As we write this, the world is reeling from a calamitous health and economic crisis due to COVID-19. Infection numbers continue to climb, as is, tragically, the death toll from the disease. The economic impacts are already severe and far-reaching, and things will likely get worse before they get better – according to the International Monetary Fund, this pandemic will result in the worst economic recession since the Great Depression.

In the midst of this crisis, when so much attention is rightly focused on responding to immediate needs, some voices are also calling for us to seize this opportunity to ‘rebuild better’ across a range of areas, from better conditions for lower-paid workers, to more resilient food systems. As the saying goes, we should never let a crisis go to waste. But how exactly are we meant to do that?

In 2017, we took a deep dive into the question of how markets become more inclusive and sustainable, in partnership with the Rockefeller Foundation. We looked into history to see where radical shifts had been achieved, and worked to understand how they had happened. As expected, our analysis showed that breakthrough business innovations and visionary leadership played a key part.

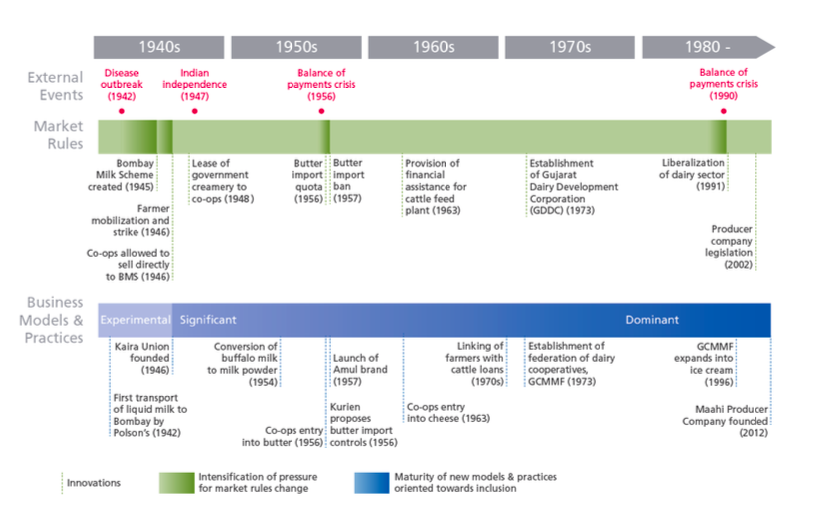

However, we also found that critical steps in these market transformations were often precipitated by economic and political crises. The Great Depression paved the way for the rise of smallholder coffee in Colombia, now a decades-long export success story. In the Philippines of the 1980s, political revolution and then an electricity crisis helped set the stage for a much more inclusive water market in Manila. In India, we found that key advances in the success of Gujarat dairy—where over 3 million smallholder dairy farmers own the country’s largest food products company—could be traced back to a major disease outbreak, the independence struggle, and not one but two currency crises.

Of course, a crisis offers no guarantee of any positive change. The hope and optimism around the Arab Spring of the early 2010s have largely not been converted into actual progress; instead, most of the countries involved have actually seen greater conflict and instability in the years since.

What a crisis can do is help create a window of opportunity for change; what we then do with that window is the key to making progress. Across our case study research, we saw a critical interplay between innovations in business models and practices, and those around market rules—this combination opened windows of opportunity and drove lasting change.

The timeline from our Gujarat dairy analysis illustrates this point (see graphic), showing the diversity of innovations that can play a role in catalysing change. Market rules changes were enabled not only by public policy decisions, but also by farmer mobilisation and direct action, which intensified political pressure for change. Meanwhile, these would not have been consequential without the corresponding technological and business innovations that allowed the farmer cooperatives to exploit newly favourable market rules.

As the economist Daron Acemoglu and political scientist James Robinson have noted, crises can be critical junctures in the evolution of our societies, and there is every possibility that COVID-19 will prove this to be true. However, the direction of change is not yet determined, and therein lies both danger and opportunity. Consider the situation of the essential workers who have been more prominent in the public discourse in recent months: will the crisis reduce job opportunity and security resulting from employers pushing for greater flexibility and automation, or will greater public regard for these workers spur moves to improve pay, conditions and job roles?

Those of us who want to see a fairer and more sustainable world must not let this crisis pass us by. We cannot wait for immediate needs to be addressed before we turn to the challenge of rebuilding—we must find ways to do both, especially as this crisis will not be over anytime soon. In our next blog, we will share a number of key lessons for how philanthropic actors could approach the challenge of leveraging this crisis to ‘rebuild better’, drawn from our experience of working with partners over the past few years to make markets more inclusive.

Harvey Koh is a Managing Director at FSG, and Laura Amaya is an Associate Director at FSG based in London. Thanks to the Rockefeller Foundation for their support of the work described in this article.

Read If this crisis is an opportunity, how do we seize it – Part 2

Comments (0)