The Hague, Netherlands

There are hundreds of thousands of charitable organizations across the planet, but private foundations are still a relatively rare breed.

While their forms vary according to context, what typically sets a private foundation apart from other charitable organizations is that they have their own sources of income. Those of us who work for or own a private foundation do not have to persuade governments, other institutions or the general public to fund our activities.

We have extraordinary levels of freedom to contribute to society in the ways in which we feel best fit with our own capacities. Whether charity or social transformation is pursued, we are afforded great freedom to use this ‘protected capital’ for society’s well-being.

But with that freedom comes a great deal of responsibility. Private philanthropy’s legitimacy rests on a social contract which includes a tax benefit in return for contributions to the public good. I believe that there are four ways in which foundations can embrace the promise to make their capital count.

Taking a longer view

The first and by far the most important is to tackle long term complex problems. Private foundations are unique in society in having resources and freedom to take the long view. Governmental parties are subject to periodic elections and shareholders are subject to market forces and tend to value maximum financial returns. Both operate in short term cycles that often lead to inadequate analysis and responses to complex social problems.

But foundations have neither elections nor shareholders. While social issues always come with a sense of urgency there is a need for foundations to approach intractable social problems from a long-term perspective.

Charities are well suited to address the urgency. Private foundations should lay the pathway toward permanent solutions.

Laying the groundwork for democracy is a long-term approach taken by the Ford Foundation over decades in South America and today by the Open Society Foundation and the Mo Ibrahim Foundation. Kellogg Foundation’s dedication to combatting racial discrimination is oriented towards long term social movement building. Long before Black Lives Matter, Kellogg was supporting African American communities in their struggle to be heard. Kellogg is an important force in planting the seeds of change that have grown into this social movement.

Backing ideas

The second is to fund ideas. Protected capital from private sources is exactly what societies need in times of scarcity to try new things. Governments cannot afford it and market forces can be punishing when new ideas fail.

Micro-finance, social entrepreneurship, impact investing and participatory budgeting are just a few of the ideas first supported by philanthropy that are now global in scope with strong social results. Foundations like Jacobs and Wellcome Trust continue to generate new ideas through financing research.

Taking risks

The third is to take risks. A foundation executive in the Netherlands who had recently come out of the private equity field once opined to me ‘why wouldn’t you risk this capital?

You have already agreed to give it away and you expect no returns!’ Returns are expected of course – predominantly social returns.

The sector can afford to risk its capital on new ideas, on research, on long term social problems and even to risk its reputation by supporting marginalized populations, dissidents, human rights or changes in the rules for the market place or even on democracy when our systems fail, as they are arguably now doing. Grappling with risk, however, has not been easy for the sector. Most still see it as something to avoid or ‘manage’ instead of embrace.

The broad view

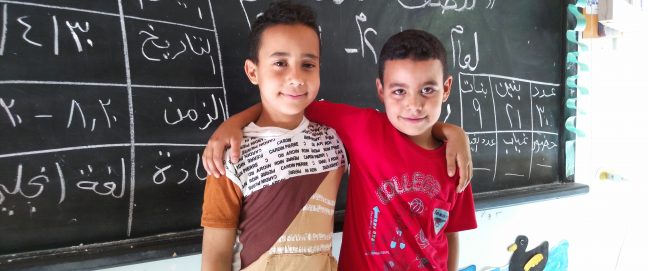

The fourth activity which solidifies the promise of philanthropy is to build fields, something which requires taking holistic approaches. Having a private income makes it easier to fund new ideas, to think long-term, to take a broader view, to take risks – drawing insights from different fields – and even to pioneer the creation of whole new fields. The field of early childhood development, for example, did not exist when the Bernard van Leer Foundation started funding projects for young children half a century ago.

It is no exaggeration to say that Van Leer played a role, along with others, in creating that field. The Peace and Security Funders Group which has a long-term approach that includes seven working groups each learning and sharing on a specific aspect of peace building is currently working to build that field.

On current trends: can philanthropy fulfill its promise?

How do current trends in philanthropy relate to the promise of a private foundation? Tackling long term problems seemingly flies in the face of some major trends in the field: the rise of spend down foundations, the fad for ‘big bets’ and the ongoing concern with impact measurement. In the first, many new philanthropists express a desire to see change in their lifetime on issues of their time. Many have come into resources at a very young age and are in a hurry to see results.

They do not necessarily equate solutions with building strong institutions – a signature approach of venerable philanthropies.

‘Spend down’ foundations too, however, have tackled long term complex problems and helped to build fields. A stand out is Atlantic Philanthropies which made its last grant in 2016.

Atlantic carried five portfolios in 8 countries for over 35 years addressing intractable problems, culminating in a series of big investments to take the work into the future. A spend down, or the ‘giving while living’ approach should not be confused with the pursuit of ‘quick wins’.

I have more concern about another trend in philanthropy: big bets’. A number of foundations have restructured their operations to devote big bet grants annually on a limited number of ‘solutions’.

While the desire to scale solutions is laudable, and some big bets like the Blue Meridian Partnership are promising long-term endeavors, I find the trend troubling. Big bets can fly in the face of tackling long term problems, building fields and testing new ideas.

For example, the 100&Change competition, announced in 2016 by the MacArthur Foundation included this statement: ‘By focusing on solutions we can inspire people to focus on problems that can be solved, and we just have to roll up our sleeves and get to it.’

This raises a number of questions for me. Where is the risk in funding known solutions to problems that can be solved? If the solution is known and not being taken up by other sectors (like governments or markets) an advocacy strategy or field building might seem a reasonable response, not $100 million to one organization to ‘fix’ the problem. We run the risk of ‘crowding out’ private sector competition and replacing public sector responsibility when we place a big bet.

The focus on known solutions can also crowd out the sector’s responsibility to address intractable problems where no known solutions are at hand like discrimination or human slavery. Who will search for the root cause?

Who will throw spaghetti at the wall until something sticks? If the solution is obvious we can reasonably ask why is it even on the philanthropic table?

Philanthropic dollars have always been critical to framing problems, testing new approaches, and supporting new ideas as many challenges do. The suggestion that we should only focus on problems for which solutions are known belies the underlying promise of a private foundation.

In search of impact

Tracking results through strategic philanthropy and impact measurement is gaining traction but also not without complications.

Critics of this approach equate evaluation and impact measurement with short term outputs, three-year program and project cycles and a rabbit hole of results, inhibiting the capability of addressing long term intractable problems.

I would challenge this critique. Compared to the approach proudly proclaimed last year by a philanthropist ‘I work intuitively’ having a strategy is far more likely to result in a kept promise to society. Impact frameworks can and should provide for short medium and long term measurements. First and foremost these are measurement tools rather than ends in themselves.

Two other trends are welcome but tricky: partnerships and mission-related investments. Partnerships between foundations promise greater impact and are very welcome. As we take up partnerships with other sectors, something also long overdue, the role of private philanthropy is to fund the less visible or high-risk components – embrace what is difficult for other sectors to undertake, not to replace or supplement governmental or market actors.

Similarly, as foundations align mission and assets, including through divesting and investing, being mindful of the difference between social and financial returns is critical.

There is a temporal mismatch on returns and the definition and tolerance for risk is not the same for social and financial returns.

Not all solutions lie in the marketplace and not all missions can be realized through market based mechanisms alone.

Foundations first and foremost are mission driven institutions. The trend to deploy capital across a spectrum from no returns to market based returns in order to achieve mission is welcome.

The temptation to compromise mission in order to receive greater financial returns, less so.

As the philanthropic sector grows, assessing our new approaches against the position we hold in society would allow us to keep faith with the underlying promise. Are we using this precious capital to tackle long term social problems? Are we advancing new ideas? Are we embracing risk and venturing where governments and markets cannot lead? Are we building fields that will benefit human kind over the long term? Let’s keep faith with the promise of a private foundation.

Alliance Philanthropy Thinker: Lisa Jordan

Lisa Jordan is a senior philanthropic executive with a twenty year career focused on social justice, impact and systemic change. She has served the largest foundations in the Netherlands, Porticus and the Bernard van Leer Foundation as top leadership and in the Ford Foundation as part of the management team.

Lisa Jordan is a senior philanthropic executive with a twenty year career focused on social justice, impact and systemic change. She has served the largest foundations in the Netherlands, Porticus and the Bernard van Leer Foundation as top leadership and in the Ford Foundation as part of the management team.

Visit The Philanthropy Thinker for more content from the series.

Comments (0)