The need for thoughtful, holistic, democratic stewardship of natural resources has never been more critical. Community philanthropy can play a big part in the management of large-scale natural resources, but it faces challenges in doing so. What can be done to help it overcome obstacles and to amplify its power in this role?

Two community foundations, the Newmont Ahafo Development Foundation (NADeF) in Ghana and a newly forming trust in Malawi’s Shire River Basin, provide insight into both the challenges and opportunities for communities to build collective ownership of assets and ensure appropriate, democratic governance of natural resources. A look at three key areas – decision-making, small donor investing and sustainability planning – illustrates how community philanthropy could succeed at a larger scale.

Unlike institutions funded and managed by corporations and transferred to communities later, in these examples communities are principal decision-makers from the outset. NADeF, with a US$13 million endowment from gold revenue, was established through an agreement between Newmont Mining and ten communities affected by mining activities in the Brong-Ahafo region. Six of the nine board members are elected community representatives; the elected board chair is a community member nominated by Newmont. A social responsibility forum of more than 40 people represents all stakeholders and approves NADeF’s budget and development strategy. Community-led sustainability committees identify funding priorities. The NADeF board is considering a special investment fund for past scholarship recipients and a donor-advised fund for Ghanaians abroad. While the amount of revenue may be small, the act of investing instils a sense of shared ownership.

Of course, the sheer size of the budget can create competition for resources even in communities with a history of successful collaboration. Grants for cross-cutting projects and multi-community projects can be an effective antidote to this problem by uniting people around a common objective and strengthening trust.

Through an agreement between the US and Malawian governments, the Mount Mulanje Conservation Trust (MMCT) in Malawi has convened 24 stakeholders, ranging from grassroots leaders to elected officials, to design a grantmaking institution to manage conservation of Malawi’s largest reservoir. The trust will be supervised by an elected board of individual ratepayers, smallholder farmers, corporate water users, government officials and institutional donors.

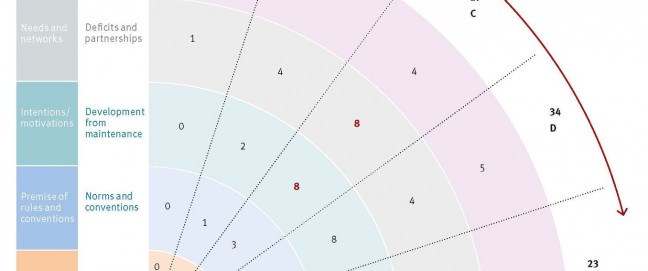

Community Engagement at Afrisipakrom in the Tano North District, 2015. Picture credit: Sabina Adu-Wusu

Even with governance structures founded on community decision-making and meaningful participation, community-managed foundations established with a large investment from one source risk being unduly influenced by that investor. One option for the Shire River Basin Trust, which received approximately US$5 million from the Millennium Challenge Corporation, is to designate revenue from a small ecosystems service fee from individual households and farmers as a joint community investment.

Of course, the sheer size of the budget can create competition for resources even in communities with a history of successful collaboration. Grants for cross-cutting projects and multi-community projects can be an effective antidote to this problem by uniting people around a common objective and strengthening trust. NADeF has experimented with two successful small grants for education in all ten communities, and many stakeholders want the grant programme to expand.

Power-sharing and trust-building practices help communities manage not only financial resources but natural resources as well. In Malawi, stakeholders are having vigorous discussions about whether sustaining the watershed means investing only in direct conservation or also supporting other community priorities. A large community-managed trust provides structure and visibility for these conversations, making them more consequential than they would be if they were only happening among elites or in isolated communities.

To gain traction in large-scale asset management, community philanthropy can benefit from strategic partnerships. Conventional environmental trusts are a logical fit: they could raise the profile and credibility of this model, and the model could increase the trusts’ relevance and benefit for communities. Community philanthropy is also a philosophical cousin of environmental and human rights. Organizations working in these areas can strengthen community foundations’ capacity to advocate for community self-determination and negotiate equitable agreements.

These ideas are just a start. We are glimpsing the potential of community philanthropy in the management of large-scale assets, but we must invest in and support more of these efforts to understand the true power of the model.

Mary Fifield is principal of Kaleidoscope Consulting and former director of Amazon Partnerships Foundation. Email mary@meetkaleidoscope.com

Comments (0)