Individual, family and corporate philanthropy are often seen as three distinct types of philanthropy, with different motivations for giving. But how different are they in their actual approach to giving? How differently do they address social issues? A discussion on trends in individual, family and corporate philanthropy at the Berlin meeting on Perspectives on Arab and Global Philanthropy suggested that a lack of trust in NGOs, a desire for direct engagement and a disinclination to support difficult issues are common trends. We asked the Berlin panellists whether these trends are changing in the younger generation.

A lack of trust in NGOs as intermediaries

Mistrust of NGOs was a common theme at the Berlin meeting. NGOs may be seen as agents of government (because they sometimes run government programmes) or as a conduit for funds from abroad or simply as inefficient – or even corrupt. Russians in general continue to be reluctant to give to NGOs, preferring to give directly to people in need, for example, for healthcare problems. In Spain, many endowed foundations are turning into operating foundations, preferring to act directly and operate their own programmes rather than doing so through NGOs – a trend that is discernible in corporate philanthropy in South Africa, too.

The China Foundation Center uses data sources to build trust between foundations and NGOs to work on issues like women’s rights.

But things are improving. The China Foundation Center (CFC) is using the creation of data sources as a means of bringing foundations and NGOs together to create mutual trust. In addition, according to Tao Ze of the CFC, as the younger generation become more familiar with the idea of grantmaking, they are becoming more interested in talking to NGOs and understanding what they do. In Russia, the last few years have seen the rise of voluntary groups around a particular issue; this gives them an air of legitimacy and they are finding favour with corporate donors.

What about the next generation? We need to distinguish between retail donors and major donors, says Maria Chertok of CAF Russia. The former give more to NGOs in general and are more likely to get engaged as volunteers – in Russia those who give or engage in any type of activism tend to be much younger than in the UK, for example. But when it comes to major donors, there is no ‘previous generation’: they all are relatively young and self-made. ‘And I would say that they carry all the prejudices of society including mistrust of NGOs and lack of understanding of what they are and what value they create,’ says Chertok.

But the softening towards NGOs is not seen everywhere. Marcos Kisil of IDIS in Brazil says there is no evidence that the younger generation feels more confidence in NGOs. While observing that data on this is lacking, Rosa Gallego of the Spanish Association of Foundations mentions that ‘new ways of donating, such as crowdfunding – often to raise money for a cause put forward by an individual rather than an NGO – are very much supported by young people’.

A desire for direct engagement

Another trend that seems to be common among individual, family and corporate philanthropy is a desire for direct engagement and an increasing reluctance to work through intermediaries. This is partly due to mistrust of NGOs, which are the main intermediaries through which philanthropy carries out its work. But there are other factors. New donors often assume that the skills that made them successful in business will work for social change. While some in Berlin expressed scepticism about this, others favoured applying business acumen to philanthropy.

What about the next generation? Are they more likely to be looking for direct engagement and focused on results? ‘Definitely yes,’ says Rosa Gallego. ‘No doubt,’ says Marcos Kisil. ‘If donors work through NGOs that they are part of, it is a way of controlling the use of resources and directing them to the results that they are looking for to transform society.’

‘Among high net worth individuals in South Africa, we are seeing a small trend towards a business-minded approach in newer philanthropists,’ says independent consultant Halima Mahomed, ‘particularly those who are bridging their individual and corporate philanthropy roles rather than seeing them as distinct. But this is not as yet the norm.’

Firoz Ladak of Edmond de Rothschild Foundations agrees that recent trends indicate that a new generation of philanthropists wants to be more hands-on. ‘Many feel that their entrepreneurial success in business can be applied to a more impactful change, for instance in the field of social entrepreneurship.’ But he sees another factor behind the wish for direct engagement: ‘sometimes it stems from the fact that philanthropists wish to implement new ideas and solutions that do not yet exist’.

A disinclination to support difficult issues

The reluctance to support difficult issues often arises from a fear of putting donors at odds with government. Many wealthy families in emerging and developing economies shy away from the idea of supporting social justice issues, partly because of the political implications and partly because of their own vested interests. In South Africa, both corporate donors and high net worth individuals (HNWIs) tend to play safe when it comes to the issues supported. In Russia, the most common motivation for philanthropy is not to change but to help. In Brazil, it was suggested, it is safer to implement public policies, then if the policies are bad, the government is to blame. In China, foundations avoid anything ‘political’. For example, you can talk about women’s issues as long as you treat them as a concrete problem not as a human rights issue.

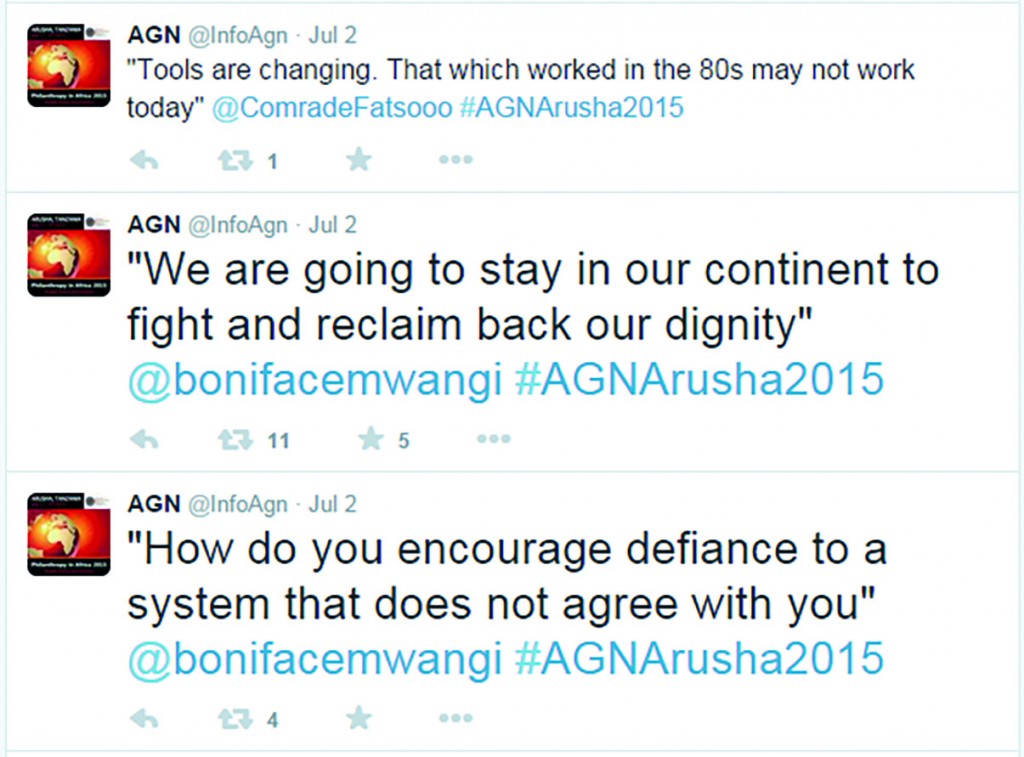

What about the younger generation? Are they more committed to tackling root causes? Halima Mahomed discerns a ‘small trend’ among more prominent companies and next gen HNWIs in South Africa. However, ‘if the AGN [African Grantmakers Network] conference twitter feed on the youth session is anything to go by, ordinary individual next gen givers are calling for a radical transformation of how philanthropy is done and calling outright for root causes to be addressed head-on.’

Maria Chertok is not sure but feels this may develop. ‘The idea of root causes is not exactly widespread in Russia,’ she says. ‘But the young are more likely to look at issues in all their complexity, including elements of advocacy, for example. And they tend to learn from their experience and change their strategies, so maybe someday this will evolve.’

In Brazil, on the other hand, Marcos Kisil says that the desire ‘to accelerate concrete results and impacts’ means that a new generation of donors don’t tend to want to tackle root causes or look at issues in all their complexity. Rather, ‘they prefer to work with situations that do not require a long period of time to show impact’.

In Spain, says Rosa Gallego, ‘everything is profoundly affected by the economic situation, which has led the sector to have to attend basic needs (ie strong growth of food banks) rather than root causes’.

Caroline Hartnell is the founding editor of Alliance.

Email caroline@alliancemagazine.org

Comments (0)