‘It is when we all play safe that we create a world of utmost insecurity.’

Dag Hammarskjöld

2011 marked a watershed moment for democracy and development around the world. There were radical challenges to sclerotic power dynamics on every continent. Citizens and civil society groups seized a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to come together to challenge the entrenched paradigms of neoliberal economics and the gross inequity, planetary plunder and plutocratic alliances that underpin them.

Now, however, the optimism and rebirth of political engagement engendered by those developments is threatening to turn into scepticism, apathy and resignation to a return to business-as-usual. The reasons for this are many. As far as private donors are concerned, two things stand out: the lack of support for strengthening connections across borders and issues, and funders’ aversion to high-risk, high-gain investments in transformational change.

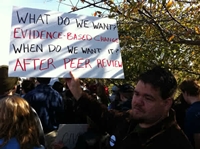

From the moment Wall Street imploded in 2008 to the point in late 2011 when citizen movements achieved global reach, traditional NGOs and the groups they depend on for their funding have, in the main, remained frozen in pre-crisis postures summed up by a placard at a demonstration in Washington DC in October 2010. It read: ‘What do we want? Evidence-based change. When do we want it? After peer review.’

From the moment Wall Street imploded in 2008 to the point in late 2011 when citizen movements achieved global reach, traditional NGOs and the groups they depend on for their funding have, in the main, remained frozen in pre-crisis postures summed up by a placard at a demonstration in Washington DC in October 2010. It read: ‘What do we want? Evidence-based change. When do we want it? After peer review.’

The need to join the dots …

At CIVICUS, where I worked at the time, it was patently clear that the need of the hour was a joining of the dots – convenings that bring together those with the deep, analytical understanding of the technical aspects of financial sector regulation, new economic models, climate science and global governance, with the grassroots movements that represent the millions who live or die by these policies. There is an urgent need to aggregate the learning and experience of hundreds of grassroots innovations and to amplify that synthesis to policymakers at a time when all the pieces are in play and there is everything to play for. We need forums for new thinking at a time when economics, pandemics, terrorism, climate change and communications technologies are global but the institutions to counter, develop or govern them are often not.

… and the attitudes that frustrate it

Every attempt to convene such gatherings have run into obstacles: silo thinking; bureaucratic and unwieldy decision-making structures at foundations and bilateral and multilateral funding agencies alike; short-term attitudes focused on protecting financial assets dented by stock market dips; technocratic mindsets that favour immediate, tangible, easily measurable activities over anything with a remotely ‘political’ agenda; and the dismissal of all forms of convening as mere ‘talk-shops’. As one civil society colleague expressed it: ‘Everything funders do seems to work as if to discourage different ways of imagining the road to social change.’

All about governance

As the crises have snowballed, and Wikileaks and others have revealed the width and depth of collusion between elected governments, tyrants and military, business and religious elites, it should be evident that any significant redress requires root-and-branch reform of international institutions and national systems of electoral democracy. In a world where these systems are still largely the prerogative of nation states, it could not be clearer that alternative civil society perspectives and voices – local, national, regional and global – are critical. It really is all about governance.

More than ever, two priorities remain vital. The need to protect and expand the spaces and freedoms that allow governance mechanisms that are fast losing their legitimacy to be challenged; and the need to build alliances between the groups that engage with the power structures and those with the political clout to influence attitudes within those structures. Instead, what we have seen at every international meeting, from the ICCC COPs to the G-20 summits, is the narrowing of avenues for civil society engagement and participation. Even states like Denmark and Canada that claim progressive leanings have responded with disproportionate force to any attempt to bring citizen voices within earshot of political leaders. Unsurprisingly, each global conference is deadlocked before it gets under way.

Domestically, too, non-violent dissent has been subjected to censorship, kettling, eviction and worse. At sanitized national and international gatherings and policy consultations civil society is increasingly ‘represented’ by elites from international NGOs, vertical funds (funds established to support focused thematic objectives), social enterprises, the private sector and foundations. Civil society groups dependent on state support find themselves as muzzled and constrained by their funders as politicians are by those they depend on to get elected.

Private donors unwilling to shoulder the burden

The response of many western governments to gargantuan fiscal deficits has been to cut public services domestically, at the same time as support to vital civil society infrastructure and to overseas assistance is either falling precipitously or at grave risk. Few philanthropic funders have been willing to help make good this shortfall. As a consequence, NGOs in the developed world face growing demand for their services from among homeless, unemployed and marginalized groups, on the one hand, and funding cutbacks and threats to their very existence for any criticism of these policies on the other. A significant number have chosen to restrict their activities to short-term, domestic concerns at the expense of longer-term, international programmes. The dearth of support from most philanthropists to fill these gaps exacerbates the chilling effect on advocacy aimed at resisting these threats or seeking systemic change. Groups that seek to defend privilege, in stark contrast, are awash in money.

In the global South, civil society groups that depend on northern support, especially those espousing domestically unpopular causes, pursuing long-term systemic and structural change, or challenging illegitimate, unaccountable governments, find themselves not only starved of resources but also bereft of diplomatic and moral support as developed country governments and philanthropists alike jockey for influence with emerging powers. In Central, South and South-East Asia, Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa, civil society groups fighting displacement of indigenous communities, corruption and anti-LGBT policies find themselves trapped between local mafias, private militias and state-sponsored terrorism, on the one hand, and donors and media mainly focused on the telegenic, advertiser-friendly story-du-jour on the other. Those in countries whose geopolitical significance has been greatly enhanced by the crises and those in countries far removed from the global spotlight have been hit particularly hard.

Private support for civil society groups, North and South, challenging or seeking to redefine the social contract is few and far between. Where available, it is vulnerable to the whims of individual philanthropists operating opaquely and accountable to none but their hand-picked boards.

CIVICUS’s 2011 report entitled Bridging the Gaps[1] clearly identified the challenges and opportunities. This year’s inaugural State of Civil Society report[2] further elaborates these themes. In brief, the need to build greater cohesion and solidarity among diverse civil society formations; to counter the rapidly growing threats to civil society freedoms; to facilitate collaborative visioning of new paradigms of sustainable, equitable development; and to radically reform institutions of global decision-making and governance.

More courage and humility needed

None of these things are susceptible to quick, simple solutions. None are easy to quantify, measure or report. Most are not amenable to tear-jerking viral videos or picturesque website images. They require a combination of dogged persistence and rapid response in place of the daunting bureaucratic, checklist-based assessments of proposals current among funders. Like the long struggles against slavery, colonialism, totalitarianism, apartheid and gender discrimination, they call for visionary, long-term funding support that eschews the technocratic bill of goods calling itself venture philanthropy or philanthrocapitalism.

This demands a minuscule fraction of the courage and resilience being demonstrated daily by activists around the world. It requires a willingness to sacrifice control and credit that very few donors currently display. At stake are the biggest potential gains for equity, sustainability and democracy in our time. No less at stake are the relevance, legitimacy and credibility of philanthropy itself.

1 Bridging the Gaps – Citizens organisations and dissociation: http://www.civicus.org/en/news-and-resources/reports-and-publications/588-bridging-the-gaps-citizens-organisations-and-dissociation

2 CIVICUS 2011 State of Civil Society report: http://socs.civicus.org

Ingrid Srinath was Secretary General of CIVICUS from 2008 to 2012. Email ingrid.srinath@gmail.com

Comments (0)