Women are unduly affected by environmental degradation. They walk further when wells run dry or firewood is scarce. They work harder for less when extreme weather devastates crops. They tend to suffer more from climate change, other environmental disasters and resource-related migration. And yet, or perhaps as a result, women have proven themselves to be remarkable stewards and protectors of their environments. To me, the case for an environmental funder to introduce a specific grantmaking strand focused on women seems clear. Even among my colleagues, however, not everyone agrees with me.

The journey of the Global Greengrants Fund towards integrating a gender perspective in our funding is a work in progress that has been rough and uneven. But in honestly describing the challenges and successes we are experiencing in the journey, I hope to support other grantmakers in their efforts to improve their funding.

Initially, Greengrants’ focus was environmental, on what some might term conservation. Over time, with the influence of advisers, the funding has moved more toward the intersection of human rights and the environment. Greengrants funds a wide diversity of issues and populations. The health of the planet is inextricably linked with that of the people who receive the bulk of our support: indigenous, poor and underrepresented, rural and forest-dependent, and women.

Greengrants’ new mission is to mobilize resources for environmental sustainability and social justice. We believe positive social change comes from the ground up. It is more likely to be lasting when called for by community leaders, defined by the people who are most affected, and pursued by local groups.

Just a variable in the database

Until recently, ‘women and the environment’ has not been an explicit programme area at Greengrants. None of our boards had chosen to focus on funding women as a grantmaking strategy. ‘Women’ was a variable in our database, but until I came on the scene in 2009, we were not using it to track our funding.

When we started counting, I found the results troubling. In 2009/10, only 122 grants were specifically dedicated to investing in women. Some 309 went to defend water and water rights; 214 to protect biodiversity; 192 to support indigenous people’s projects; 185 specifically to fight climate change; and 169 to tackle hunger and food security. While we might claim that most grants have benefited women, the overall percentage of grants made to support women-specific environmental projects was low compared to other categories.

Around the world, half our advisers are women, although in some regions they are primarily men. Organized into boards, advisers are charged with designing regional, or decentralized, strategies, recommending projects for funding, and mentoring and monitoring grantees. Advisers have been recruited because they are active in environmental causes and involved in social movements. They come from all walks of life, and have a range of perspectives. Of course, being a woman does not necessarily lead to a clear analysis of the link between women’s lives and the environment, just as being a man does not indicate sexism.

Advisers have recommended funding to women’s co-ops, such as the Casa del Maiz project that created sustainable livelihoods for young women in northern Nicaragua, and to women-led environmental health initiatives, such as the doctors who educated mothers in Yakutsk, Russia about the dangers of contaminated drinking water.

Imposing a ‘top-down’ strategy on a ‘bottom-up’ organization

Early in my tenure, I told a former employee and consultant helping to coordinate a visit with East African groups that I specifically wanted to see women-led projects. ‘That’s not what we fund,’ he told me. I wondered if this was the view held by the advisers in the region, or his alone. Grantee visits on that trip included a thriving women’s cooperative.

I am committed to adding a gender lens to the funding process at Greengrants. To me, it seems an obvious need, but it’s a tricky proposition as we depend on and trust our advisers to help us understand the local context and make recommendations regarding grantmaking. Whatever their gender, Greengrants’ advisers have mixed opinions about the need to include a women’s perspective in strategy development and grantmaking.

I am asked: what is my rationale for imposing top-down change in a bottom-up organization? My answer is: how can we implement a social justice mission without a gender lens?

I have attempted to put my convictions into operation in a variety of ways, but it has been a challenge. In order to help me think this through, I went to an institute on the subject offered by the Gender and Global Grantmaking Initiative of Grantmakers without Borders. I have encouraged advisers and staff to attend. This summer, I participated in a higher-level strategy session of the same group.

The gender continuum

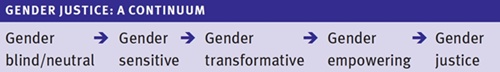

The main objective of integrating gender into our grantmaking is to support organizations, projects, programmes and policy that fall on ‘the gendered grantmaking continuum’.[1] A gender-neutral approach, at one end of the spectrum, does not reinforce existing gender inequalities. It does no harm. Most of Greengrants’ funding falls in this category. A gender-sensitive funding strategy recognizes existing gender inequalities. Moving up the spectrum, gender-positive or transformative grantmaking can help empower communities to take action to claim their rights. We have made grants in this category. What I hope to realize, however, is a gender justice analysis, with funding that can move toward a structural change in gender relations.

Gender justice: a continuum

Within six months of coming to Greengrants, I visited Kavita Ramdas, then president of the Global Fund for Women. We agreed to begin organizing programmes together on the topic of women and the environment at funder affinity meetings. To date, we have held successful panels on the topic at the International Human Rights Funders Group conference and the Environmental Grantmakers Association. While the audience was mixed at IHRFG, where gender is understood as part of a human rights framework, only women attended the EGA session, reinforcing a disturbing stereotype about environmental funders.

This is work in the field, but what about the organization I lead?

Making the case and overcoming resistance

I invited a sociologist from the University of Colorado to do an in-service training with the Boulder staff on women and the environment, one of her specialities. She made an excellent case for focusing on women-run and women-engaged projects. Where women are doing well, so is the environment; where the environment is healthy, women’s, men’s and children’s lives are better. The staff seemed interested, but I sensed a lack of understanding regarding the need to integrate a gender lens into our work.

There is varying opinion from our advisory network. In a recent conversation with a Latin American adviser, he made the argument that ‘cultural differences, particularly in indigenous communities, create complications when applying a gender lens. We need to be sensitive to the realities on the ground. Grantmaking with a gender lens is something many of us already do, but in a way that is most productive to the movement and its beneficiaries.’

I agree that we need to be sensitive and understand realities on the ground. But we could be funding more indigenous women’s groups and women leaders. It is challenging to mandate, and I have not imposed a cover-all policy, but I have begun working on a board-by-board basis.

Our India advisory board has recently decided that funding women’s issues is an integral part of their strategy. In the past, most grant rounds have included proposals focusing on either women’s issues or environmental groups that work with women. In addition, many proposals include a women-focused component. The India advisers try to be aware of instances where even though the presence of women is natural in the project, women may not be at the forefront of managing the work. In such instances they believe this should be drawn to the notice of grantees and changes requested. Another productive approach may be to help these groups connect with other such organizations which may be more experienced in the area.

The conversations continue and I am optimistic. My hope is to increase understanding about the deep value of gender-positive grantmaking among our network. Advisers are our trusted experts, our eyes and ears on the ground. Perhaps with more information and dialogue, more of them will want to adopt a gender lens.

But this isn’t just about Greengrants. I believe the issue is prevalent in the wider funding world – and in society at large – and it’s an issue that needs to be tackled.

1 Adapted and elaborated by Linksbridge for the gender and grantmaking workshops. The original source of the continuum was developed in the reproductive health sector (particularly referencing work by Anne Eckman).

Terry Odendahl is executive director and CEO of the Global Greengrants Fund. Email terry@greengrants.org

Global Greengrants Fund

GGF channels small grants to grassroots groups taking action to achieve clean environments, sustainable livelihoods, healthy communities and human rights around the world. Grantmaking is directed by local activists who are deeply knowledgeable about the issues and groups that need support. Over the course of an 18-year history, GGF has made more than 6,500 grants in 141 countries.

Comments (0)