COP28 paved the way for a consensus-built commitment to transition away from fossil fuels. However, the implementation and pathways for the transition will be complex and require responsible and equitable management.

Philanthropy can help facilitate a transition to climate-compatible growth, including in many low-income countries that are dependent on fossil fuels. Achieving this transition requires a nuanced understanding of the diverse challenges across countries and communities.

To support low-carbon climate solutions without hindering development, philanthropy should take a multifaceted approach that accounts for economic, social, political, and technical considerations.

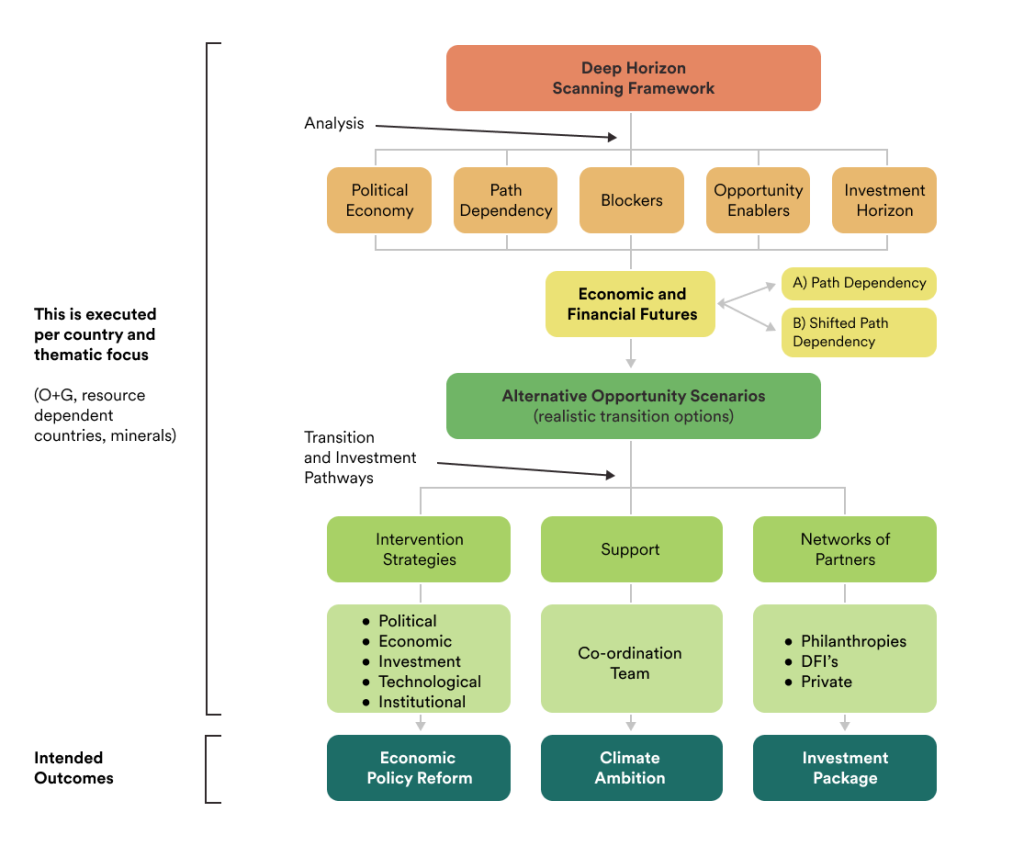

Broadly, we suggest an approach that includes four potential workstreams (see Figure 1):

Analytical framework:

A thorough analytical framework is essential for guiding philanthropic interventions. This involves examining the political economy of a given issue area or region, understanding dependencies, acknowledging path dependencies that may hinder change, addressing blockers, and identifying enablers that can incentivize positive change. Additionally, it is crucial to consider the investment horizon for the transition process, as timing can either impede or facilitate pathways for change.

Futures exploration:

Informed decision-making requires anticipating various future scenarios — from shocks that shift the world into a state of emergency to positive opportunities to advance a more just, equitable, and sustainable global economy. By scanning the horizon for signals of change, philanthropy and other actors can assess the potential developments in finance, economy, and politics at both local and global levels. This exploration can help identify emerging trends, assess their potential impacts on climate solutions, and inform the development of alternative opportunity scenarios.

Implementation:

Designing and implementing effective solutions require comprehensive intervention strategies that address institutional, political, technical, and economic reforms. Driving meaningful change requires capacity support and partnerships across philanthropic, private, and public sectors. Adopting such strategies can help maximize the effectiveness of philanthropic efforts and ensure they contribute to a just and equitable transition toward a climate-compatible future.

Displacement equivalent:

The achievability of meaningful transitions away from fossil fuels depends on the depth of economic transformation and diversification. These transitions take time and may not be achieved by all countries. Any alternatives to fossil fuels must be substantive and offer comparable or greater economic benefits such as jobs, exports, and tax incentives. New technology and knowledge could further expand the depth of the economic transition process.

Applying a framework for assessing transition pathways

Philanthropy can apply this framework to various challenges, such as support for transitioning away from natural gas or growing value-added local manufacturing (e.g. processing capacity and localizing supply chains) in extracting critical minerals. The potential pathways uncovered by this approach could have major resource implications for economic growth and climate goals.

Studies from the African Climate Foundation (ACF) on emerging gas producers show that if we do not adhere to a 1.5° C goal, fossil fuels such as gas will continue to be in demand. Both emerging producers and more mature producers are likely to supply the global economy, especially given rising demand in Asia.

If the world does move more strongly towards a 1.5° C pathway and meet 2030 goals and net zero by 2050, new and emerging producer countries like Tanzania and Mozambique will likely build assets that could be stranded. These countries are also likely not to be the least cost producers. Hence, if they do not diversify their economies – which they have a significant potential to do – they risk not moving their economies out of a poverty trap.

In the case study for Tanzania and Mozambique, possible pathways to transition away from gas were explored, including assessing international investor commitments, evaluating the economic viability of proposed resources, addressing fiscal and commercial uncertainties in the local market, and navigating political dynamics.

The alternate economic pathways with renewables or other zero-carbon energy were not fully available to inform decision-making, nor were the social and economic impacts from this transition fully available. This was partly due to limited capacity, models, and data to support a broad energy and economic feasibility study to analyze the potential outcomes of a zero-carbon transition pathway.

Further work is needed for countries like Mozambique and Tanzania to understand how the initial phase of gas exports that could generate revenue may be initially used to diversify the economy. A more robust economic transition plan should be offered to demonstrate that these countries do not need to find themselves in a resource curse trap, which may only be possible if they act soon to diversify and use the revenues from natural resource exploitation to transition to more resilient and low-carbon economies.

The amount of time needed to conduct such studies can impede timely interventions that delay investment decisions, affecting energy resource development and further hindering growth. Often, local capacity does not exist; however, reliance on external consultants may contribute to hasty decisions that fail to meet local communities’ economic needs and concerns.

Informed transition pathways must consider the cost and benefits of maintaining the status quo — or shifting to a new set of investments and asset classes that minimize exposure to fossil fuel dependency over time. These pathways must also account for how such a decision may affect local communities, workers, and a just and responsible transition.

A collaborative structure for the green transition

A global green transition would require investments in trillions of dollars per year. This level of investment would keep the Paris Agreement’s 1.5° C within reach and help avoid the possibility of an overshoot that could unleash irreversible climate tipping points.

Now is the time to accelerate collaborative efforts to speed up private, public, and philanthropic partnerships (PPPPs), such as the World Economic Forum’s Giving to Amplify Earth’s Action initiative. In recent years, PPPPs have evolved with new approaches such as country platform models — for example, the Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JETPs) in South Africa, Indonesia, Senegal, and Vietnam. Such platforms can be expanded to other types of climate investments such as energy efficiency, forest protection, mobility, and agriculture.

Currently, only a small percentage of philanthropic funding goes to climate change mitigation efforts, though it can have an outsized impact through the power of strategic collaboration.

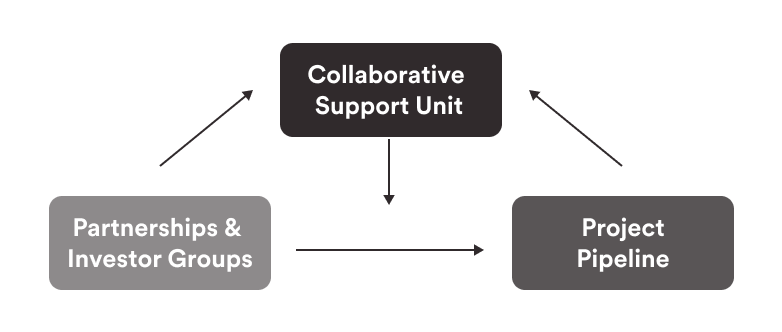

Philanthropy can enable a collaborative structure that helps identify and access the needed public, private, and philanthropic capital (Figure 2). This structure can also help investor groups assess how they may deploy capital most efficiently and transition their own financing to low-carbon assets to avoid longer-term risks of stranded fossil assets.

Figure 2: A collaborative structure for the energy transition

Projects that require financing to expand energy resources for economic growth require understanding the full implications of choosing low-carbon solutions versus fossil-based fuels. This involves carefully developing supporting analyses that fully consider the potential economic and climate-compatible pathways and futures based on the previously discussed framework. A new collaborative support unit can help accelerate matchmaking process by screening the project pipeline, vetting potential pathways through newly developed, open-sourced country-based analytical tools, and helping build networks and partnerships with financial institutes that provide the funding or investments.

Philanthropic support has already helped establish collaborative entities like the Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance and Allied Climate Partners that will advance responsible transitions. These entities must expand rapidly to meet the growing needs of many countries that need a viable pathway to transition.

Pathways to a low-carbon future

Philanthropy can and must play a transformative role in supporting responsible and climate-compatible transitions away from fossil fuels, particularly in emerging economies seeking to balance decarbonization with economic growth. To do so, philanthropy should strategically invest resources and use a comprehensive framework that considers the local contexts and challenges of communities, political leaders, and policymakers. These efforts can help rapidly accelerate progress toward both a low-carbon future and economic development.

Surabi Menon, a leading climate scientist and vice president of Global Intelligence at ClimateWorks Foundation, was the executive director of partnerships for COP28 UAE.

Saliem Fakir is executive director of the African Climate Foundation, the first African-led strategic grant maker working at the nexus of climate change and development.

Comments (0)