Currently only 2 per cent of philanthropic giving goes towards addressing climate change, however it’s clear that more is urgently needed. To mark the publication of our June issue, this webinar brought together a panel of experts to explore the critical role philanthropy has to play in funding climate solutions and technologies. This webinar was kindly supported by Fondation de France and produced in partnership with the British Foreign and Commonwealth Office and the British Consulate General New York.

Moderated by Charles Keidan, executive editor for Alliance magazine, the speakers were: Jennifer Kitt, Founding President of the Climate Leadership Initiative; Nigel Topping, High Level Climate Action Champion for COP26; Winnie Asiti, Member of Next Generation Climate Board of the Global Greengrants Fund, Kenya. Hannah Young, Deputy Consul General for the British Consulate General New York, gave opening and closing remarks.

Hannah Young

Hannah Young

Following Charles’ introduction to the webinar, Hannah Young gave opening remarks and spoke briefly about the COP26 summit in November, which is being hosted by the UK in conjunction with Italy. COP26 is an inclusive summit encouraging countries, states, businesses, and civil society to come forward with ‘enhanced climate commitments.’ Young also spoke about the work the British Consulate General New York has been doing to connect UK and US experts to ‘share best practice and raise ambition’ on many topics including ‘private finance, offshore wind and electric vehicles.’

Philanthropists can play four roles in tackling climate change: shaping the climate debate, building networks, investing for climate, and funding climate initiatives. Young stated that the ‘scale and pace of the transition is huge’ and therefore requires ‘all forms of finance to drive that change.’ Philanthropists must use their ‘powerful voices to direct the funds and activities of larger investors and corporations towards a net zero resilient future.’

Nigel Topping

Nigel Topping

Nigel Topping started by saying that ahead of the COP26 Summit, ‘we are a long way from being on track’. The ‘likelihood of breaching 1.5-2 degrees has gone up’ and ‘the risk associated with those temperature increases is high.’ However, we are making huge progress; the G7 have ‘committed to net-zero…increasingly focusing on the need to halve emissions by 2030’. There are also commitments from businesses and investors.

However, Nigel noted that even if ‘you add up all of the improving country plans you still get way beyond 2 degrees’ and emphasized the amount of work that needs to be done to keep global warming under 1.5 degrees. He brought up the huge gap between ‘ambition and policies and actions’ and the need to ‘focus on what people are actually doing in the next 5, 10 years.’

Nigel addressed the climate finance gap and the obsession with the ‘100 billion totemic figure [that] the global north committed to the global south in terms of climate finance.’ However, the ‘world needs to deploy 4 trillion dollars’ worth of capital every year to make the investments needed to get to a zero carbon resilient economy in the global south.’ While G7 have strongly confirmed their commitment to delivering the 100 billion, there is still an execution gap and it hasn’t been delivered yet.

Nigel then highlighted a few key roles that philanthropy can play in tackling climate change:

- Driving collaborations. Nigel referenced the We Mean Business Coalition as a ‘visionary piece of philanthropy’ from the Ikea Foundation.

- Being able to quickly deploy key staff to bridge gaps

- Innovating in the gap between what markets will do and what policy makers are ready to do. Nigel mentioned the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) as an example of a project that was initially philanthropically funded.

He also discussed the role of philanthropy in relation to the private sector, saying that there is a ‘tautology in philanthropic thinking that says “we’ll fund the policy change, but we won’t fund the private sector change.”’ He gave several examples of philanthropically funded climate projects that use tools from the private sector to change the behaviour of the private sector.

He called for more ‘courageous philanthropy’ that is willing to innovate to change the way markets work. He stated that ‘being allergic to intervening in the private sector because the private sector should sort itself out is inconsistent.’

Poll

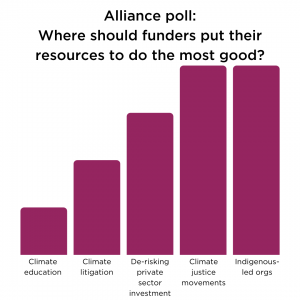

The audience was asked to partake in a live poll answering the question: where should funders put their resources to do the most good?

The audience was asked to partake in a live poll answering the question: where should funders put their resources to do the most good?

Initial live responses were: 20 per cent directly to indigenous led organisations, 20 per cent climate justice movements, 15 per cent de-risking private sector investment, 10 per cent climate litigation, 5 per cent climate education.

Charles briefly referenced the Climateworks data that states ‘only 60 million dollars goes [to climate justice movements] out of the 1.6 billion dollars a year of climate funding.’

Jennifer Kitt

Jennifer Kitt

As part of Alliance‘s year long 25th anniversary celebrations, Jennifer was asked to reflect on the role of philanthropy in the past 25 years regarding climate action; Jennefir argued ‘philanthropy has helped push global governments and businesses in all kinds of ways, so that we’re no longer on track to an overheating planet of 4-6 degrees, which is what it was 25 years ago. The bad news is that we’re still close to 3 degrees overheating, even if the Paris climate agreement commitments are implemented.’

Jennifer spoke of the urgent need to implement change to tackle the climate crisis, and how philanthropy can help speed along the process. She gave some examples, including the Beyond Coal campaign in the US, which she called ‘one of the most successful things philanthropy has ever done in the climate area.’

About $250 million of philanthropy went to this project, which funded bootcamps that taught lawyers how to block polluting coal permits, training for community members, workshops and strategic communication. The project succeeded in shutting down the very worst polluting coal plants in the US. The project has now spread across the world to fund clean energy solutions with geographically appropriate strategies.

Jennifer was keen to stress the importance of collaboration to scale climate solutions faster, and discussed how protecting nature is ‘one of the most powerful solutions for an overheating planet.’ Indigenous people steward their lands in a way that helps protect their ecosystems, therefore ‘investing in indigenous people’s land rights, and protecting and formally documenting them, has a very high return on investment for protecting the ecosystems that in turn protect us.’

Being allergic to intervening in the private sector because the private sector should sort itself out is inconsistent.

Though there are already groups working towards this, Jennifer noted that it was one example of a collaborative giving project that could be scaled with more investment, noting that currently ‘less than 2 per cent of global philanthropy is going to solving the climate crisis.’

Jennifer echoed Nigel’s sentiments on the urgency of the crisis: ‘In the next nine years scientists have made it clear that we have to cut emissions in half, and then continue to do that every decade until we get to… net-zero or almost no emissions at all from fossil fuels by the middle of the century, 2050. That is actually a level of change that we have never done as a community.’

Jennifer briefly spoke about the intersection between climate funders and funders in other areas, making it clear that climate funding is in everyone’s best interests. ‘Climate solutions are making life better for people, you can intersect your interests and have very powerful solutions that help us solve the problem at the same time as helping us make a better world.’

Winnie Asiti

Winnie Asiti

Winnie Asiti was the guest editor of Alliance’s June issue on climate philanthropy. She began by speaking about the urgent need to increase funding for climate action, particularly in the global south. She called on funders to ‘consider funding climate action as part of their other funding, even if they’re not specifically climate funders.’ She also stressed the importance of integrating ‘climate as part of their own organisational workings by ensuring that they are divesting from fossil fuels.’

Winnie stated that funding should be invested in grassroots organisations, to help the young people, women and indigenous communities at the frontline of climate change. She spoke of some of the impacts climate change has had on these communities, from people living in the Amazon who are grappling with the impacts of climate change to pastoral communities that are no longer able to continue keeping their livestock because the changing climate is making it more unsustainable.

She also spoke about her work as part of the Next Generation Climate Board, and the huge positive impact that has resulted from giving small grants of around $5,000 to youth organisations in the global south. She referenced the Arab Youth Climate Movement in Iraq who advocated for unleaded fuel in their country, and the 2020 Ghanaian winner of the Goldman Environmental Prize.

Winnie briefly discussed the importance of funding climate justice movements which can ‘mobilize awareness…to more forcefully advocate for change.’ She also cited a study that found for every ‘1 dollar invested in climate funds, the returns are up to $4.’ Therefore, investing in climate action is a smart, long-term investment with good returns.

Winnie was optimistic about trends in climate funding, as the number of climate funders is increasing. She laid out her hopes for achieving ‘transformative climate philanthropy’ in 2030 where funders are ‘funding meaningfully’ by ‘encouraging models of participatory grant-making where those that are receiving funds actually have a voice and a role to play in making decisions on what is important to them.’ She also hopes to see more young people and communities on the frontline of decision making, ‘not just in philanthropy, but in very critical processes like the upcoming COP26.’

Tracking climate funding

Charles questioned whether there was a need for a system or platform to hold climate funders to account, similar to how the climate action tracker holds governments to account. Nigel explained that the tracker is a collaboration between several ‘expert NGOs and academics’ that had been ‘very effective.’ He praised transparency in the industry, though questioned who philanthropy should be held accountable to.

Jennifer Kitt also weighed in by pointing out that there are already many existing collaborative platforms and organisations tracking where climate funding is going, and that money should be flowing towards solutions and new collaborations.

Q&A

Charles then opened the floor to questions from the audience. The first was from Mark S. McCaffrey, from the UN Climate Change community for education, communication, and outreach stakeholders. He asked what it would take for climate funders to recognize the importance of youth and community engagement around climate, and what more could be done there.

Jennifer stated that she’d already seen a fair amount of community engagement, though more is needed as ‘it is people that have to demand things of their governments, of their companies and of their systems’ for change to happen. She noted particularly strong engagement from youth, who understand the climate science as they were taught it in schools and stressed the importance of youth engagement in climate funding.

EFC’s environmental funding mapping report by Jon Cracknell

Jon Cracknell from the audience mentioned the need to challenge the political power of the fossil fuel industry and asked how this might be done. Nigel took this question, listing several ways such as funding research into the job creation potential of clean alternatives, tackling investor roots, lobbying, and changing company regulations. He stated that the only way to tackle this issue is to ‘dissect it down to a lever that you can actually apply pressure to, and that comes down to a legal instrument, data instrument, a policy instrument or an intellectual argument.’

Winnie followed up by saying ‘private sector players normally respond really well to regulations’ and that it can be difficult for them to be at the frontlines before the regulations have been put into place. Therefore, philanthropy could invest in the processes that support this.

She also commented on the climate education question by saying ‘communities that are…experiencing the impacts of climate change have a lot of knowledge and education to offer.’ She discussed how in these communities, knowledge about dealing with climate change is often passed down intergenerationally. She noted the value of this knowledge that comes from lived experience, of how ‘communities have survived these changes and how they continue to adapt to their circumstances.’

Charles then brought up Jeff Bezos’ Earth Fund, which has committed $10 billion to climate funding, and asked the panel for their thoughts on it. Jennifer praised the initiative and the Earth Fund’s leadership, saying she expected it to be a ‘model for others’ and that she hoped other philanthropists with large resources would also commit to the cause.

Nigel added that ‘funders need to go big, long-term and flexible’ to remove some of the payroll stress from talented leaders in NGOs so that they can get on with making a change. One of the things such commitments could do is ‘free up some of the human talent which is what drives all the change.’

Charles addressed inconsistency in the sector with his next question, asking: ‘are there concerns that some of the large climate funders, such as the Hewlett Foundation or the Wellcome Trust, are still investing in fossil fuels in order to maximise their returns?’

Communities that are experiencing the impacts of climate change have a lot of knowledge and education to offer.

Winnie answered by emphasizing the need for ‘a much more amplified call for funders to practice what they are trying to address. You can’t be talking about moving towards net-zero and so on but still continue to invest in fossil fuels.’ She brought up the court case against Shell, where they were legally obliged to set up climate commitments, and the need to invest in more litigation to get corporations to commit to climate targets. She added that this also applies to philanthropy, and that foundations need to ‘lead from the front.’

Nigel added, ‘if you’re philanthropically funding a societal change and you’re not grappling with that same environmental change on the endowment side, first of all you’re definitely being inconsistent, and second of all one of you is going to be wrong.’ He pointed out that endowments invested in fossil fuels have lost value, and that philanthropists ‘may have better insights into the way society is changing than the people on the investment side.’

He stated that there is ‘a moral argument and a financial argument’ and trying to ‘make the change through the investment chain might well lead to real insights in terms of what needs to be funded philanthropically.’ Nigel advocated for getting rid of the ‘artificial walls’ between the philanthropic and financial worlds, and for those on both sides to learn from each other.

Rajiv Khanna from the audience asked: ‘a lot of sustainable and effective climate solutions are coming directly from climate justice movements around the world that have been chronically underfunded. This is a “big bet” that has been grossly overlooked in climate philanthropy. Could this be an area that is poised for expansion?’

Winnie answered by saying there is an opportunity to upscale existing climate justice movements, especially as they are ‘vehicles through which we can achieve much more action and keep the momentum going.’ She cited the impact Extinction Rebellion has already had, saying that ‘increased and sustained funding to such movements’ will enable them to be ‘capable of holding governments, philanthropists, and all the players that are involved to account.’

Jennifer talked about the challenges of scaling philanthropy and the need for more multi-year funding for this to happen, especially for climate justice groups and grassroots groups. Nigel added that societal change is systemic and will take interventions from every part of the climate action ecosystem, with ‘all major levers being pulled at the same time.’

The webinar concluded with closing remarks from Hannah Young, who echoed the sentiments of the panel: ‘we must match the urgency of this moment and ask ourselves what more we can do.’

Annmarie McQueen is the Marketing, Advertising & Events Manager at Alliance

Watch a recording of the discussion below:

Comments (0)