Experts John Kania and Cynthia Rayner lay out concrete ways that social investors can incorporate the principles of systems change into their day-to-day activities.

Jordan Kassalow had his first “lightbulb” moment at the age of 23. While volunteering on a medical mission in the Yucatán, he conceived of a social enterprise to distribute eyeglasses affordably while lifting up local economies in under-resourced countries. Since 2001, VisionSpring has distributed 8.7 million corrective eyeglasses in 53 countries worldwide, generating US $1.8 billion in economic impact.

But it was his second “aha!” moment that was the most ambitious. Kassalow recalls, “About eight years ago, it became eminently clear to me that we needed a different approach. My beard was getting a little gray, and I saw my time was running out. We reached many millions of people, but this was a problem affecting over a billion people.”

Kassalow had to admit that VisionSpring couldn’t solve the problem by itself. “It became pretty clear that there was no NGO that had scaled to billions of people. NGOs were good at coming up with innovative models and building things up to a degree. But they weren’t massive scalers. So we began to ask, who are the massive scalers? It basically came down to governments and the private sector.”

But the problem wasn’t just an issue of scale. While public procurement of eyeglasses is solvable, in many countries there are strong opinions about who should deliver eye care. There are also cultural taboos about wearing glasses. These deeper issues stem from power and control in the medical establishment, trust between nongovernmental organization partners and public health professionals, and persistent social norms.

Kassalow and Liz Smith, VisionSpring’s director of business development, began to look at the problem from a different perspective. What kind of support would a government need to provide eye care to everyone in a country who needed it? Which partners could provide this support and who would finance it? More fundamentally, was VisionSpring the right organization to deliver this support and financing, and if not, who would do it?

These questions didn’t have easy answers. To craft workable policies and challenge power dynamics, a new web of relationships needed to be built and nurtured. Kassalow and Smith realized this web would need to be orchestrated by a neutral player. In 2016, they incubated and launched a new multi-stakeholder initiative, the EYElliance, to bring together the necessary players to approach the complex issues they had identified.

Five years later, EYElliance has assembled 55 partners with ambitious 10-year targets they are on track to achieve, including eyeglasses for 350 million people in over 20 low-income countries. These targets are exponentially larger than what VisionSpring could achieve on its own, and they required a step in a different direction to gain sight of the larger vision system.

Most social and environmental problems require comprehensive changes in public and private systems, structures, policies, and social norms to make long term sustainable progress. This deeper, more holistic way of working has come to be known as systems change, an approach that can be defined as “shifting the conditions that hold a problem in place.”

Defining Systems Change

Kassalow’s experience with equitable access to eyeglasses demonstrates that outcomes and solutions that focus on the root causes of social problems cannot be achieved solely through addressing people’s direct needs. Most social and environmental problems require comprehensive changes in public and private systems, structures, policies, and social norms to make long-term sustainable progress. This deeper, more holistic way of working has come to be known as “systems change,” an approach that has been defined by Social Innovation Generation, a collaborative systems change partnership in Canada, as “shifting the conditions that hold a problem in place.”

While systems change is increasingly part of the dialogue in philanthropy, it remains little understood. Yet, systems change is a concept that is already embedded in philanthropic work for those seeking to focus on the root causes of problems. By adding deeper practices to the philanthropic toolbox, social investors can be better prepared to make real and lasting change in the short and long terms.

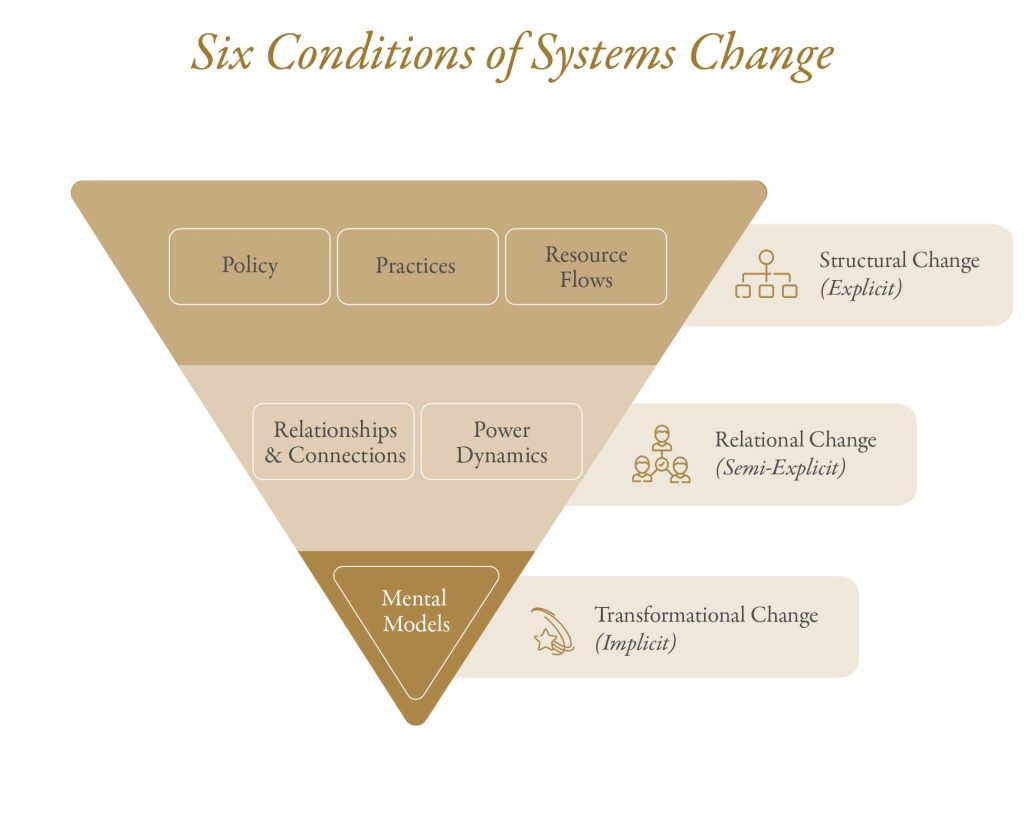

One framework that has proven useful to many is to consider system changes at three levels of explicitness (see diagram). First is the level of structural change: shifts in policies, practices, and resource flows. This level is explicit, in that people engaged in the system can readily identify these conditions. Second is the level of relational change — specifically, relationships and connections, and power dynamics among people or organizations. This level tends to be semi-explicit in that sometimes the changes happen out of sight of some players in the system. The third level of systems change is transformative change — the mental models, worldviews, and narratives underlying our understanding of social and environmental problems. Mental models are typically implicit but have the most power to guide individual and system behavior over the long term.

Many engaged in systems change work tend to overinvest time and resources in attempting to change conditions at the structural level. Such solutions are important. However, changing structure without shifting relationships, power dynamics, and mental models can lead to irrelevant, ineffective, unaccountable, and unsustainable solutions.

Though systems change has lately become a greater part of the philanthropic discourse, the approach is far from new. Throughout history and across the world, people have organized for social change at the systems level. In recent years, advocates of systems change have focused on the legacies of systems science and thinking, highlighting the contributions of scholars such as Jay Forrester and Donella Meadows. In addition, more relational, long-standing approaches to systems change have also been developed and practiced over the centuries by activists, community organizers, philosophers, and educationalists.

Shifting to systems approaches usually requires moving away from funding individual organizations in isolation and instead resourcing collective efforts that bring together many organizations of all types to work for change.

Seeing the System

While some organizations come to systems change through the experience of scaling a successful program, others have tackled issues systemically from the beginning. One such organization is Girls Not Brides: The Global Partnership to End Child Marriage, a diverse network of over 1,600 civil society organizations in more than 100 countries working to end child marriage around the world.

Girls Not Brides was founded in 2011 by Mabel van Oranje, who, at the time, was CEO of The Elders, an independent group of global leaders founded by Nelson Mandela. While researching issues of gender and, equity, van Oranje was shocked to learn that child, early, and forced marriage and unions affected 12 million girls worldwide annually. It seemed like a problem hidden in plain sight. As Faith Mwangi-Powell, CEO of Girls Not Brides, explains, “Issues of social and cultural norms are sometimes surrounded by a ‘conspiracy of silence’ because people are afraid to talk about them.”

Issues that derive from relationships, power dynamics, and social norms cannot be solved by single interventions. They require a complex set of changes that transform the way a majority of people think, believe, and act. Mwangi-Powell goes on to say, “Even if we have the law, even if we have the financing, even if we have all these great tools, if the communities are not acting to create an enabling environment in which girls can thrive, then the cycle is not complete.”

To address this complex issue, Girls Not Brides has created a multilayered movement. At the global level, the secretariat works to raise awareness and mobilize political and financial commitments, with recognition that child marriage is a challenge in all countries, not merely a niche issue affecting a small portion of the world. At the national level, network leaders build strong coalitions of stakeholders, assembling representatives from education, economic, and traditional sectors to implement and strengthen policies and laws that prevent child marriage. Finally, at the community level, civil society organizations work with families, faith leaders, and most importantly, girls themselves to shift perceptions of life opportunities and alternatives to early marriage. And all these actors come together under the Girls Not Brides umbrella to learn and advocate collectively for a world free from child marriage where girls and women enjoy equal status with boys and men.

There is no “magical mix,” van Oranje is quick to say, reminding us that each country and community has a specific set of circumstances that country and community-based partners are uniquely suited to address.

As the stories of EYElliance and Girls Not Brides illustrate, making the shift to systems change requires social investors to transform their own mental models about who, what, where, and how to fund:

Individual to collective. While individual organizations often alleviate the symptoms of social issues, it is rare for them to fundamentally change systems. There is a truism of systems change, namely “if you want to change the system, get the system in the room.” Shifting to systems approaches usually requires moving away from funding individual organizations in isolation and instead resourcing collective efforts that bring together many organizations of all types to work for change.

Programs to systems. Funders often seek out programs that offer discrete changes in response to simple problems. These are the things that can be easily measured: commodities, interventions, infrastructure, trainings. However, social issues are more often issues of complexity. Single solutions are rarely sufficient. Louis Boorstin, managing director of the Osprey Foundation, which funds organizations that strengthen local, regional, and national water and sanitation systems, understands this well, explaining “Many small funders will focus on getting people hardware or basic services. That’s OK, but what organizations that strengthen systems also need is flexible funding so that they can build local capacity, change mindsets, and try new approaches. At the end of the year, you won’t be able to say, ‘I paid for that tap or that latrine.’ But you’ll end up having a much more leveraged and sustained impact.”

Proficiency to proximity. Funders typically spend significant resources to analyze issues with great proficiency. Empirical knowledge and formal expertise are critical. But systems issues are deeply contextual and require being embedded in the community and lived experience to fully grasp. Systems change funders will often need to make the shift from funding top-down interventions to working closely with proximate leaders who have legitimacy and trust in communities. For example, Andy Bryant, executive director at the Segal Family Foundation, explained how their work in sub-Saharan Africa has been transformed by moving to 85% local partners in their grant portfolio. This move, coupled with local hiring and moving all funding decisions to their on-the-ground staff members, has made the foundation smarter, says Bryant. “We can see around corners, bringing a huge amount of localized knowledge and context to any decision.”

Technical work to relational work. Most fundamentally, systems change requires that funders move from approaches that optimize the elements of a system to approaches that alter the interconnections between those elements. This requires long-term vision and ongoing consideration about who is involved in the change effort, how they are relating to one another, and ways they can influence the system. Mwangi-Powell describes it as, “sitting in a circular place, and always moving the chairs back so that you’re creating more space for other people to join, thinking about: Who else needs to be here?”

The work of systems change, is about working in an iterative fashion. Do your homework well, but don’t wait until you have all the answers. Learn by doing. Mabel van Oranje

Investing in Systems Change

Investing in systems change requires engaging with the full complexity of social and environmental problems. Complex systems are made up of many variables interacting with each other, and we understand them intuitively because we live in a nested set of them: our bodies, our families, our communities, and the natural environment. We also understand — either implicitly or explicitly — the patterns, feedback, and cycles that complex systems exhibit. Each part of the system affects all the other parts, and the relationships between each connection point, or node, must be understood in order to make a material change to the whole system. A Band-Aid won’t work on a broken arm; you have to reset the bone and then make sure all the other parts of the arm contribute to the bone’s healing. Systems change investing is typically more nuanced than investing in programs. But it also holds exciting possibilities for donors wishing to affect social change at a deeper level.

Below we list several systems change opportunities available to social investors.

System catalyst or orchestrator. Because systems change work engages multiple organizations and constituents working collectively, there is often a need for an organization to play a role that is variously known as system catalyst, backbone, or orchestrator. EYElliance is playing this role in inclusive eye care. Girls Not Brides is playing this role in the movement to end child marriage. Organizations engaged in system orchestration work in highly relational ways to bring parties together, influence policy change, and galvanize efforts to gather and analyze data, engaging system players in collective seeing, learning, and doing. Boorstin from the Osprey Foundation describes this as a significant opportunity: “Funding [an orchestrator] is hard for many funders as you’re two levels away from service delivery. But the way Osprey looks at it, by funding a hub for systems change we’re influencing multiple organizations operating in dozens of countries to work more collaboratively and effectively. In turn, that impacts how households, communities, and governments choose to spend their money. That’s great leverage.”

Advocacy and activism for policy change. Many long-term philanthropists who begin by investing in programs find that eventually they are led to focusing on policy. “It becomes inevitable,” said one Silicon Valley philanthropist, “if you want to see real change happen.” Policy agendas exist today in many social change arenas. For example, for Girls Not Brides, a key part of the policy agenda is advancing adolescent girls’ rights and agency. Often, for specific issues, there is one or several organizations (in some cases, as mentioned previously, this is the system orchestrator) who focus on advocating with policymakers, thereby providing a targeted way for donors to invest in policy change.

Narrative change. All of us have mental frames that we carry in our heads as a product of our values, the culture we live in, our experiences, and our relationships. Narrative change is about shifting existing mental frames to new ones. It is arguably the most powerful lever in systems change, though not easy to do. For some donors, investing in the research behind or delivery of narrative change can be a compelling investment that helps make palpable the problem and the solution through the process of changing people’s hearts and minds.

Community mobilization. The Segal Family Foundation sees firsthand the power of community mobilization. Bryant offers, “A big area of investment for us is building community. It’s a very ground-up thing, creating close-knit relationships among our grantee partners, and doing it at a volume that creates an appreciable community of local development actors in a country so that they can bring good ideas that were formerly being parachuted in from DC or Brussels.” Done well, the work of community mobilization requires intensive attention to recruitment, training, and team building, and therefore requires funding. Investing in community mobilization builds the foundation for long-term, systemic change, supporting communities in effecting change for themselves.

Government partnership. Government spending on social and environmental issues can make philanthropy’s contribution look minuscule in comparison. So why invest in or partner with government? The compelling opportunity here is for donors to invest in government experiments or innovations that, in the normal course of business, government could not fund themselves. This in turn can lead to major systems change as government is such a critical part of almost any system.

A Learning Journey

“The work of systems change,” says van Oranje from Girls Not Brides, “is about working in an iterative fashion. Do your homework well, but don’t wait until you have all the answers. Learn by doing.”

For those donors seeking help on this learning journey, there are an increasing number of donor circles and donor support organizations engaged in creating opportunities for donors to go deeper into systems change. These include Synergos, The Philanthropy Workshop, Co-Impact, and Social Impact Exchange.

Systems change might feel like a leap for many donors. However, as existing institutions and ways of supporting society’s well-being continue to break down, systems change is becoming a larger part of how some philanthropists are contributing to improving society and the planet. As the saying goes, “The only way to it is through it.”

John Kania

John Kania is the executive director of the Collective Change Lab, focusing on developing field level insights into the practice of systems change. He was previously global managing director of nonprofit consulting firm FSG, where he continues to serve as a member of the board of directors.

Cynthia Rayner

Cynthia Rayner is a researcher, writer, and lecturer affiliated with the Collective Change Lab and the Bertha Centre for Social Innovation at the University of Cape Town Graduate School of Business. She is also the co-author of “The Systems Work of Social Change,” published by Oxford University Press.

This article was originally published in Social Investor magazine, a publication by Chandler Foundation looking at the challenges of social impact, featuring insights from a diverse range of social change leaders.

Comments (0)