Community philanthropy organizations (CPOs) collect data for the purpose of donor compliance – numbers of grants awarded, people served, training sessions held, etc. What they don’t tend to collect are data on the other form of compliance: the extent to which they are actually doing what they promise – using community dynamics, leadership, knowledge, priorities and favoured ways of working to serve and strengthen communities. Collecting data is a necessary next step toward fulfilling that promise but research suggests that data on its own will not be enough to change behaviour.

The 2005 report, On the Brink of New Promise: the future of US community foundations argues that more often than not, foundations focus on their institutional sustainability rather than their core function of community strengthening, and calls for CPOs to remedy this.

There is a tension between the requirements of funders and the needs of communities. Institutional survival and growth depends, in a competitive funding environment, on meeting funders’ requirements. On the other hand, CPOs must secure a licence to operate by being responsive to community needs. These upward and downward pulls contribute to misalignment and present an operational and strategic challenge. So how can we assess the horizontal or vertical direction of CPO behaviour?

The question is, where will the impetus come from to put the community dynamic at the centre of community philanthropy? Should it be network and membership bodies committed to growing the field?

Horizontal or vertical?

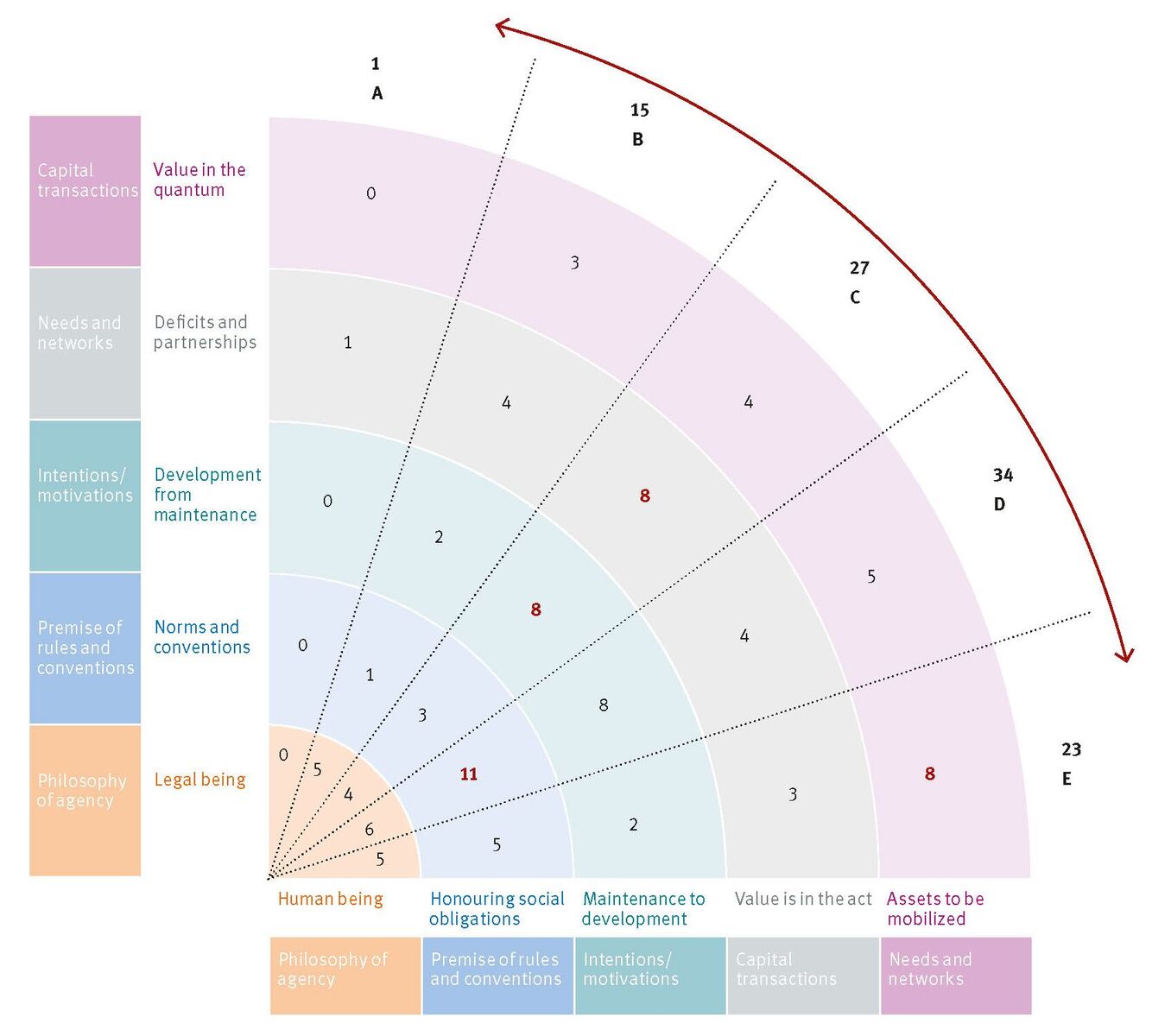

My research in South Africa in 2015 compared the typical characteristics of the aid industry with the community system of self-help. It produced five arcs or spectrums on which a range of behaviours could be located and from which a ‘horizontality gauge’ can be produced, to assess the extent to which an organization’s behaviour is closer to the vertical or the horizontal.

The vertical aid system: (i) sees gaps or needs that external resources can fill; (ii) is concerned with the quantum of giving (how much, how many), favours financial resources and is concerned with the efficiency of resource use; (iii) strives to help people escape poverty; (iv) is based on written agreements; and (v) recognizes people as legal entities – citizens with rights and obligations.

The organic helping system, deeply rooted in socio-cultural norms and feelings of belonging, by contrast (i) sees resources within a community that can be deployed to address that community’s needs; (ii) focuses on the social transaction of helping, ‘no matter how little’, with whatever is available – money, labour, support and skills; (iii) seeks to increase resilience to cope with, or escape from, current conditions such as poverty; (iv) operates according to unwritten yet widely established conventions, values and sanctions; and (v) recognizes people as human beings with an identity and dignity that need to be preserved.

Applying the template: three critical insights

Using this gauge, responses to a 2014 survey of executive directors, grant officers and administrators, head of programmes, field workers, board members, volunteers and interns from five community grantmakers in the Western Cape were plotted on an arc structured around a vertical and horizontal philanthropy axis.

Three critical insights into CPO behaviour emerged. First, behaviour is all over the map. Two CPOs favoured the mid-point, three leaned toward the horizontal and none favoured the vertical. Individualistic rather than formulaic behaviour suggests that compromises are often made according to circumstances and the ‘best possible’ approach to a situation is often adopted, rather than following an ideal.

Aligning CPOs’ work with their fundamental purpose is about promoting values and mission-based behaviour, engagement and accountability mechanisms, as well as adopting a systems perspective – an appreciation that CPO behaviour is not ‘whim’ but a response to forces.

Next, CPO behaviour combines the vertical and horizontal philanthropy conventions, reinforcing the idea that there is a behaviour zone where the two approaches blend. Two organizations had ‘aha’ moments: behaviour is not accidental, but a direct response to a donor requirement or community need. The gauge revealed what up to this point was a tacit or unspoken strategy for the management of vertical and horizontal pulls, suggesting that adherence to community philanthropy’s promise could require finding optimal ways to combine the vertical and horizontal.

Finally, while organizations came up with 13 uses for the horizontality gauge, they were all related to reporting, peer sharing and evaluation. None mentioned organizational development and self-correction. The implication is that CPOs as well as donors put the emphasis on upward accountability. The question is, where will the impetus come from to put the community dynamic at the centre of community philanthropy? Should it be network and membership bodies committed to growing the field?

Changing behaviour: all stakeholders need to be involved

So we have a way of measuring compliance to the community philanthropy promise, but can this measurement be used to produce learning and improvements in organizational behaviour?

Data is a starting point but it is not enough. It cannot change behaviour. Stakeholder intent, purpose and engagement with the data and the underlying problem of competing demands is required. Aligning CPOs’ work with their fundamental purpose is about promoting values and mission-based behaviour, engagement and accountability mechanisms, as well as adopting a systems perspective – an appreciation that CPO behaviour is not ‘whim’ but a response to forces. This suggests that the field needs a process whereby communities and donors are included in the conversation and the work needed to bring about and track behaviour change. This could include:

- A process for supporting CPO collection of compliance data.

- Examination of the value of a 360-degree assessment tool allowing communities to make their own assessment of CPOs’ organizational behaviour.

- Creation of network or coordinating body platforms where stakeholders can grapple with vertical and horizontal pulls and management strategies for a frank discussion about power dynamics, optimal accountability processes and practical action.

Ultimately, if measurement data is not to be limited to CPO self-reflection and rationalization, a process of engagement with donors and community leadership is crucial. If we engage as donors we know that our own requirements can work against the values and principles of the model and that we must find ways to relinquish power for greater flexibility. If we engage as CPOs, we know we can be more conscious of vertical and horizontal pulls and their implications for our own practice, and we can get better at putting effective strategies in place to manage these tensions. If we are engaging as communities, we know that our job is to promote our own leadership and centrality within the community philanthropy model and to work with CPOs in putting our resources front and centre and to best use.

Susan Wilkinson Maposa is co-author of The Poor Philanthropist: New approaches to sustainable development and a freelance adviser based in Cape Town, South Africa. Email swilkinsonmaposa@gmail.com

Comments (1)

Excellent article. Also just downloaded the "Poor Philanthropist". Excellent piece of research. Thank you so much for the article and study. Great work.