Investments made by governmental and philanthropic donors in healthcare systems around the world too often reinforce arrangements that favour private interests over public provision

In March, Indian author and activist Arundhati Roy observed that, ‘historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next.’

For those of us working in philanthropy, the pandemic provides an opportunity to reflect on the complicated political and economic role we play in global health. This issue of Alliance considers what we can do to rebuild faith in the ‘public’ in public health and restore more balance to our political and economic systems.

Too much philanthropy?

Consider the following.

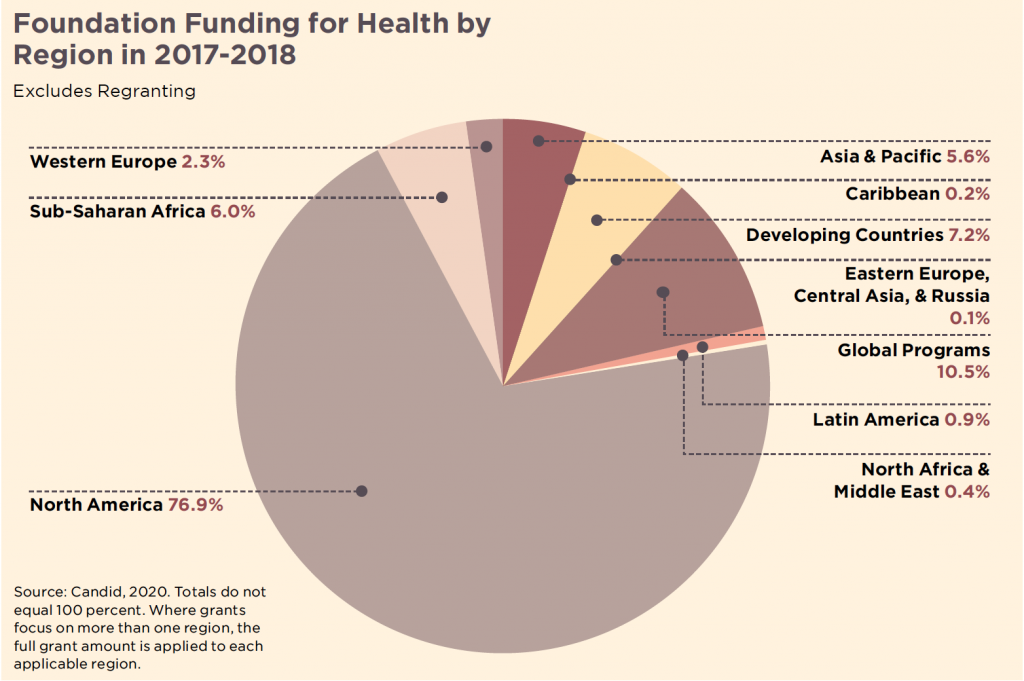

- In 2017 and 2018, the top 100 private foundations and grantmakers spent over $46 billion on health – representing 23 per cent of all private giving, according to Candid data.

- Governmental and philanthropic donors provide over 40 per cent of all health spending in nine African countries.

- Sustainable Development Goal 3 on Good Health and Wellbeing requires countries with poor healthcare systems to spend at least 8.6 per cent of GDP on healthcare by 2030 yet most lower income countries are spending less than half of this amount.

These data show the pre-eminence of private foundations and donor governments – each with their own geopolitical interest or niche funding area – in the health policy-making of lower income nations. This is compounded by a focus of most donors on disease-specific outcomes rather than on broader health systems. The result? The fragmentation of health systems in low- and middle-income countries, and the illusion that donors have health covered, letting governments off the hook for the provision of basic health services. It also breeds corruption, as health is increasingly seen as a cash cow for government coffers, a profit centre for national and multinational hospital chains and a market opportunity for insurance and pharmaceutical companies.

The impact of private money also risks creating an accountability ‘black box’. Susan Erikson and Leigh Johnson’s article discusses the implications of profit-driven pandemic financing models – notably so-called ‘pandemic bonds’ – operating with little or no public oversight. The inability to see how healthcare systems are being financed is particularly damaging because it undermines the efforts of citizens to advocate for alternative healthcare models.

Donors’ support continues to be focused on the use of market-driven models, including for Covid-19. For example, at a side event at the recent UN General Assembly, Bill Gates announced an unprecedented partnership between 15 pharmaceutical companies and the Gates Foundation to expand global access to Covid-19 diagnostics, therapeutics and vaccines.

Health advocates have long documented the ways in which some of the pharmaceutical companies involved in this partnership have massively profited from drugs primarily developed with public money. These pharma companies are poised to profit once again in the race for a Covid vaccine, following the influx of public money from the US and European countries for advance purchases of vaccines for their own countries. While Bill Gates himself acknowledges that so-called ‘vaccine nationalism’ is a problem, his solution, in this case, is to forge a partnership with pharmaceutical companies to lower the prices and dictate the terms of access for lower income countries. Not only are these arrangements typically made without public oversight, but they do not change the intellectual property rules, and monopoly pricing, which prevent more systemic change over the longer term.

As we witness the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on black, brown, and Indigenous bodies, donors need an enduring focus on racism as a public health crisis in its own right.

The high prices of drugs, including Covid vaccines, cannot be justified by the high costs incurred by companies for research and development, when so much of the R&D is funded with public funds. The US government has invested $19 billion in the race for the vaccine[1] for example. Indeed, this partnership of pharmaceutical companies seems to ignore calls from political leaders across the globe to consider a Covid vaccine as a public good – from the president of Costa Rica calling for all global stakeholders to share Covid-19 knowledge, data and intellectual property, to the presidents of South Africa and Ghana calling for a People’s Vaccine available to all, free of charge for all. The important work of the Gates Foundation has been evident since the pandemic began, from support of the WHO to efforts to build vaccine manufacturing capacity in lower income countries. But it should not be for private foundations and pharmaceutical companies to set the terms for access to vaccines for lower income countries in a pandemic. That is the role of national governments, held accountable by civil society, and member state-driven multilateral institutions.

Pharmaceutical companies have massively profited from drugs primarily developed with public money. Photo: Adam Niescioruk

So where do private actors derive the legitimacy to intervene in global and national health governance?

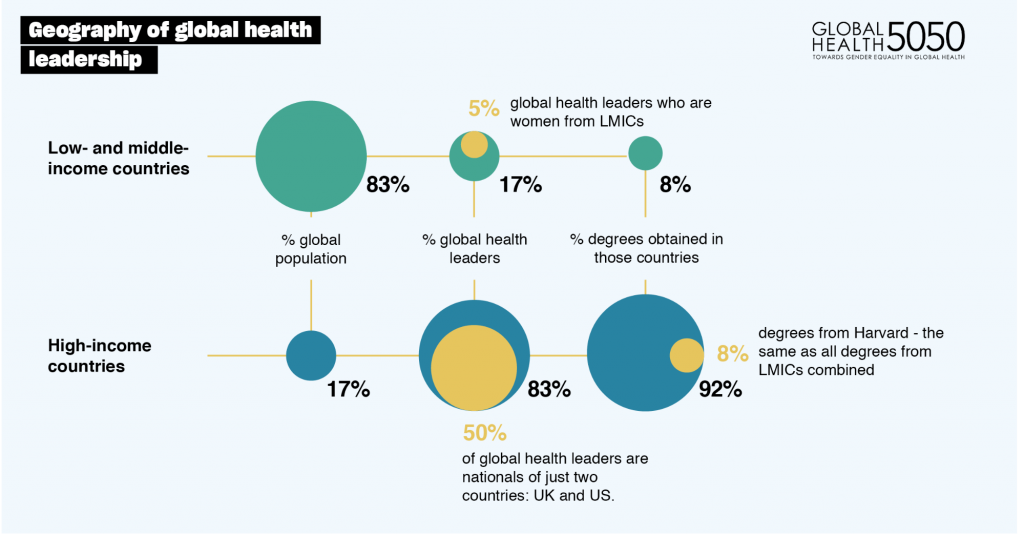

A recent critique by Rwandan activist Paula Akugizibwe is that private philanthropy and public donors, often working together with companies, are reinforcing an extractive global health architecture in which they (not states and citizens) create the conditions for access to health and ignore the massive impacts of inequality on public health. Akugizibwe argues that policy prescriptions implicitly and explicitly attached to funding from donors even influences the ways countries allocate their own domestic resources for health, complicating the very idea of national sovereignty in health decision-making.

Private donors, ourselves included, cannot afford to ignore this critique.

In our view, funders should not subsidise the health budgets of lower-income countries – in the case of Kenya, 23 per cent is provided by external donors – nor should we use our funding to influence the behaviour of states, where we have no legitimate role.

Global health philanthropy: not enough

Consider with us instead an affirmative role for global health philanthropy in a world that will undoubtedly be shaped by this pandemic for decades to come. The fact that health systems from the US to Ecuador buckled under the onslaught of the pandemic, suggests an important role for philanthropy in supporting a transformative vision of universal healthcare. This vision resists the radical privatisation which compromised the US response to the pandemic, the politicisation against which WHO director-general Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus so powerfully and painfully cautions in this special feature and the exclusion of groups whose rights are denied by authoritarian states and fundamentalist movements proliferating around the globe.

Victory celebration after a successful court-case against the Ugandan government in August this year which resulted in the right to maternal health being enshrined in the country’s constitution. Photo: CEHURD

The politicisation of health

Health activist partners of our East Africa Foundation, OSIEA, have warned that philanthropic funding can act as a political analgesic. Instead of treating the source of pain, philanthropy offers temporary relief that disarms potential civic action to address a lack of domestic action on health. While a massive amount of philanthropic spending goes towards research and biomedical approaches to health, we need to see more funding for the kinds of efforts and organisations showcased in this issue of Alliance.

Solutions need to be local

One example of philanthropy adopting a citizen-centred approach involved relatively modest funding from three US foundations – Hewlett, Wellspring, and Open Society. These foundations supported a coalition of 40 Ugandan civil society organisations to take the Ugandan government to the Supreme Court over its failure to provide maternal health to its citizens. In August 2020, the court ruled in the petitioners’ favour, and the right to maternal health is now enshrined in the Ugandan constitution. Significantly, in the nine years the case took to make its way through the courts, the Ministry of Health has overhauled its reporting mechanisms for maternal deaths, and rates have dropped in certain districts as the government moved to demonstrate accountability for this failure. By contrast, donor governments and multilateral health financing organisations rely too heavily on international organisations to implement programmes on behalf of ‘beneficiaries’ in low-income countries. Salaries and indirect administrative and operational costs benefit consultants and staff from outside the country and the companies with which they have procurement arrangements. A recent report by amfAR, the Foundation for Aids Research, estimated that between 2007 and 2016, the US presidential initiative on Aids spent up to $4 billion on ‘indirect costs’ which did not go directly to programmes on the ground. The continued power of these multimillion-dollar contracting organisations is one of the most vivid remnants of a colonial global health system that is extracting resources rather than redistributing them. Risk-taking and flexible philanthropic dollars could be better spent elsewhere.

The examples throughout this issue of Alliance strongly suggest that we cannot play our proper role in helping to end health disparities without addressing economic inequality and racism.

A report from Uganda’s Institute for Social and Economic Rights provides another example of the problem. The report shows how a public-private partnership with USAID and the Government of Uganda, implemented by the international organisation ABT Associates, invested millions in a voucher programme to stimulate demand for maternal child health, which has not led to significant reductions in maternal deaths, especially for poor women.[2] In fact, the programme in Uganda has an explicit goal of subsidising private clinics to show their effectiveness in programme delivery, thereby undercutting efforts to roll out a publicly funded national health insurance programme.

Mind the gaps but do not fill them

Some argue that a sweet spot for global health donors is in securing access to health for populations whose rights are denied due to criminalisation, fundamentalism and intense social stigma. But donations in this area should be focused on dismantling the systems of oppression, not on creating unsustainable parallel health systems that perpetuate them. As Ban Ki-moon of The Elders cautions in his article on universal health coverage, ‘philanthropists and the sector can complement the state but they cannot replace it’.

There is scope for donors to build on the lasting and inspirational legacy of the global HIV response. That response brought action from governments and donors to address the disproportionate impact of public health failures on women, people who use drugs, migrants, sex workers and LGBTI people. But the philanthropy in the aftermath of Covid-19 should move well beyond the limited focus of the HIV movement on the ‘marginalised’. Instead, as we witness the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on black, brown, and Indigenous bodies, donors need an enduring focus on racism as a public health crisis in its own right.

The opportunities for reimagining philanthropic investments in global health which we have put forward are driven by an analysis of the ills of the legacy of colonialism in the global health system

We also see clear gaps but also opportunities when it comes to mental health and sexual and reproductive health programming. Each received just 6 per cent of philanthropic health funding in 2017 and 2018 according to Candid’s data – and both are areas where intense social stigma, criminalisation and institutionalisation make access to rights respecting services very difficult for excluded groups.

The attack on sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR), too – especially abortion – by fundamentalist religious groups both at the national level and exported through US government funding is compromising the ability of progressive donors such as the Swedish and the Dutch to ensure that SRHR is scaled up and included in health systems. The articles in this issue by Linda Weisert and Suzanne Petroni and Steven Allen provide clear guidance on where philanthropic investments in SRHR and mental health, respectively, can put communities first in defining the kinds of health services they need and advocating for government to provide them.

Don’t go it alone

The examples throughout this issue of Alliance strongly suggest that we cannot play our proper role in helping to end health disparities without addressing economic inequality and racism. It follows that we cannot fund health organisations alone, nor can we fund people to work on health in isolation from its underlying social determinants. We need to address the issues that affect the health and education sectors together during the Covid crisis. It is the same populations’ people of colour, with disabilities, with lack of economic resources, who can’t access a Covid test and don’t have a tablet to access their remote schools.

The opportunities for reimagining philanthropic investments in global health which we have put forward are driven by an analysis of the ills of the legacy of colonialism in the global health system and the ways in which this legacy is playing out through privatisation, health systems fragmentation and undemocratic and non-transparent health governance. It is our hope that this edition of Alliance will spark the conversations that we believe need to happen if philanthropy is to play a meaningful role in changing global health for the better.

Julia Greenberg is director, Governance and Financing, Public Health Program, Open Society Foundations, and guest editor of the December 2020 issue of Alliance magazine

Email: Julia.Greenberg@opensocietyfoundations.org

Twitter @jgreenb709

Aggrey Aluso is manager of Health and Rights Program, Open Society Initiative for Eastern Africa, and guest editor of the December 2020 issue of Alliance magazine

Email: aaluso@osiea.org

Twitter @aggrealuso

Footnotes

- ^ tinyurl.com/pandemic-profit

- ^ Other independent studies of maternal child health voucher programmes in East Africa show mixed results (gh.bmj.com/content/3/2/e000726) and similarly poor results for poor women (tinyurl.com/ESJ-voucher-programme)

Comments (1)

Quiet incisive n informative,I like the presentation n depth of research.