason, which is unsurprising given the significant economic downturn in 2015. Mosques and other religious activities appear to have captured the highest percentage of donations as compared to other organized civic groups, at 13.7 per cent, with almost no change since 2004.

The perception that the state has responsibility to help the poor has undergone a significant increase – up from 28 per cent to 44 per cent. Less significant changes were observed in those who saw it as the role of the wealthy (up from 30 per cent to 31 per cent) and of all citizens (up from 19 per cent to 21 per cent) to help the poor. As for the perception of CSO influence, there was a significant drop from 64 per cent to 48 per cent, indicating that the public may have lost trust in CSOs’ role in society.

Over the last 10 years, the Turkish government has increased capacity and spending on basic services, such as universal health, which may have contributed to this changing perception of responsibility. A decline in the enabling environment since the 2013 Gezi protests, along with increased terror attacks, an attempted coup in 2016 and two years of a state of emergency may have led some of the public to be less trustful of CSOs. Data from a recent monitoring report by TUSEV also supports this trend, citing a significant decline in overall CSO participation rates.

As in Egypt, Turkey too has seen the development of philanthropy infrastructure over the last decade. This infrastructure includes Turkey’s first community foundation, charity runs and online platforms which have mobilized many new donors. However, economic, political and social tensions appear to have affected individual giving patterns as well as engagement in more organized philanthropy.

Marwa El-Daly is founder and chairperson of Waqfeyat al Maadi Community Foundation and managing partner of MERSIC.

Email mdaly@aucegypt.edu

Twitter @Marwa.ElDaly

Filiz Bikmen is founding director of Esas Social Investments in Turkey and an international philanthropy adviser.

Email filiz.bikmen@esassosyal.org

Twitter @FilizBikmen

Comments (0)