When it comes to effecting positive change, what would be the impact if foundations had the same expectations for their endowments as they did for their grantmaking? As climate and health crises close in, more foundations are turning to social investment as another way to pursue their missions. In the UK, new research has found that more than three-quarters of charitable foundations have a policy to invest their assets in line with their mission. And globally, almost 90 per cent of foundations have indicated they’re interested in social investment, according to research by Foundation Source.

It’s time to ask: what is the emerging best practice when it comes to impact investing, and how is this reflected in how foundations are investing around the world?

At the beginning of 2020, before the world was rocked by Covid-19, Cazenove Capital asked charity investors in the UK how they were investing their assets in a way that aligned with their mission and aims. Over the next decade we will have to face the ramifications of the global pandemic, whilst also tackling rising inequality and the urgent need for action on climate change. It is no wonder, then, that many foundations are asking themselves what their role is in creating this change and how they can use all of the assets at their disposal to push for progress.

The rising tide of responsible investing

In the investment world, we are seeing this this ambition through the continued rise in adoption of responsible investment policies. Foundations increasingly want to use their assets to have impact, not just to fund spending. Our research found that 77 per cent of charity investors in the UK now have a policy to link their mission and aims to their investment portfolios; increasing from 59 per cent five years ago and 23 per cent a decade ago. This increase in adoption has also coincided with a fall in the perception that responsible investment practices reduce returns. Sixty-one per cent of charity investors now believe that these policies make no difference to returns, with 27 per cent believing responsible investment practices increase returns. It is hardly surprising then, that most charities now expect their investment managers to integrate environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors into investment decisions – which was the most cited reason for adopting a policy.

The regulators have also taken a more supportive stance, with the Charity Commission for England and Wales describing their own guidance as ‘permissive’ and welcoming ‘signals that charities are thinking about how to reconcile achieving good returns with responsible investments that align with the charity’s mission and purposes’.

This is in contrast to the recent rule proposed by the Department of Labor in the US that prevents fiduciaries of employee benefit plans from pursuing ‘non-financial objectives’, like environmental, social and governance (‘ESG’) objectives, if doing so puts returns or participants at risk. Although this doesn’t limit foundations and endowments, perhaps it is useful context to understand the lower level of uptake of responsible investment practices by other US institutional investors like endowments. The NACUBO-Commonfund study of US college and university endowments in 2017, found just 24 per cent were using ‘responsible investing’ or ‘ESG’ strategies. Of course there are some notable exceptions to this trend. Trailblazers like the Heron Foundation who in 1996 experienced a ‘tipping point’ when their board moved from viewing the endowment solely as a source of spending, to seeing it as an asset base capable of generating greater social impact. Now, they invest 100 per cent of their assets for impact, whilst noting the challenges in finding investment opportunities that exactly align with their mission.

There are encouraging signs that barriers to investing more assets for impact are falling away. Our research suggest a significant drop in fears that a more impact focused would hinder returns from 33 per cent to 17 per cent of survey respondents. Credit: Cazenove Capital

There are encouraging signs that barriers to investing more assets for impact are falling away. Our research suggest a significant drop in fears that a more impact focused would hinder returns from 33 per cent to 17 per cent of survey respondents.

That said, our research suggest barriers remain including a lack of clarity around fiduciary duty in Charity Commission guidance, a lack of robust impact investing opportunities and cultural inertia and conservatism among trustees.

Climate change is a defining theme

But arguably it is in the area of climate change where we are seeing the most profound shift In the UK there is a dramatic increase in the inclusion of climate change as part of investment policies. Twenty-six per cent of responsible investment policies now include a specific statement on climate change, with fossil fuel exclusions increasing from four per cent of exclusions to 33 per cent in the last five years. The divestment movement has been particularly strong in Universities across the globe, with students taking to the streets and sometimes even camping out in finance departments to have their voices heard.

Many Foundations are electing to divest from all fossil fuels, but we are also seeing examples of more nuanced approaches – with investors such as the Church of England adopting a climate change policy that favours engagement to encourage alignment with the Paris Agreement, combined with divestment from those companies failing to meet transition targets, that increase as action becomes more urgent.

‘Failure to make a significant move away from fossil fuels will tie the world into escalating physical damage, rising sea levels, less agricultural land and more volatile weather. In the 1960s, emissions were half of what they are today. Returning to that relative level by 2030 … will require capital reallocation on a huge scale and drive disruption across every industry.’

The focus on climate is hardly surprising. Andy Howard, Schroders’ Global Head of Sustainability says that climate change will reshape the environment and the global economy over the coming years. ‘The International Panel on Climate Change has warned that we have a decade to roughly halve global greenhouse gas emissions. Failure to make a significant move away from fossil fuels will tie the world into escalating physical damage, rising sea levels, less agricultural land and more volatile weather. In the 1960s, emissions were half of what they are today. Returning to that relative level by 2030 – when the world’s population will be more than twice as large and its economic output roughly ten times bigger – will require capital reallocation on a huge scale and drive disruption across every industry.’

This suggests an imperative for long term investors such as foundations to consider climate change as part of their investment decisions; reducing risk by allocating away from investments contributing to the problem, and benefitting by actively investing in solutions, like renewable energy or sustainable infrastructure.

Credit: Cazenove Capital

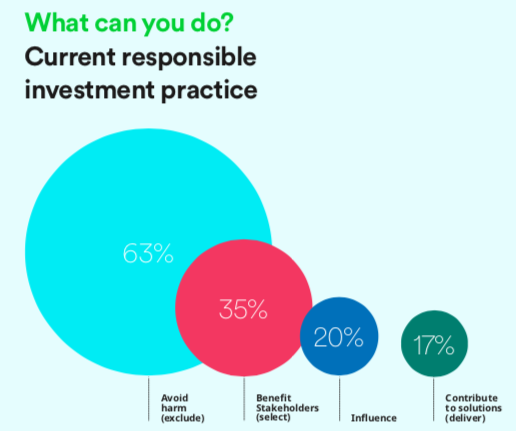

Moving from avoiding harm to having a positive impact

Many foundations still start from a position of seeking to avoid harm, with exclusionary policies the most common way to apply responsible investment principles – either by restricting investments that directly conflict with the mission, or removing those perceived to have a detrimental impact on wider society. In the UK, the top five exclusions from charity portfolios have remained consistent over the last five years, with tobacco, armaments, pornography, gambling and alcohol all commonly avoided. These are often grouped together and referred to as the ‘sin stocks’ referencing their frequent exclusion from religious portfolios.

However, best practice has evolved, with a number of foundations moving beyond avoiding harm to measuring and managing the impact of their investments. In practice this includes both how they invest and how they use their influence to push for change. In Asia, the family office RS Group is adopting a ‘new collaborative approach to investment, business and philanthropy’. Their approach is based on creating ‘blended value’, both financial returns and environmental and social value, across their total portfolio of assets. On the other side of the world, the KL Felicitas Foundation, a family foundation in California, also seeks to balance social and financial return for 100 per cent of their endowment and has worked with NPC to publish a useful summary of their findings. Here in the UK, purpose-led investors like the Friends Provident Foundation, Joffe Trust and the Blagrave Trust are collaborating to showcase best practice, and to use their influence to catalyse change in the investment industry. It is clear that this broader, more intentional approach to understanding the impact of investments is the new frontier of responsible investing for foundations.

Kate Rogers is the Co-Head of Charities at Cazenove Capital.

The views and opinions contained in this article reflect the opinions of the author.

Comments (0)