‘We have a convening power and a brand name power, in the sense that we are accepted in Belgium as a foundation that is working for the public interest.’

Belgium’s King Baudouin Foundation (KBF) is a large foundation in a small country. This potentially gives it an extremely powerful position. How does the foundation deal with this, Caroline Hartnell asked KBF managing director Luc Tayart de Borms.

Within Belgium, the  Foundation is a very powerful organization. At the same time, you address the issue of sharing power in some very explicit ways. Could you tell us how and why you devised them?

Foundation is a very powerful organization. At the same time, you address the issue of sharing power in some very explicit ways. Could you tell us how and why you devised them?

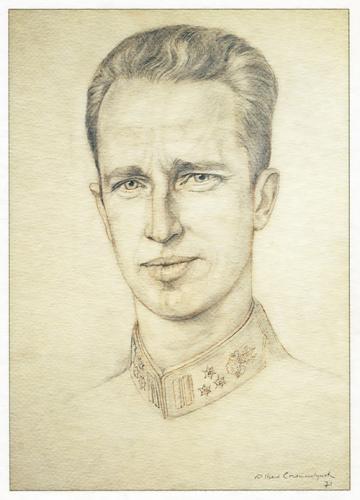

The history of the foundation is a curious one. We are not a foundation created by one individual or corporation or family. We were in a way created to serve the public interest, the interests of Belgian society. Parliament created the foundation and gave it to the king (pictured in a study for a portrait by Albert Crommelynck, 1971 − gift of the artist to the King Baudouin Foundation), who had been on the throne for 25 years, and the king gave it back to the nation as an independent foundation. So from the beginning the governing structure was one where the board tried to be a mirror of Belgian society. I think that is quite unique. I think we can be very proud of the way we do things, but partly the explanation is the way we were created.

What power does KBF have?

We have a convening power and a brand name power, if I can call it that, in the sense that we are accepted in Belgium, and more and more also in Europe, as a foundation that is working for the public interest. We are always involving different stakeholders, so the power of execution or implementation of a strategy doesn’t rest with either the board or the staff alone. Last year we had 1,700 people involved in expert groups, selection committees and so on.

Is this for defining programmes or implementing them and selecting grantees?

The board sets the overall strategy. To give an example, the board decided that one of the things we want to do is to change attitudes towards dementia in society. That’s difficult. It’s easier to change policies than to change attitudes in my opinion. So that’s quite an ambitious goal and we won’t achieve it with one tool; we will do it with grants, research, giving policy advice, etc. And around every project that is part of that overall objective, we have a group of people – experts who guide our staff on how best to do it. If we say we’re going to support local authorities around policies on dementia, then we will have a separate selection committee. In reframing Alzheimer’s, which is more research driven, we will have a group from the academic field looking at it. The board receives a mid-term report to see what is happening, but they will not intervene to say who will get grants or subcontractors, or in the framing at the academic level; all of that is delegated to committees where our staff are in fact the project managers.

So the committees both work out the detail of the implementation and select the grantees and partners?

Yes, if there are grants. So it doesn’t give a scandalous amount of power to the programme officers, which is often, in my opinion, the case. That often means they push their own paradigm. If you have a group around the programme which represents different paradigms and try to get a consensus, you will have a bigger consensus with society than if a programme officer with a very specific idea on how things should be done tries to push that through. If you have a selection committee with different people, they will come from different backgrounds, they will learn from what’s happening in the field, and they will immediately become owners of your project and investors in it, so you widen the pool of changemakers around the area you are working on and the ideas you can draw on. You have of course peer review in scientific research, but this is our approach to the overall management and implementation of our projects.

Don’t you also have a sort of ‘neglected issues’ scouting group?

That’s the Listening Network, which is part of our social justice work. We also have two other very specific groups. One consists of doctors, general practitioners, who we ask to bring us the challenges their jobs throw up, and we have a similar group of notaries. But the broadest of the three is the Listening Network.

Does that feed into the board’s strategy setting?

Does that feed into the board’s strategy setting?

Under the heading of social justice, the board actually gives a kind of ‘blank cheque’: they leave it to a committee to identify the methodology and the projects. This has to be approved by the management team, but the board doesn’t want to see it back. It just stipulates that the Listening Network should not attack problems that are too big; it should look at small issues. For example, the Listening Network will never work on the problem of social housing overall, though it might identify particular aspects of it to work on. (Pictured: Migrants find themselves in a particularly vulnerable situation in case of divorce. Often isolated from families and friends and not speaking the language of the host country, they don’t know where to go for support – one problem thrown up by the Listening Network. Picture credit Dubova)

What informs strategic reviews at the foundation?

It’s a combination of top-down and bottom-up. The committees that provide guidance around a certain project, dementia for instance, will advise our staff and management team. So that’s the bottom-up element.

But you also need a top-down element. If you ask experts, you will always continue in certain fields, because there is always something to do. It’s very difficult for an expert to say ‘let’s drop this issue’. So sometimes the board steps in and decides. It happened, for example, a few years ago on architectural heritage, where the board said: ‘Listen, you have done your bit over 15 years, you have achieved a lot, the regional governments are in place, you have created civil society organizations. Now we don’t feel you have any more to add, so we think you should not continue that.’ So we switched to health issues, which was new to us and where we thought we could be useful.

Why is power sharing so important?

It is important for different reasons. The best way to have impact is to create ownership in many different places around a certain subject, and to do that you have to involve key players in the field. Before we start a project, we do a mapping exercise to classify stakeholders and their function in achieving the impact in question. So we have a kind of intellectual discipline; we’re always thinking of the functions of stakeholders in relation to the theory of change.

From the management point of view, it is a cheap way to bring in expertise. And because we have a good brand name, people are ready to work for us for free. We don’t want experts in the foundation, we want intelligent people. The expertise we buy in or get free so my colleagues can concentrate more on the theory of change and on project management. Also, it keeps our staff numbers relatively small.

Finally, this power sharing gives you a lot of credibility with policymakers because they know that what you are saying is driven by different types of people, even people with different political opinions. Some politicians say we are the only place left in Belgium that works for public benefit.

You talked about the power of programme officers. What sort of power do you have as managing director?

I only have power in relation to strategy. My job is to make sure that my colleagues are playing the game correctly. The management team meets every two weeks and my colleagues propose external teams for this or that project. I am responsible for ensuring that we have balanced teams – not only a balance of grassroots, academic and corporate opinion, but an ideological balance too. So my job is to make sure that public benefit is followed.

As I mentioned, there is bottom-up and top-down input into our strategy, and I have the power to influence the agenda in both ways. I can propose things to the board, who decide in the end. But the management team, including me, can say, ‘we’re going to work further on that, that and that’ and we exclude certain things and stop certain things. But we don’t really have power in relation to implementation.

Given the breadth of interests KBF is negotiating all the time, how do you avoid working to the lowest common denominator? What enables you to take risks? Is there a role for leadership here?

There are at least three ways to avoid falling into the trap of the lowest common denominator and to go for enough risk taking. The first is the framing of the issue, the challenge: the way the societal challenge is put to the expert groups will of course influence the kinds of answer you will get. Second is the composition of the groups. Two elements are key here: the personality and vision of the chair and trying to make sure that you have at least one maverick in each group.

Both these points bring us to the issue of leadership by the management team. Framing the issue and endorsing the composition of committees is their task and they are key elements in the success of a project.

How do you see the power of foundations relative to other players in society?

We have the freedom to think long term, to think of the public benefit. We can put things on the agenda and work on them as a ‘submarine’ for years, without stockholders or voters preventing us. In today’s society I think the ability to think long term is a huge luxury, but at the same time it’s a kind of power, because who else can permit themselves to do that? We also have convening power, being able to use different methods to achieve an impact.

But we have to be modest because we don’t have the money – compared to government – and we don’t have the political legitimacy to implement, at the end of the day. We have to accept our catalytic role, and after the chemical process has taken place, you’re gone. You can’t say ‘See what we did!’ because if you do, in future they will not follow you. Someone, maybe an American president, once said, ‘It is incredible what you can achieve if you don’t care who gets the credit.’[1] That’s our power, I think. That’s why we have the power to influence policies – because we are not seen as a threat by politicians; we cannot be accused of being biased. This is also quite boring. It means the media are not always interested because we are consensus driven.

Do you see examples of the power of philanthropy being misused?

I think in some foundations individual programme officers are simply pushing their own political ideas, and for me that’s a kind of misuse. If you do that, you should be with a civil society organization or an advocacy group – make it clear what you stand for. Sometimes I think foundations hide themselves behind the trustworthy name of foundation to push a political agenda. In the US it’s clear, in Europe perhaps less clear – but I think you can also put political labels on a lot of the foundations in Europe.

Not us! The only label I’m willing to put on us is that we see ourselves as progressive and we are not for the status quo. For our staff, that means they have to be engaged, but they cannot be militants. This is difficult for some people and I don’t blame them. Society needs militants, but they do not have a place in this foundation.

1 The quotation is generally attributed to President Harry S Truman, most commonly under the form ‘It is amazing what you can accomplish if you do not care who gets the credit.’

For more information

http://www.kbs-frb.be

Contact Luc Tayart de Borms at TAYART.L@Kbs-frb.be

Comments (0)