For many working with philanthropy, there is always a twinge of discomfort.

Philanthropy itself arises out of an unequal system where a few individuals are able to accrue far more wealth than they actually need, and then, at the behest of their own whims and fancy, they decide who should get some of their ill-gotten spoils and how should they get it. It requires a bit of double-think in your work: you close your eyes to the origins of the funding and even the decision-making models and try to accept that the outcomes are more important than the means.

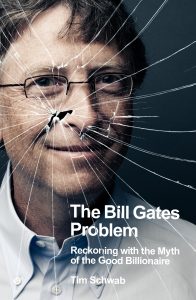

But even with the awareness of the compromises I accept in my work, reading Tim Schwab’s forensic expose, ‘The Bill Gates Problem, Reckoning with the Myth of the Good Billionaire’ made for some very uncomfortable (and gripping) reading.

But even with the awareness of the compromises I accept in my work, reading Tim Schwab’s forensic expose, ‘The Bill Gates Problem, Reckoning with the Myth of the Good Billionaire’ made for some very uncomfortable (and gripping) reading.

Schwab reveals Gates’ influence across public health, journalism, vaccinations, the pharmaceutical industry, agriculture and even women’s lives in global majority countries. All of these have one primary thing in common toward recreating these sectors in the same way he put his stamp on Microsoft: an ideological adherence to trickle-down economics, controlling markets in a monopolistic fashion and avoiding scrutiny.

For those that think, well, as long as they pay taxes, then that’s fair, this book will force you to think again. Schwab also reveals how Gates, and indeed other billionaire philanthropists, aren’t just avoiding tax, they’re actually being subsidised by the state for their philanthropy through tax breaks and complex organisational accounting practiced by the likes of the multi-national companies that they once presided over. They have effectively privatised public goods and shaped charity to fit with their own world view.

And that world view is one that is rooted in neo-colonialism. In several chapters, Schwab finds evidence that shows this bias towards western-led solutions, one that sees people of colour in need of ‘saving’, never able to solve their own problems. ‘We’ll see a foundation with a retrograde colonial gaze that leans hard on high-paid technocrats in Geneva and Washington DC, to solve the problems of poor people living in Kampala and Utter Pradesh.’ The foundation’s business model that prioritises funding – even for so-called African-led initiatives – to those who are US based only further serves to reinforce this view, or the billions going to McKinsey or other corporate consultancies.

‘Particularly worrying was the rapture that many in the media and government are prepared to pay at the throne of Gates, and how the Foundation has managed to ensure that all institutions are beholden to them as a result of their financial largesse’

In Chapter 13, Schwab provides the example of Gates’ ambition to introduce GMOs to Africa, and to industrialize farming using western-led technology. ‘The premise of the Gates Foundation’s work is that African nations don’t have the expertise or capacity or tools to manage their own food systems – that they need professionals and experts from the Global North to help them.’

And, argues Schwab, that effort has largely failed to deliver the promised new Green Revolution (known as AGRA), a view supported by a Scientific American article in 2022. ‘Since the onset of AGRA’s program in 2006, the number of undernourished people across these 13 countries [where AGRA works] has increased by 30 per cent,’ says a letter from African organisations asking Bill Gates to effectively stop helping.

Indeed, in my own work on the food system, some years ago, with Fairtrade producers in India, it was widely proven that farmers who prioritised organic, local seeds through mixed farming methods, alongside fair access to markets, were far more resilient and productive than those who had been offered GMO technology.

The ‘white gaze’, the author finds, is everywhere, presenting some compelling examples like the derogatory view expressed by Melinda Gates in 2022, of African or Indian women holding babies on their hips: ‘when you go in places in India, you know, you often see a mom with a baby strapped on her back, and maybe she’s cooking over a boiling pot of water because she’s selling what she’s cooking. That’s really unsafe for a baby; you get a lot of accidents.’

Or ‘you see a lot of adolescents, young adolescent girls with a baby on their hip during the day running around in unsafe places and traffic with the baby’s head kind of bobbling around. But think about what it means for the baby…..on the converse side, you get them in safe, affordable child care, that baby can thrive.’ This view, in particular, received significant backlash on social media, writes the author.

After reading this, it’s unsurprising to find that the Gates Foundation is not amongst the leading 15 philanthropic organisations who have joined a pledge on strengthening locally-led development, following USAID’s lead.

Particularly worrying was the rapture that many in the media and government are prepared to pay at the throne of Gates, and how the Foundation has managed to ensure that all institutions are beholden to them as a result of their financial largesse. The author recounts how funding to every institution from media to the World Health Organisation ends up dictating their priorities. He refers to the ‘weapon’s grade nuclear material it has in its arsenal to win influence’ through donations to newsrooms, international policy forums and lobbyists. One example given is the $12 bn to organisations around Washington DC, more than the amount spent in the whole of Africa.

Outcomes are always difficult to measure in philanthropy, but one thing that Gates has majored in is the impression that evidence matters. Widely wielded success statistics, like the millions of lives saved as a direct result of Gates’ work, are headlined in all of the materials from the foundation, and through the messages passed through the media. However, Schwab provides evidence from multiple expert sources that much of the acclaim in based on dubious claims about cause and effect.

The problem, says Schwab, is that none of these statistics are verifiable through independent sources because of the unaccountable nature of the organisation. The lack of scrutiny is ensured for anyone wanting to engage in Gates, as staff, affiliates, contractors and grantees all have to sign non-disclosure agreements that threaten anything they say externally, even long after they have left the organisation.

‘Schwab touches throughout on the unaccountable nature of philanthropy, noting that of 100,000 foundations in the US alone, only 200 per year are ever audited. And that the rules of the game haven’t changed since the 1960’s.’

What has eluded Gates is a day of reckoning. Unlike others who were exposed for their affiliation with Jeffrey Epstein, many who had to resign or apologise, Gates managed to shrug this off, in spite of maintaining a friendship after Epstein was convicted in 2008. Though Foundations like Ford and Rockefeller have apologised for questionable past funding, population control, these have entirely passed Gates by. He has successfully purchased, cultivated, and permanently secured the halo effect of the ‘good Billionaire’. So much so that his wealth has grown by at least a third since stepping down from Microsoft, as Schwab draws a blurring line between Gates’ ongoing corporate and philanthropic interests.

Schwab doesn’t like philanthropy, at least not billionaire-led philanthropy. The conclusion of the book is a damning indictment, not just of Bill Gates and his foundation, but of billionaire philanthropy as a whole. Schwab touches throughout on the unaccountable nature of philanthropy, noting that of 100,000 foundations in the US alone, only 200 per year are ever audited. And that the rules of the game haven’t changed since the 1960’s. He calls for a long-overdue change in how philanthropy is regulated, like a requirement to draw down on endowments faster, something that has started to gain some traction; a new era of transparency; as well as appointing boards who are independent of the founders, drawn from intended beneficiaries of the foundations.

And mostly, he calls for far higher taxes on the rich; why do we allow so much wealth to accrue into the hands of a few, he asks? He cites the example of Meta’s Mark Zuckerburg who isn’t using the tax breaks allowed for philanthropy, but has instead set up Limited Liability entities to give away his money, a method even more opaque than Gates. Regulating philanthropy, argues Schwab, isn’t enough. ‘As long as Bill Gates maintains his extreme wealth, he will remain a canker on democracy.’ ‘If not through his private foundation, then through other means.’

It’s a brave journalist who takes on the job of investigating the Gates Foundation, and Schwab’s book is a must-read for any of us who are working in this sector, anyone who regulates the sector and anyone who cares about equality. Even if we haven’t received Gates’ funding directly, we will have been influenced by their work through some means or other. The question isn’t how to direct Gates’ funding better, says Schwab, it’s to not allow him to have so much wealth and power in the first place. And we’re all complicit, to an extent, in enabling that.

Deborah Doane is Partner at Rights CoLab and Convenor at the RINGO Project.

Comments (0)