When it comes to ethical choices, you can’t hide behind neutrality. GlobalGiving has been exploring a new way of dealing with ethical dilemmas that is not based on black-and-white judgments.

Alix Guerrier, CEO of GlobalGiving, invites platform stakeholders to vote on whether the concept of neutrality ‘can work’ or ‘is garbage’.

GlobalGiving connects non-profits, donors and companies around the world, primarily through its online crowdfunding marketplace, GlobalGiving.org. It began in the early age of the internet when optimists believed that broader access to a marketplace of ideas would allow the best ideas to rise to the top, but any casual user of the internet can attest that that is not what’s taken place.

Hate speech, interest groups and polarisation have thrived online, and platform providers are constantly facing scrutiny over the content of their websites. This applies to many online philanthropic platforms, too, and to some extent, the many players in the philanthropic space who play intermediary roles. Over the past two decades, their neutral stance has been called in question by people with conflicting values. Platforms like GlobalGiving face frequent dilemmas about who’s on, who’s off, and who gets promoted in our marketplace. Decisions by our staff carry tremendous weight for the non-profits and communities we seek to serve.

This is the problem we’ve called the ‘Neutrality Paradox’: despite attempts to be open, inclusive, and neutral, in the end, as we and our peers including Charity Navigator, Candid (formerly GuideStar and Foundation Center), and BetterPlace.org have recognised, we must often make moral judgments when facing a dilemma.

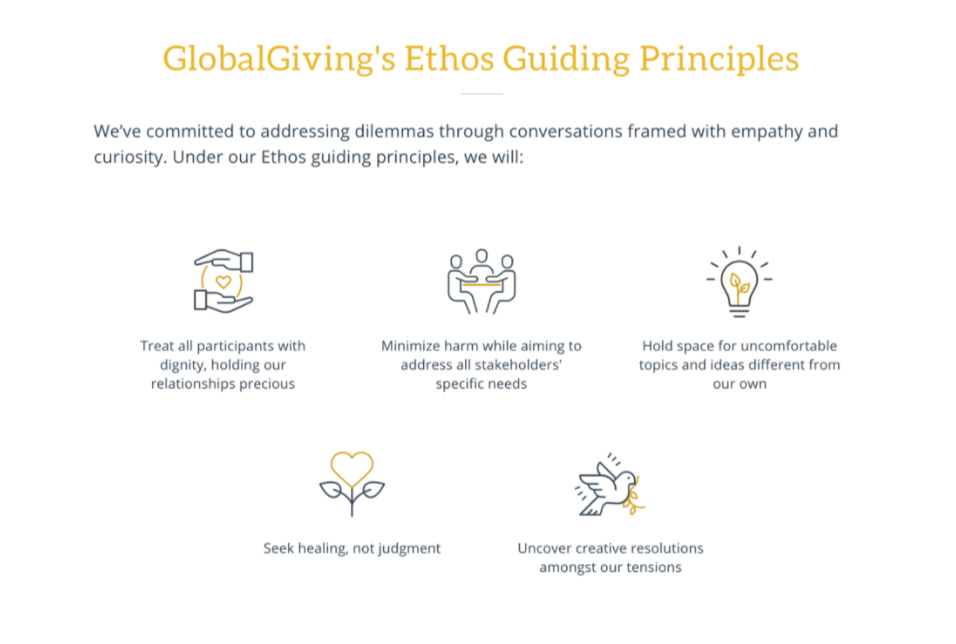

Ethos is a human-centered approach to difficult conversations. It acknowledges and honours different values, but asks everyone to step into a deeper agreement about how we’ll act, rather than why.

Curation dilemmas threaten platform integrity

In late 2018, I received an email from a journalist at the UK newspaper, The Guardian, who had recently published an exposé about an Indian non-profit supported on our website. It described itself as working for the welfare of women and children who are victims of commercial sexual exploitation. The journalist alleged the group was violating international human rights standards in the way it detained sex workers, some of whom engaged in sex work by choice. Our investigation team visited the organisation and conducted many external interviews as part of our due diligence, but we lacked a framework for making a decision about whether this organisation, which was abiding by (and enforcing) national Indian laws, should be allowed to continue to fundraise on our global platform.

This dilemma, like many others faced by every platform today, poses moral questions to staff and leaders and threatens the integrity of our charity and business models. As one platform leader said at an event in London, ‘no matter how personally passionate we are about an issue, it always comes down to an assessment of risk’. In the end, folks make decisions under the great cloud of potential reputational risks to ourselves, our partners, and the entire ecosystem of platforms.

‘There’s no such thing as neutrality’

Tarleton Gillespie, author of Custodians of the Internet, made this point at a Neutrality Paradox roundtable in late 2019. ‘Big platforms love saying they are neutral/hands-off. But that is garbage. Platforms remove content all the time (like porn and spam) and that’s relatively uncontroversial. But those are value judgments. Every platform is making value judgments.’

Openness is not a passive stance. It is an explicit rejection of exclusivity and discrimination. The Ethos approach is an invitation to host what we’re calling ‘inclusive conversations’ in the face of tension.

The concept of neutrality does not adequately reflect the values that ground our mission, culture or community as a social purpose organisation. Any platform that chooses to connect individuals with ideas implicitly takes a degree of responsibility for those ideas and any technology is underpinned by its creators’ values.

So, if the leaders of a platform are responsible for the ideas on their platform, and they can hide behind neither an assertion of ‘neutrality’ nor a system of mechanistic rules and criteria (or even, in some cases, other platforms that are doing their thinking for them), what should happen next? This is the dilemma.

GlobalGiving’s Ethos solution

GlobalGiving recognised there had to be a better way to moderate and curate our marketplace. We did some research among peers and stakeholders, which included 19 interviews with people from 16 organisations, including our own, to collect 41 examples of dilemmas. We found most dilemma decisions (80 per cent) were not governed by explicit, pre-existing policies. Furthermore, a majority (61 per cent) of decision-makers did not feel prepared to address the dilemmas they described in the interviews.

This year of research and prototype testing led us to a resolution of the Neutrality Paradox, what we’re calling GlobalGiving’s Ethos, the first step of whose process is for leaders to ground themselves in their values. One of GlobalGiving’s core values is ‘Always Open’, which is based on the belief that ‘good ideas can come from anyone, anywhere, at any time’. GlobalGiving decided to double-down on this commitment to openness and inclusion. Openness is not a passive stance. It is an explicit rejection of exclusivity and discrimination. The Ethos approach is an invitation to host what we’re calling ‘inclusive conversations’ in the face of tension.

This year of research and prototype testing led us to a resolution of the Neutrality Paradox, what we’re calling GlobalGiving’s Ethos, the first step of whose process is for leaders to ground themselves in their values. One of GlobalGiving’s core values is ‘Always Open’, which is based on the belief that ‘good ideas can come from anyone, anywhere, at any time’. GlobalGiving decided to double-down on this commitment to openness and inclusion. Openness is not a passive stance. It is an explicit rejection of exclusivity and discrimination. The Ethos approach is an invitation to host what we’re calling ‘inclusive conversations’ in the face of tension.

But the next important step in this process is to recognise that not every stakeholder or user will share the same values so platforms should establish some guiding principles and shared behaviours, which become their working Ethos. You can think of the Ethos as agreeing on a way to behave – the ‘how’ – even if we don’t agree on the ‘why’.

When we encounter a dilemma, our teams are prepared to ask open-ended questions and elicit deeper understanding of the values and perspectives involved, long before coming to decisions that move us into action and resolution. This type of conversation leads to resolutions that go beyond the binary yes/no, on/off decisions that usually come with moderation.

An example of this is a case which involved a non-profit partner that had been accused by others of being affiliated with a terrorist organisation (allegations which were difficult for us to investigate). If we continued to allow this group to fundraise, we would lose one of our valuable payment partners who’d decided they would cut ties with anyone supporting the accused organisation.

In the end, folks make decisions under the great cloud of potential reputational risks to ourselves, our partners, and the entire ecosystem of platforms.

‘We’d considered our options binary: either keep them on the platform as a partner, or remove them. It was through Ethos – and the encouragement to really think about what our partner’s core needs were – that we came up with a potential “third path” that might satisfy their primary need while still protecting GG’s business needs,’ said Michael Gale, GlobalGiving’s programme director. By exploring the user needs – the ‘jobs to be done’ – of all the stakeholders, we came to understand that the accused organisation might be partially satisfied with a letter from GlobalGiving confirming it met our vetting standards, even if it wasn’t included on the platform. This letter made it possible for us to begin to seek healing in a relationship that had been otherwise broken.

Ethos conversations might be held by our management team, another internal team, or an ‘Ethos Council’ made up of our stakeholders. We’ve created facilitation and discussion guidelines and are working to build internal capabilities to engage in difficult conversations with empathy and curiosity. We’re also committed to publishing our processes and decisions more transparently, to better serve all our stakeholders. This includes clear and accessible terms of service, a simple process for users to submit concerns, an explicit protocol for leaders to address dilemmas; clarity about where ultimate accountability lies, and the means for users to address grievances, obtain remedies, and publicly share their perspective. There will also be a means for our team to revisit a decision, acknowledging this is a learning process for all. Clearer documentation of decisions and recommendations is part of the Ethos process, in order to build institutional knowledge and trust around our work.

A human-centered approach

When I first set out to help GlobalGiving respond to the case in India, I believed we just needed to get clearer on our stance for all the hot-button issues. What do we believe about vaccinations and alternative medicines, for example? What’s our stance on whether LGBTQ groups should be allowed to fundraise in countries where their orientation is illegal, and therefore the group can’t meet our official registration requirements? Having seen the research on orphanages, should we cut all orphanages from the GlobalGiving site? It’s tempting when faced with these questions to seek out clear lines in the sand.

We tried to come up with a matrix that would set out all the considerations and lead us to the right choice. But the nature of a dilemma is that there is no easy or even ‘right’ choice and there definitely isn’t an algorithm we can programme to deliver an answer that feels good to everyone. So we scrapped the matrix, and instead, we’re offering a framework for hosting inclusive conversations with empathy and courage.

Ethos is a human-centered approach to difficult conversations. It acknowledges and honours different values, but asks everyone to step into a deeper agreement about how we’ll act, rather than why. We’ve now tested this approach with 10 different internal and external groups, and we feel confident that the Ethos approach can provide a way to build and uphold our integrity. When the next dilemma comes along (as we know it will) I can’t guarantee we’ll come to the perfect resolution, but I can promise we’ll have addressed it with curiosity, empathy and with a clear process for finding creative resolution to the tension.

Alison Carlman is director of Evidence and Learning at GlobalGiving.

Email: acarlman@globalgiving.org

Twitter: @acarlman

Comments (0)