Violence against women (VAW) is a widespread human rights violation across the world, including Europe. In the EU, one in three women from age 15 onwards has experienced physical and/or sexual violence (one in five of those by a partner), and less than 15 per cent of them contacted the police. More than half of women in Europe have experienced sexual harassment, and also more than half have avoided places or situations for fear of being physically or sexually assaulted.

On the day of the release of these survey results by the EU Fundamental Rights Agency in 2014, members of Ariadne, the European Human Rights Funders network gathered to discuss the response of philanthropy to violence against women in Europe. As the data showed the enormity of the issue, the group discussed what needed to happen in order to respond to this human rights crisis.

In a way, the fact that it took until the second decade of the 21st century to generate Europe-wide data on the prevalence of violence against women, was indicative that the issue had been neglected – “what is not counted doesn’t count”. And this even despite the fact that the cost of violence against women was calculated to amount to a staggering € 226 billion annually in the EU, and despite research that showed that increasing spending on prevention of domestic violence in the EU by one Euro, 87 Euros of costs related to this violence could be saved. In many ways, violence against women seems to have been the elephant in the room that was ignored when decisions about public policies and philanthropic programmes were made.

Istanbul Convention

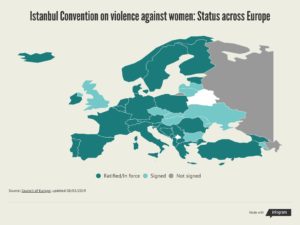

There have been policy advances at the international and national level, recognising violence against women as a human rights violation, thanks to tireless feminist activism over decades. In August 2014, the Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence entered into force. Known as the Istanbul Convention, it is a ground breaking human rights instrument that is considered a gold standard for tackling violence against women. The Istanbul Convention both acknowledges and addresses violence against women as a cause and consequence of gender inequality. As it has been ratified by a considerable number of countries across Europe (34 to date), we are today in a setting where governments have committed to put in place the structures and funding necessary for an integrated policy framework that can effectively provide comprehensive measures for prevention, support for survivors and ensuring that perpetrators are held to account.

There have also been further political challenges, as the issue of violence against women has been increasingly mis-used to advance an anti-migration, racist agenda

Conservative backlash

However, NGOs across Europe report that implementation at national level lags behind. Moreover, we have even seen a conservative backlash against the Istanbul Convention, where false claims about the content of the Convention are used to mobilise against ratification and implementation in some countries, such as Bulgaria and Croatia.

There have also been further political challenges, as the issue of violence against women has been increasingly mis-used to advance an anti-migration, racist agenda: certain groups claim that they want to protect women from violence, but their proposed solutions are limited to the deportation of foreigners, and the focus is on the protection of white, European women from foreign men. The events in Cologne on New Year’s Eve 2015/16 and the discourse that followed were a highly visible example of this. In the context of these events, it also became apparent that organisations that work on ending violence against women were not equipped to provide a timely and strategic communications response. The initial narrative around the events was defined mainly by right wing populist voices.

Spotlight on European philanthropy and violence

In 2016, Ariadne addressed these issues at its annual meeting, and this led to Paris-based philanthropy consultant, Karen Weisblatt and myself, supported by a small advisory group of Ariadne members, starting exploratory research on philanthropic engagement with ending violence against women.

We found out that only few donors were funding work on violence against women in Europe – a third of respondents to our survey said that they fund this work in Europe, two-thirds in the Global South. These few generally had small annual budgets and provided short-term funding, which meant that most NGOs in this field received a limited number of grants, covering only a few years.

Funding work to end violence against women is possibly a prime example of feminist philanthropy, as it addresses the core issue of a harmful patriarchal societal structure.

In our survey, the NGOs responded that they needed sustained, long-term and flexible funding in order to do their work effectively. They also told us that they would like to do more advocacy if they could access funding for this work. This will come as no surprise, since ending violence against women requires a long-term approach, as it involves changing not only laws, but deeply ingrained attitudes and practices. It won’t happen overnight and requires the building of alliances across issues, and a critical mass. If they are to actively bring their voices to the movement against racism, they need resources for this work too. More donors need to fund in a way that acknowledges the relevance of ending violence against women in a broader social justice context. One notable example is the UK’s Esmée Fairbairn Foundation. Without having a separate programme on the issue, they have provided significant funding for work that aims at ending VAW in the context of their programmes on systemic change, and through their children and young people programmes.

Currently, even many of the initiatives aimed at promoting gender equality don’t address violence against women. Yet violence against women is ‘the mother issue’ of all efforts for gender equality. It is “the methodology that sustains patriarchy” as author and activist Eve Ensler once put it. But rather than being recognised and addressed as such, it too often remains the elephant in the room in other programmes designed to advance gender equality.

Enter feminist philanthropy

This neglect makes a feminist approach all the more important. Funding work to end violence against women is possibly a prime example of feminist philanthropy, as it addresses the core issue of a harmful patriarchal societal structure. Recognising the deeply rooted and intersectional nature of patriarchal violence, an explicitly feminist philanthropy agenda is best placed to address it in a sustainable manner.

Whilst foundations could (and should) not provide all the resources for the work that is necessary to end VAW, they could have a big leverage effect by providing the kind of funding that enables groups to advocate effectively to ensure that their governments take responsibility in their policies, and that they live up to the commitments they have already made.

In recent years, we have seen some positive developments, on both sides of the Atlantic. In particular, the social movement #metoo has brought the issue to the fore and mobilised new allies.

In the US, TIME’S UP, an initiative led by prominent personalities within the film industry, has raised over $22 million for a Legal Defense Fund to support women who have experienced sexual harassment at work. NoVo Foundation, OSF, Ford Foundation and others have joined forces to create the Collaborative for Women’s Safety and Dignity. Melinda Gates recently committed to investing $1 billion to advance gender equality in the US, and ending sexual harassment and discrimination in the workplace is part of her 10-year strategy.

In the UK, TIME’S UP UK joined forces with Rosa, the UK fund for women and girls, and raised around £3 million for the Justice and Equality Fund, which ‘aims to bring an end to the culture of harassment, abuse and impunity by resourcing an expert network of advice, support and advocacy organisations and projects.’ The development of the programme and the grantmaking process were highly participatory, involving different donors and activists / grantee partners.

The issue of sexual harassment at the work place has also been addressed within the development aid sector (#aidtoo), and eventually also in the philanthropic community in Europe. Ariadne established an internal working group on the topic, conducted a survey of members and followed up with the report Preventing and responding to sexual harassment: Funders’ practices and challenges. In Germany, Bundesverband Deutscher Stiftungen has established, through a partnership with Charité Berlin, a confidential contact point for its members.

In France, philanthropy and a public institution partnered for research on funding for efforts to end VAW. In September 2019, the French government announced a significant commitment, including additional funding, to ending violence against women, in particular intimate partner violence.

In Germany, Dreilinden’s Ise Bosch has been a committed champion for the issue among the country’s philanthropic community, for example by making it a topic and call to action in her acceptance speech of the “German philanthropist of the year” award in 2018. Ise has also supported the work done by the Criterion Institute around engaging impact investing finance to end VAW.

At the end of the day we need to ask ourselves how willing we are to continue to accept the elephant in the room: that one in three women in Europe and worldwide experience violence, and most never see the perpetrator held to account.

With the growing understanding and evidence of the magnitude of violence against women and of approaches to address it, what can we observe about philanthropy’s role? What does a feminist philanthropic approach to ending VAW look like?

First, it acknowledges that ending VAW is a precondition to any other work that aims to promote gender equality, that it needs to be considered in an intersectional way, and that considering it as an integral part can have an accelerator effect to the broader social justice and human rights agenda.

It acknowledges the magnitude of the issue on our doorstep, in Europe, including in our own institutions, and takes a zero tolerance approach to violence against women, including among staff and boards, as well as grantees and partners.

It acknowledges the complexity of the issue: there is no quick fix and it needs a long-term, collective approach. If we want to be successful, we need to address its multiple dimensions, and we can do this best when we share knowledge and collaborate.

Most importantly: it will start by listening to those involved and develop its strategies based on what it learns, as NoVo Foundation has done for the design and implementation of its Move to End Violence programme, which will feature in Alliance’s December issue on feminist philanthropy.

At the end of the day we need to ask ourselves how willing we are to continue to accept the elephant in the room: that one in three women in Europe and worldwide experience violence, and most never see the perpetrator held to account. An end to violence against women can be achieved if the necessary attention, long term commitment and resources are devoted to it. The sooner we start getting serious about it, talking about it and taking action, the quicker we will get to a world where women can participate and contribute equally, free from fear and safe from violence.

Karin Heisecke is a philanthropy professional and international expert on ending violence against women based in Germany. She is the Director of MaLisa Foundation and Senior Gender Advisor at the Amadeu Antonio Foundation.

The next issue of Alliance magazine, guest edited by Ise Bosch and Ndana Bofu-Tawamba, will dive deeper into questions around feminist philanthropy globally so make sure you are subscribed to get this issue in December.

Comments (0)