One of the lessons of the Millennium Development Goals was that collaboration across sectors will be essential if their successors, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), are to be achieved. There are already positive signs that philanthropy is rising to the challenge, prominent among them, the establishment of the SDG Philanthropy Platform and NetFWD as vehicles for philanthropic engagement with international development. How are Arab-region philanthropies faring on the SDGs?

To find out, we conducted a survey* earlier this year. Fifty-nine organizations from 10 countries (the majority, at 13 each, were from Egypt and Saudi Arabia) responded to the survey, 30 per cent of them foundations, 44 per cent non-profits, 9 per cent for-profit entities and the remainder a mixture of interested organizations including philanthropy infrastructure organizations.

In order to compare the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) picture with the rest of the world, our research builds on an existing global survey.

Prospects of engagement are good

While grantmakers from the Arab region are slightly less engaged with the SDGs than those from the rest of the world, there is still a demonstrable level of support for them, with the majority of Arab philanthropies actively gearing their activities towards achieving the SDGs.

Egypt Network for Integrated Development Initiative (ENID). SDG 8 is to ‘promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all’.

Over 90 per cent said they wanted to take part in the SDGs (interestingly, a higher rate than that of the global survey, which was 80 per cent) and almost a third (32 per cent) plan to play a ‘leading part’ in the SDGs. How far have these intentions been put into practice?

Just over a third (37 per cent) said that they had already engaged in discussions with government and other development actors, while a further 33 per cent have had internal discussions or are intending to do so (24 per cent).

The figures are similar to, although slightly behind, those seen globally. It’s only fair to note that a few expressed a marked lack of enthusiasm towards the SDGs. Anecdotal evidence suggests that is either because of a lack of clarity about the SDGs or scepticism about their value.

How well is the work of Arab philanthropy aligned with the SDGs?

Of the majority who did seem to be clear about the character and value of the SDGs, over half ‘strongly agreed’ that the goals are a ‘good fit with their work’.

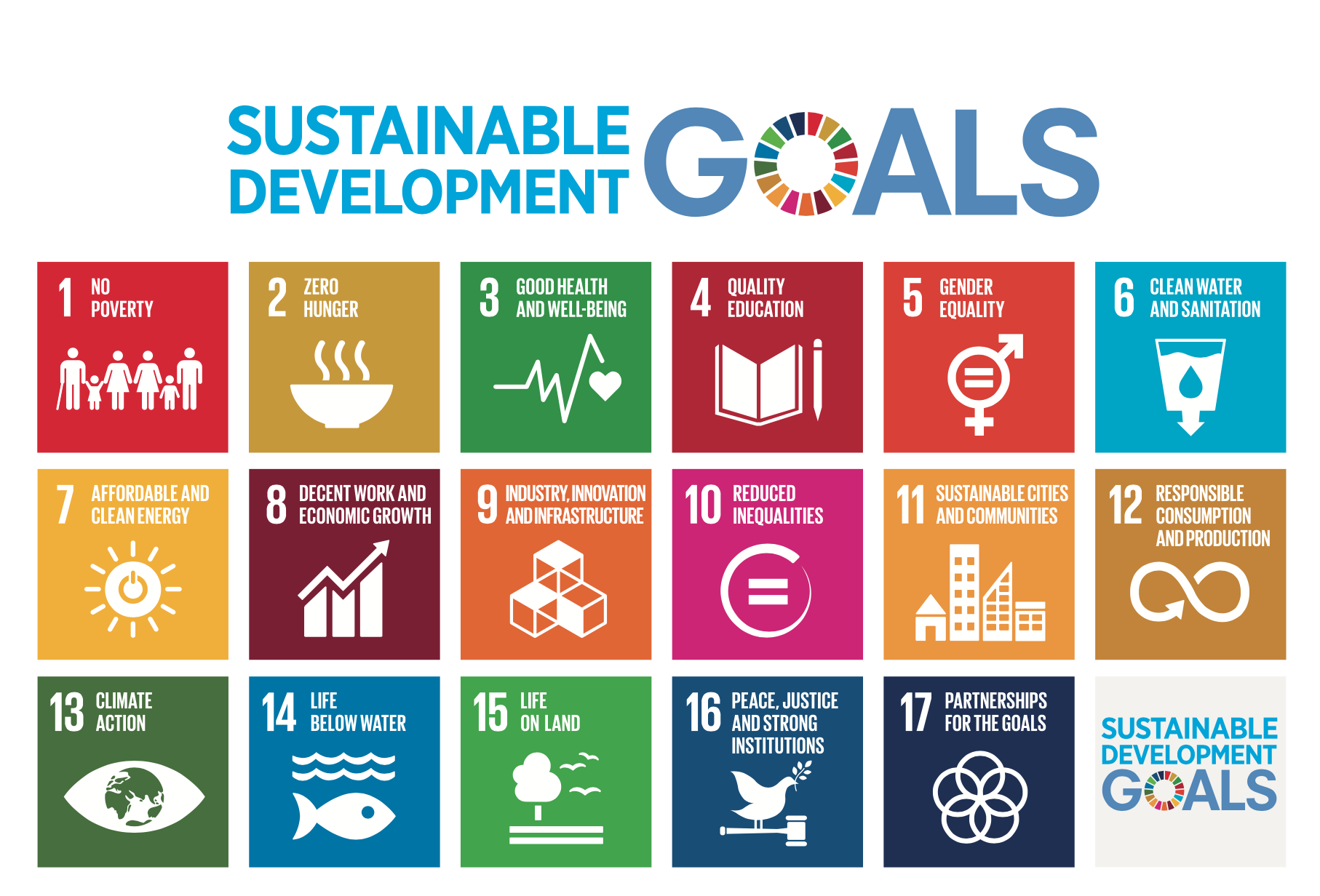

In terms of the alignment with the 17 individual goals, the best fit between what Arab philanthropic organizations do is with SDG 4 (‘ensure inclusive and equitable quality education for all’) followed by SDG 5 (‘achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls’).

Another good fit, in a region with high youth unemployment, is SDG 8 (‘promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all’). By contrast, those goals that are related to the environment and energy conservation were seen to be outside the sphere of work of Arab philanthropic institutions.

More surprisingly, there were considerable discrepancies between the Arab region and global results in other areas. On Goal 1, for example, to ‘end poverty in all forms everywhere’, most Arab respondents see no fit.

Again, global results show a good fit. Results on Goal 3 on health and Goal 17 on partnerships are also slightly lower than the global averages.

While no firm conclusions can be drawn on the basis of our limited sample, these results seem to indicate that Arab philanthropy is focused on the delivery of concrete services (jobs, education, healthcare) and regards poverty eradication or care for the environment as much larger issues that require government intervention.

At the least, this suggests that a more integrated philanthropic agenda in the Arab region incorporating environmental as well as social and economic considerations is needed, but it also implies the requirement for a greater appreciation of the virtues of partnership. All sectors will need to be involved in achieving the goals.

The relationship between philanthropy and government…

While the survey gave grounds for optimism that the SDGs might stimulate new forms of collaboration between philanthropy and government, it also uncovered some areas where trust and respect for each other’s mandates and approaches will need to be developed.

SDG 4 Education: Participants from the Gaza Strip in a workshop on communication at one of Bridge Palestine’s summer schools. Photo credit: Tafeeda Jarbawi.

Over half of the respondents strongly agreed that they needed to develop new relations with governments and 32 per cent agreed to a certain extent. This result is consistent with global results.

However, 15 per cent – a slightly higher percentage than shown in responses from the rest of the world – felt that government agencies were difficult to work with and indeed, many responses spoke of the need for ‘increasing communication with local governments’, ‘dialogue’, ‘building government capacities’ and ‘consultation and active engagement’.

More structural views expressed the need for ‘including SDGs in the national agenda and strategies’, ‘adopting a comprehensive rights-based approach’, ‘participatory planning approach’, and ‘evidence-based approach’.

A further area is regulation. Responses stressed the indispensable role of government in providing an enabling legislative and regulatory framework for philanthropy to contribute to sustainable development.

… and between philanthropy and civil society

The relationship with government is only one element of the collaborations that will be necessary to achieve the SDGs.

What of philanthropy’s traditional partner, civil society?

Over half of the respondents strongly agreed that they needed to develop new relations with governments. The split of the sample is roughly half and half between grantmakers who have a relationship with civil society organizations (CSOs) and work with them in all of their projects (54 per cent) and operating institutions (46 per cent) who implement their own programmes with only the occasional involvement of CSOs.

The fact the proportion of pure ‘funders’ is not higher may be the result of the lack of trust in the capacity of CSOs in some of the countries surveyed, though most responses favoured greater collaboration.

Responses stressed the indispensable role of government in providing an enabling legislative and regulatory framework for philanthropy to contribute to sustainable development.

At the same time, the responses showed a limited vision of partnership with civil society. Some were concerned about ‘overlap’, or achieving ‘complementarity’ and ‘splitting roles’, which overlooks the potential for synergy and partnership.

Many of the responses revealed a top-down view of the relationship between philanthropy and CSOs, suggesting that CSOs are simply a means of executing programmes or for local outreach.

Few responses perceived CSOs as ‘an integral part of the development model and approach to problem-solving’ and ‘the main actor in monitoring the implementation of the agenda 2030’.

Conventional and unconventional roles for philanthropy

The results of the survey show clear alignment between the SDGs and the conventional role of philanthropic organizations as flexible supporters of improved basic services, such as education. The survey also showed a willingness on the part of philanthropy to consider national priorities in alignment with their missions.

That is evident in the fact that 70 per cent saw it as their duty to understand the national goals set by ministries in countries in which they provide funding. However, an informed understanding of national goals is less well developed among the Arab region’s philanthropies than in other parts of the world surveyed.

Again, on a more operational level, while there was strong support for the idea of enabling CSOs to engage in the SDGs through convening, such support is lower among Arab philanthropies than among their global peers.

There was less enthusiasm for philanthropy as watchdog, monitoring the effectiveness of strategies to meet the SDGs, with fewer than 45 per cent strongly agreeing that they should take on the task.

This may be rooted in the conservative approach of Arab philanthropic organizations, especially towards public policy engagement.

For instance, there is less evidence of Arab philanthropy’s enthusiasm for support to civil society that monitors government or plays a whistle-blowing role.

The results of the survey show clear alignment between the SDGs and the conventional role of philanthropic organizations as flexible supporters of improved basic services, such as education.

Arab philanthropic organizations were also less supportive of the idea of using national and global statistics to decide what theme to focus on in a particular country. A possible reason is the scarcity of data in the region and limited awareness of the role it can play in identifying problems and possible solutions.

The gap between data and philanthropic planning and execution is another source of further investigation uncovered by the survey.

In conclusion

The results show willingness of Arab institutional philanthropy to embrace at least some of the SDGs. Operationally, efforts are already under way to integrate the goals in philanthropic organizations’ planning and action.

But two important questions remain: first, there remains a degree of mistrust between philanthropy and civil society and there is still room for improvement when it comes to establishing alliances and partnerships to ensure the fulfilment of the goals.

Second, Arab philanthropies will need to acknowledge more clearly the interrelationship between individual goals as a key element for their successful implementation.

As one survey respondent put it: ‘The SDGs are a powerful and inspiring framework’ that provide an opportunity for ‘those working on the same goals to collaborate and share strategies’.

For more discussion on the SDG debate, listen to our Alliance Audio podcast.

Atallah Kuttab is founder of SAANED for Philanthropy Advisory. Email akuttab@saaned.com.

Noha El-Mikawy is the Ford Foundation regional director for Middle East and North Africa. Email n.elmikawy@fordfoundation.org

Natasha M. Matic is chief strategy officer (CSO), King Khalid Foundation. Email natasha.m.matic@gmail.com

Barry Knight is director of Centris. Email barryknight@cranehouse.eu

Heba Abou Shneif is senior fellow, City University of New York. Email h.a.shnief@gmail.com

*The survey was undertaken by SAANED for Philanthropy Advisory, Ford Foundation Middle East & North Africa Office, and King Khalid Foundation with help from the Arab Foundations Forum (AFF) and the Gerhart Center for Philanthropy at the American University, Cairo.

| King Khalid Foundation |

|---|

| Saudi Arabia’s King Khalid Foundation (KKF) went through a thorough assessment of its goals and programmes in relation to SDGs, as well as the Kingdom’s Vision2030. This helped the foundation determine which SDGs are most relevant to its core competencies and how best to align its objectives with the national vision.

KKF accomplished this by undertaking both internal assessment with staff as well as third party assessment. The results contributed to a more focused strategy, better allocation of resources, enhanced local impact, and increased participation in the global progress towards sustainable development. However, SDG 17 still remains the most challenging in the face of a silo mentality prevalent among local organizations. KKF’s partnership with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is a successful example of a collaborative effort aimed at attracting young Saudi talent to work in the third sector. Ten fellows have been placed to work within non-profit organizations, while receiving continuous mentorship and training as they tackle the various challenges and opportunities of working in the development field. |

| Taawon |

|---|

| Taawon is an independent non-profit non-governmental organization (NGO) established in 1983 by a group of prominent Palestinian and Arab economic and intellectual figures, to support Palestinian communities in the West Bank, Gaza Strip, and refugees in Lebanon. Since its establishment, Taawon has invested around $700 million in programmes empowering Palestinians socially and economically to build resilience at the grassroots level and help provide for the basic needs of Palestinians.

Taawon’s interventions include investing in inclusive and equitable quality education (SDG 4) that improves economic prospects with decent employment (SDG8), encourages societal cohesion, sustainable communities and fosters national identity and cultural heritage (SDG11). For example, Taawon has invested in preserving historical centres and houses, allowing Palestinians to stay in their homes through its old city of Jerusalem revitalization programme (SDG 9). Its community development programme works to combat hunger (SDG 2), improve health and wellbeing (SDG 3), utilize renewable energy (SDG 7), and provide clean water (SDG 6). Its orphan support programmes are catering for around 4,000 children orphaned as a result of the conflict between Gaza and Israel. Taawon provides comprehensive support for the orphaned children and their families to reduce the inequalities (SDG 10) facing orphans in Gaza. The programmes are developed in partnership with Abraaj Group, Bank of Palestine and Qatar Development Fund respectively (SDG 17). Taawon’s 2016 sustainability report, prepared in line with global reporting standards, focused on level of compliance with the SDGs. For more information see http://www.taawon.org |

| Sawiris Foundation for Social Development |

|---|

| Sawiris Foundation for Social Development (SFSD) was established in 2001 as one of the first family foundations in Egypt. SFSD focuses on youth unemployment and addresses this challenge through training for employment, access to micro-credit and access to quality education. To date, SFSD has made a direct difference to the lives of 212,000 Egyptians in 23 governorates.

It continues to focus on SDGs 1 and 8 aiming to reduce poverty through economic empowerment and supporting the creation and placement of disadvantaged individuals in decent work. Additionally, the foundation’s programmes also focus on economic empowerment of women (SDG 5), particularly targeting female heads of households across rural Egypt. The foundation has been struck by the impact that female economic empowerment has on the entire family unit, in terms of better education and healthcare for the entire family. SDG 8 is also at the core of SFSD’s programmes through the provision of scholarships and supporting community schools. Its community schools programme now enables around 1,400 children to have access to quality education, and ensures that the teachers are continuously trained and children have access to proper nutrition in the schools. Finally, a key component of its work is partnering with other civil society organizations, the private sector and government (SDG 17). Partnerships with others has enabled the foundation to have stronger impact and reach and better coordination with other key entities. For more information see http://www.sawirisfoundation.org |

Comments (0)