Philanthropy has a crucial role to play in supporting human rights groups to focus on people’s economic and social rights as well as promoting their civil and political freedoms

Human rights philanthropy is not a straightforward business. Supporting people to claim their rights involves funding advocacy efforts which may not be successful, court cases which may go on for years, and campaigns which may struggle to achieve concrete results.

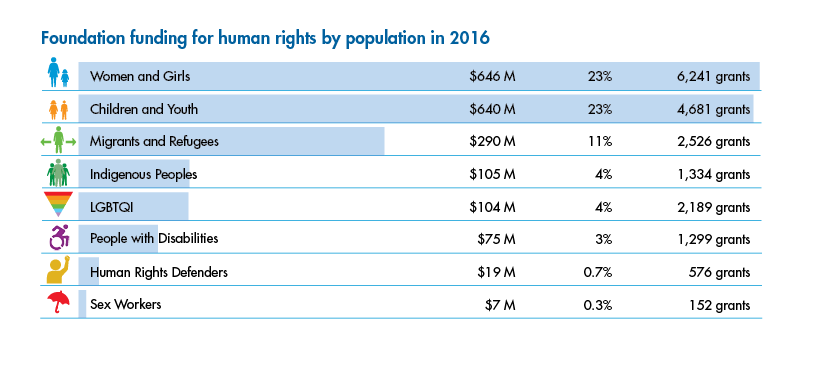

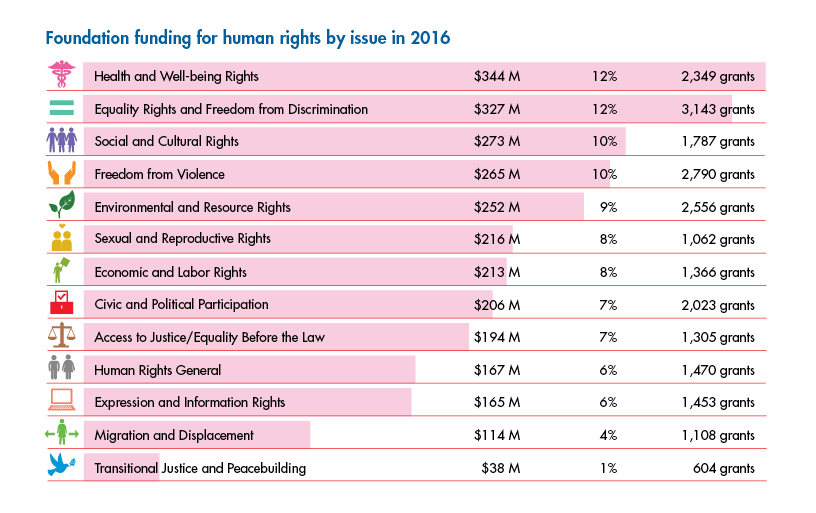

Yet support for human rights causes represents 5 per cent of all philanthropy, amounting to $2.8 billion in 2016, according to the latest figures collected by the Human Rights Funders Network and Candid.

Some of the states that initially signed up to the human rights treaties they oversee are now declaring that they will not be bound and constrained by their own commitments.

So what drives philanthropists and foundations to devote their resources to human rights? For some it’s personal – having experienced discrimination or abuse oneself or seeing it happen to friends or loved ones. Others come to human rights through concern for the most vulnerable in society and a desire to change the structures which create and sustain such vulnerability.

Today, the gap between rich and poor is widening, including in the most developed countries. Inequality is helping to drive social and political unrest, as many who fear they are losing out gravitate towards populist leaders and parties. The far right has gained traction by exploiting fears that others, particularly minorities and migrants, are taking resources away from the majority. Hence we are seeing a rise in xenophobia and ethnic and religious intolerance across many parts of the world.

We are also beginning to see the impacts of climate change, which is widely anticipated to have devastating effects for those already living in poverty. The World Bank predicts that by 2050 climate change could displace 140 million people from across the Global South. All of these factors mean that vulnerable populations are growing while those already at risk are becoming more so.

In the face of so many challenges, significant victories can be few and far between, but simply keeping the pressure on governments to respect human rights is important.

In this context, the principles of equality and non-discrimination enshrined in international human rights law are critical to thinking about how we resolve the problems facing us as a global society. Human rights give us a framework for addressing the abuse of power by states and corporations, and for lifting up the voice of those who do not have power.

Advances being increasingly challenged

Since the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights came into force in 1976, the human rights community has made many advances in protecting the rights of women, LGBTI people, ethnic and religious minorities, and people living with disabilities. Human rights protections have helped constrain states and made it more difficult for them to act with impunity.

But today these advances are under threat.

Many of the human rights mechanisms set up by the United Nations, Council of Europe, Organisation of American States, African Union and other regional bodies are being challenged. Some of the states that initially signed up to the human rights treaties they oversee are now declaring that they will not be bound and constrained by their own commitments.

Similarly, human rights organisations are under pressure in many parts of the world. They face difficulties registering and carrying out their activities, and accessing funding, particularly when it comes from international organisations or foreign states. Human rights defenders and other activists face both physical and digital threats to their safety and security. Such activism has always carried risks, but those risks appear to be on the rise.

What is the role of philanthropy for human rights then?

One role is simply to help keep the human rights movement alive. In the face of so many challenges, significant victories can be few and far between, but simply keeping the pressure on governments to respect human rights is important. Social change is a long-term endeavour. As the Oak Foundation’s Adrian Arena notes in this issue, sustained work can bring achievements in the long run even if the gains are slow and incremental.

Philanthropy should support local human rights groups doing pioneering work to promote civil and political freedoms alongside increasing the economic wellbeing and livelihoods of people and their communities.

Philanthropy can also help human rights organisations build greater support among the public. They can speak out in solidarity with the field, support communication efforts, and fund work that brings out the connections between challenges people face in their everyday lives and the tools the human rights framework provides.

Tables courtesy of Advancing Human Rights, a research initiative led by Candid and the Human Rights Funders Network.

Integrating ESC rights is key

Here, economic, social and cultural rights (ESC rights) – the rights concerning the basic social and economic conditions to live a life of dignity and freedom – are critical.

Too often, ESC rights have been viewed by governments, funders and even some in the human rights movement as aspirational – a body of ‘nice to have’ rights. This point of view has led to civil and political rights being prioritised over ESC rights. We fear this is a mistaken priority. Experience on the ground has shown that a neglect of ESC rights can alienate marginalised communities and risk painting human rights as elitist and disconnected from the basic needs of people.

Far right groups and populist politicians have been quick to exploit this gap by providing direct services and winning the support of large swathes of disaffected populations suffering from poverty, inequality and deprivation. However, as documented in this issue, grassroots social justice groups are fighting back and organising locally to reclaim ESC rights, holding authorities accountable and charting alternatives to the prevailing economic model.

Philanthropy has a crucial role to play in supporting these efforts but, to do so, it must build stronger connections between civil and political rights and ESC rights. That’s because human rights abuses are underpinned by deep social and economic inequalities which deprive people of their dignity and basic livelihoods.

Human rights do not only mean freedom from police harassment and arbitrary arrests, but a society in which everyone can access work, housing and education without discrimination and fear.

Philanthropy should support local human rights groups doing pioneering work to promote civil and political freedoms alongside increasing the economic wellbeing and livelihoods of people and their communities.

One example in this issue is the work of Space for Change in Nigeria. In the absence of legal representation for the poor, it works with rural and slum communities to reclaim ESC rights and push for state accountability through strategic litigation and advocacy.

Drawing on experience in Nigeria, its founder, Victoria Ibezim-Ohaeri makes a forceful case for the indivisibility of human rights and calls on the international human rights system and national constitutions to respect ESC rights and push for courts to offer a broader interpretation of rights. After all, she notes, ‘Does the right to free speech mean much to somebody that is too hungry, and too weak to speak?’

A renewed commitment to ESC rights will require more imagination from funders. The work takes time and resources and does not fit into quick timelines and an appetite for easy fixes and ‘results’.

While a growing number of funders are supporting work at the intersection of ESC rights and civil and political rights, more needs to be done to address the ongoing disconnect. Donors too often follow the traditional dichotomy with programmes addressing social deprivation framed in the language of ‘compassion’, ‘development’ and ‘service delivery’ rather than human rights.

Foundations also need to be more flexible in responding to the needs of grantees and local communities. Less rigidity can help them respond more effectively to requests from local groups. The Initiative for Equal Rights in Nigeria is a case in point. It realised early on that its work to protect LGBTI persons from violence had to go hand in hand with efforts to promote access to employment, housing and education. Human rights do not only mean freedom from police harassment and arbitrary arrests, but a society in which everyone can access work, housing and education without discrimination and fear.

Women’s rights groups in the Global South have long established a link between the low-income and education status of women and the likelihood of sexual and gender-based violence.

But for too many foundations, supporting ESC rights work still seems like a controversial undertaking because it seeks to challenge powerful economic and political actors and upend the entrenched economic and political systems that keep people poor and marginalised.

A human rights-based approach is ultimately a way of thinking and acting which goes far beyond funding specific standalone human rights projects or programmes.

A renewed commitment to ESC rights will require more imagination from funders. The work takes time and resources and does not fit into quick timelines and an appetite for easy fixes and ‘results’. While it can be intensive and long term, it is crucial if we are to meet the needs of communities and, in the process, rebuild and maintain trust and support for the broader message of human rights.

What are our long-term aims?

This brings us back to a key question and fundamental concern of each philanthropist, funder, and social investor: why do we do what we do?

Do we aim to maintain the status quo, simply alleviating some suffering or restoring some beauty? Or do we want to be a driving force for social change, contributing to shift power, participation and agency closer to people and local communities? As Ise Bosch asks in her recent book (Transformative Philanthropy: Giving with trust), do we want philanthropy to be transactional or transformative?

In these changing and challenging times, these questions are relevant for each and all of us, not only for those of us who define ourselves as ‘human rights funders’.

A human rights-based approach is ultimately a way of thinking and acting which goes far beyond funding specific standalone human rights projects or programmes. As a matter of fact, any area – climate, health, disability, education to name a few – can be funded differently using a human rights-based approach. It can be systematically integrated into every action, to expand the capabilities of people and communities to exercise their own fundamental freedoms, to make ‘duty-bearers’ accountable, and to empower people at local, national and international level, as Ndana Bofu-Tawamba points out in her article.

Philanthropy is well suited to supporting human rights work. It can take risks, be nimble, act flexibly, and stay for the long haul.

It should also lead us to re-consider our modalities of funding and be attuned to how deeply these modalities impact on the capacities, power and agency of our partners in the field – so-called grantees, recipients and beneficiaries. We need to overturn the donor-beneficiary power dynamics which repeat oppressive patterns and prevent our grantees from acting as owners of their rights. Current modalities of funding too often keep them as objects for protection and, in the worst case, in a situation of dependence.

Civil society organisations and movements need core support that is robust, predictable and sustainable, giving them confidence to seize new opportunities and create greater impact. And it almost goes without saying that funding for civil society organisations should be long-term, flexible and not necessarily project-based grants.

A human rights-based approach to funding should tap other forms of capital such as relationships, expertise and different types of support such as use of physical spaces, loans and guarantees – whatever is needed and can be legally provided.

Philanthropy is well suited to supporting human rights work. It can take risks, be nimble, act flexibly, and stay for the long haul.

The human rights movement is entering a state of transition. As contributors to this special feature show, there are significant opportunities and responsibilities for philanthropy to help it chart a new course towards a better, more equal global society.

Julie Broome is director of Ariadne.

Email: julie.broome@ariadne-network.eu

Twitter: @AriadneNetwork

Carola Carazzone is secretary general of Assifero.

Email: c.carazzone@assifero.org

Twitter: @CarolaCarazzone

John Kabia is fund programme officer for thematic initiatives at the Fund for Global Human Rights.

Email: jkabia@globalhumanrights.org

Twitter: @jmkabia

Comments (2)

As a Latinx Human Rights centered HIV racial justice, and immigration advocate, this article gives me hope and gives me strength to keep my fight for the dignity of my people. Thanks for sharing and elevating humanity.

Very useful article still learning alot in this field. Keep sharing . God bless Undule