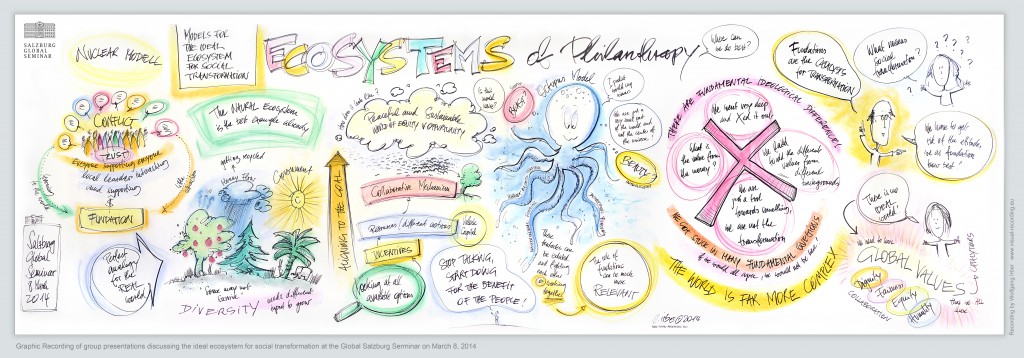

Ecosystems are complex. They incorporate living organisms like plants, non-living components such as water, and the complex interactions between these different elements which have varying impacts upon each other. Removal or expansion of one part of an ecosystem can have a deep impact on others; small tweaks or introductions of new elements can have long-term, unexpected (and possibly unwanted) consequences. If we were to imagine the ‘ecosystem’ of philanthropy for social change – also arguably a complex system – what would we see? A simple flow chart? A forest? An octopus?! (Yes, an octopus – read on…)

In March 2014, Salzburg Global Seminar and Hivos convened 45 experts from philanthropy, finance, international policy, research and social activism to examine urgent questions related to channelling more money towards social transformation in ways that maximize the positive impact of the funds. The programme was heavily influenced by a 2013 article by Michael Edwards, ‘Beauty and the Beast: Can money ever foster social transformation?’, which examined the deep ambivalence evident in the philanthropic and aid sectors about money, power and social change. In the article, Edwards explores how money is both ‘a curse and a cure’ in regard to social change and posits that a more balanced funding ecosystem is vital for tackling root causes of poverty and inequality.

The Salzburg participants were asked to expand their (eco)systems thinking beyond philanthropic funding per se and identify core elements of a healthier and more balanced ecosystem that could enable and support social transformation.

A simple flow chart?

Just as the participants came from many different backgrounds from across the philanthropic spectrum, so too were the ecosystem models distinct and varied.

One could see the system of philanthropy for social change in the form of a flow chart, with funds flowing into different mechanisms that align and work together to the same goal. But given the complexity of ecosystems – including that of philanthropy for social change – some in Salzburg considered this overly simplistic.

A beautiful and beastly octopus?

Some of the participants were inspired to envision philanthropy for social change as an octopus with the potential to be both beautiful and beastly, the tentacles representing the multiple forms of funding available to support social change: foundations, market-based philanthropy, impact investing, government aid, etc.

Currently, each ‘tentacle’ acts relatively independently of the others; tentacles may be unaware of what the others are doing or even fighting each other, pulling in different directions. An octopus has the ability both to adapt to and to obscure its surroundings. Highly intelligent and well-meaning at first sight, it can move unexpectedly and act ruthlessly. If the octopus’s tentacles continue to pull in different directions, the whole animal (representing the progress of social change) will remain confused and ineffectual. But if the values of deep social transformation can be absorbed into its central intelligence system, there is a chance that the octopus can ‘tame’ its tentacles, apply its considerable skills for good, and advance social change. Only when the octopus’s tentacles work in concert can the beautiful beast move forward and in turn have a positive impact on its surroundings.

Admittedly, the octopus in itself is not an ecosystem; it remains a small creature in the vast ocean of global finance. But it can have more effect on its surroundings than its size would otherwise suggest – an analogy many in Salzburg felt apt for philanthropy for social change.

Or a forest?

One could build a more expansive vision of the ecosystem of philanthropy by imagining one of the most complex natural ecosystems: a forest.

Forests have a diversity of vegetation, and diversity is also vital for social change: towering trees ̶ long-term programmes that run for decades and are not cut down or expected to offer a ‘return on investment’ (ROI) before reaching maturation; mid-canopy trees that do not have as long life spans but are given time to grow before being harvested, providing ROI; and young seedlings that have only just been planted or sprung from the fruits of other efforts.

The programmes are also of varying ‘species’: single-issue programmes that grow independently of the surrounding plants; wide-ranging programmes with branches that help prop up other organizations, providing fruit that produces other trees and offering leafy nourishment (advice and experience) to saplings (but there is a risk they grow too large and absorb the funds or obscure the work of their smaller counterparts); and vines that cling to larger programmes. There are the ‘evergreen’ programmes that run continually, and those that lie dormant before springing back into action at the appropriate time.

Nourishing the forest

All these trees need nourishment, and here water is money. Without the rain/money, programmes can shrivel and die; but an unexpected deluge can have a negative impact, with programmes unable to respond quickly enough to make best use of the funds and at risk of being drowned out. Some plants need more water than others; some conserve and store water better than others; some transpire moisture (money) back into the atmosphere to be recycled and rained down again elsewhere (ie impact investing). Besides water, the programmes/trees need nourishment from the sun – in this scenario, the government. The sun helps photosynthesis, enabling programmes to be successful with supportive legislation; it can also be overbearing, so hot and inhospitable it withers the forest.

As in a real forest, not all these trees will survive. In addition to well-funded ‘healthy’ programmes, the forest is also home to deadwood – programmes that have been part-funded but abandoned or unsuccessful – and quick-growing trees that are expected to produce a speedy return before they’ve had a chance to leaf properly.

After all, this forest of programmes has been planted by different people, at different times and for different purposes. Some will be planted by small NGOs and watered by teams of crowdfunders; some will be planted by large foundations that regularly ‘rain money’ but leave the arboriculture to the NGOs; some are planted with the expectation of producing fruit that will produce other programmes. Some programmes will prove to be ‘invasive species’ (often planted by well-meaning but misdirected or mistrusted donors), planted in areas that do not want or need them, possibly displacing community-appropriate programmes or other natural inhabitants.

It is also possible that some sources or forms of funding might have the same effect as acid rain – stripping the foliage and poisoning the soil, limiting its capacity to produce positive social change.

Despite these analogies, questions still abound. For the octopus, how should the values of social transformation be fed into it and by whom? If the multiple tentacles cannot be ‘tamed’, can we afford to cut one off and allow something else to grow in its place? In the forest, if money is rain, where did the water come from in the first place? How do we introduce more money into the system in a healthy, sustainable manner? And how can we be sure that the programmes we plant and nourish are contributing to social transformation and not just superficial, short-term change? How do we measure our value as philanthropists?

The role of philanthropy in supporting transformation

The Salzburg–Hivos programme was intended to extend current thinking and catalyse new thinking about the role of philanthropy in supporting transformation, and the role of money in particular. Edwards’ paper contends that the current funding ‘system’ for social transformation is out of balance: too much emphasis is placed on, and too many resources channelled to, a few select approaches while others –arguably those that are more ‘democratic’ in nature, and in which ‘success’ is less tied to financial/market outcomes – are increasingly eschewed.

Identifying the core elements of a healthy system may help us to increase the ability of philanthropy, and money in particular, to support social transformation, and help the diverse – and sometimes divisive – actors and approaches to understand how they can work together more effectively towards shared goals.

Louise Hallman is the editor at Salzburg Global Seminar. Emaillhallman@salzburgglobal.org

Nancy R Smith is an independent philanthropy and non-profit consultant. Emailnrs.austria@gmail.com

Comments (0)