For hundreds of thousands of women and babies around the world, health disparities continue to cause too many tragic and preventable deaths each year. The Sustainable Development Goals challenge us to reduce global maternal mortality to less than 70 per 100,000 live births (it was 211 in 2017) and to reduce preventable deaths of newborns to at least 12 per 1,000 live births (17 in 2019) by 2030.

Photo courtesy of Equalize Health.

Progress in recent years has seen us steadily stay on track to meet these goals, but the consequences of Covid-19 now threaten to reverse this trend. With less than 10 years left to reach these targets, the necessity to focus our partnerships and resources on the right innovations in order to accelerate progress, is even more critical.

To help identify recommendations, Equalize Health (formerly D-Rev) recently undertook a study investigating: How much funding has been invested in maternal and newborn health (MNH) innovation? Which key social investment strategies in MNH produce results, and why?

How much funding has been invested in maternal and newborn health (MNH) innovation?

We partnered with Results for Development, who lead the management for Global Innovation Exchange (GIE), one of the largest databases of development innovations and funding, with funders such as USAID, Grand Challenges Canada, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and Expo 2020 providing data. Our research was led by Allison Ettenger, a researcher with diverse experience in global health innovation including at an Kenyan social enterprise and an international development non-profit think tank.

In analysing the essential characteristics of MNH innovation funding from 2008 to 2019 in late 2020, we found that:

- Twenty-eight per cent, or around $200 million, of the global health funding was focused on MNH (457 innovations). Note: the GIE data does not include NEST 360 funds which is the equivalent of around 40 per cent of all GIE-tracked newborn global health funding in the last 12 years.

- A majority (around 40 per cent) of MNH investment is made in early stage innovations ($72.7 million out of $200 million).

- Universities are the most common recipient of funding (46 percent of funding or $90.7 million) for both maternal and newborn innovations.

Which key social investment strategies in MNH produce results, and why?

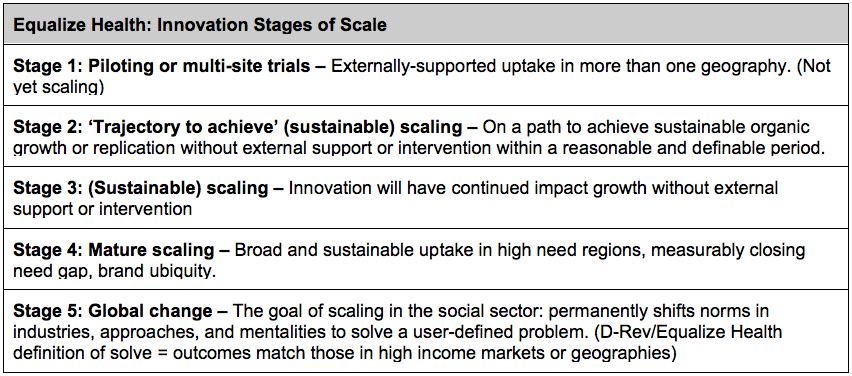

Two-fifths of innovations were classified as ‘closed’ or ‘unknown’, because the project had ended or there was no evidence of continued work. Analysis of the other MNH innovations indicated that approximately fiver per cent reached Stage 3 or higher, meaning they had attained sustainable impact. None were led by academic institutions. This makes intuitive sense: universities are incentivised to do research, publish and educate, not fully develop ideas into innovations built for scale and sustainability. These later stage (‘proven’) innovations represented only 10 per cent ($32.5 million) of all MNH innovation funding. Our key takeaway was that current MNH funding strategies do not appear aligned with accelerating results.

Accelerating Results

We therefore recommend that funders of MNH innovation shift focus to the later stages of innovation. As we have relied on academia to carry the weight for research, we must now identify the key innovators who are best positioned and structured to take concepts through implementation to reach wide-scale, sustained adoption of proven innovations. The data set suggested these innovators were NGOs and for-profit companies.

We recommend the following to accelerate progress to MNH health targets by 2030.

- Fund innovators who are positioned to execute against goals. The GIE data showed that there is a misalignment with the majority of funding going to academia, who are strong at early stage research and discovery, but not positioned or incentivised to take innovations to impact.

- Prioritise market-based and other solutions that are designed for sustainable scale. The number of innovations that reach the market at any level of impact are small, much lower than comparable for-profit health investments. Market-based solutions promote accountability and local ownership because scaling only happens when customers – who are also ‘beneficiaries’ – choose the innovation.

- Define scale so innovators are driving innovation to impact, not midway points like market launch: Funders and practitioners need to come together to better define scale, its characteristics (e.g. sustainable funding model), and what success looks like so that we can concentrate funds where we stand the best chance of accelerating results. In doing this analysis, we developed a tiered definition of scale based on sustainable impact.

- Strengthen accountability and share the knowledge: Further analysis of how the funding has changed over the years could offer greater lessons around what works and what doesn’t. We encourage key donors in the MNH sector to continue supporting and analysing GIE and other data sets so our sector can continue to learn from our successes and ‘failures’. Our hope is that a culture of continuous analysis and reflection will lead to greater sharing of learnings and best practices for philanthropists and social investors.

- Increase funding at the right stage: When we identify the key organisations and partnerships that are positioned to take innovations to implementation and scale, we need to invest the funds necessary. The data suggested that most investments were early stage, and while that is needed, there is a higher impact and cost efficiency in supporting mezzanine innovators who have built models and organisations. Later stage projects offer an significant opportunity for funders, and more global collaborations and pooled funds could accelerate results.

The full data analysis can be found at equalizehealth.org. We gratefully acknowledge the use of GIE’s database and their contributions as well as the work of Allison Ettenger, Sarah Darmstadt, and Sweta Govani.

Krista Donaldson is CEO of Equalize Health, and Stephanie Heckman is Director of Partnerships at Equalize Health.

Upcoming issue: Global health philanthropy

Subscribe today to make sure not to miss it!

At £46 billion each year – almost a quarter of all grantmaking – philanthropy spends more on health-related causes than anything else. As the Covid-19 pandemic intensified, philanthropy provided critical funding for vaccine development, medical equipment, mutual aid, social welfare, and global health infrastructure. But there is intense debate about how the largest foundations interact with governments, international bodies and pharmaceutical companies and how they should be held accountable to citizens. This issue of Alliance considers new directions for global health philanthropy and explores whether health funding is going where its most needed. It is guest edited by Julia Greenberg, Director, Governance and Financing, Public Health program, Open Society Foundations and Aggrey Aluso, Manager of Health and Rights Program, Open Society Initiative for Eastern Africa.

Comments (0)