Talk of the ‘post-aid world’ is everywhere. Sweden, Finland, Germany and the Netherlands have joined the UK in huge cuts to official development assistance. This is resulting in large-scale redundancies for INGOs that have pursued aggressive growth strategies, such as Save the Children and the International Rescue Committee. Such redundancies are likely to increase as the EU, which the largest global provider of ODA, reviews its position. Moreover, November’s US Presidential elections may have a major effect on USAID.

While painful for many people and organisations, this is an opportunity for reform. ODI has pointed out:

‘We are getting closer to a tipping point where demands for systemic transformation are becoming too loud to ignore. Everyone seems to be talking about how the North-South model of aid is obsolete. At this moment of reckoning, ODI is asking what a post-aid world should look like and what role would donors play within it?’

The United Nation agrees that the system is broken. At last year’s General Assembly, António Guterres, Secretary General, said:

‘… global governance is stuck in time. Look no further than the United Nations Security Council and the Bretton Woods system. They reflect the political and economic realities of 1945, when many countries in this Assembly Hall were still under colonial domination.

The world has changed. Our institutions have not. We cannot effectively address problems as they are if institutions do not reflect the world as it is. Instead of solving problems, they risk becoming part of the problem.’

The problem is widespread failure – not least in Gaza, Sudan and Ukraine. Much of this is due to the ‘humanitarian oligopoly’ of INGOs. As the main instrument of the aid system, they crowd out national and local actors that are better placed to respond to crises. As Joshua Craze points out in The Angel’s Dilemma, ‘humanitarian spending doesn’t follow a moral geography of need but a political cartography determined by donors.’ The consequences are starvation for local organisations, the bedrock of civil society. In Ukraine, for example, only 0.07 percent of total funding has directly gone to Ukrainian organisations.

Deborah Doan’s new book The INGO Problem summarises the evidence behind INGO failure[1]. Supporters of her thesis include Amitabh Behar, Executive Director of Oxfam International, who said in a 2022 interview that INGOs had:

‘…compromised on upholding the normative moral compass by going after scale and size; by replicating the existing power structures of the unequal and unfair economic and political order; by developing hollow rhetoric around deeply political questions of race, decolonisation and neo-liberal capitalism; on ensuring delivery to the last mile and instead have developed their own flab.’

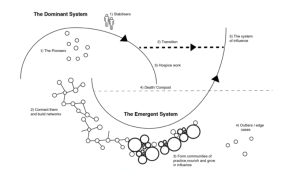

As the old system crumbles, there is the opportunity to replace it with one that puts people in communities first. This is the essence of the #ShiftThePower movement’s approach. By focusing on the interaction between dominant and emergent forces in systems (see the diagram) we start to see alternatives emerge as the system begins to collapse and give way to the new. This frame helps us to see where we need to work, so we emerge as a ‘system of influence’.

As the old system crumbles, there is the opportunity to replace it with one that puts people in communities first. This is the essence of the #ShiftThePower movement’s approach. By focusing on the interaction between dominant and emergent forces in systems (see the diagram) we start to see alternatives emerge as the system begins to collapse and give way to the new. This frame helps us to see where we need to work, so we emerge as a ‘system of influence’.

At the same time, there is no guarantee that the new system will favour people in civil society – still less be based on the principle of ‘flourishing lives for all’. Indeed, the dominant strands in reform among bilateral donors are to increasingly respond to right-wing populist demands to support domestic needs, migration control and business growth. The Dutch Government’s September budget which announced €330m cut for development aid in 2025 was clear that remaining funds also needed ‘to support Dutch companies that do business internationally’. Alongside this, efforts to hit ‘localisation targets’ remain elusive.

This is unfortunate because the essential message emerging from the #ShiftThePower movement is that when communities are in charge of their own destinies another way is possible. The Bogotá summit inspired hope and joy, and a survey of participants suggested that a good society depends on shifting the power balances in three main ways:

- Trust – Governments, funders and public organisations become enablers, trusting people and communities to take the lead to build the societies they want

- People power – Community activism is nurtured, supported, and resourced so all people take charge in building the societies they want – generating empowerment, ownership and agency

- Feminisation – The world embraces feminist values, and universal dignity and wellbeing for all people is the superordinate goal over economic growth

These three ideas, when combined, have the power to transform our world. The ideas may be simple, but they have emerged from hierarchical multiple regression modelling. This has absorbed the complexity of views and distilled the findings into what really matters. This gives them a legitimacy in guiding positive change.

If we treat these three ideas as ‘good enough for now’ we can avoid the ‘tyranny of perfection’ in which progressive actors obsess about the meaning of particular words. We can use the values and principles to guide action regardless of the particular field an organisation is working in – whether it is environment, human rights, peacebuilding, gender, or humanitarian relief.

To organise around the new narrative, we need safe spaces to develop actions based on it. This needs to be a weaving process which downplays individual egos, organisational logos, sectoral silos, and moral halos, while building a common agenda. Chandrika Sahai in Facing the Inner Crisis in Philanthropy identifies three factors to help support this: humility, connection, and care. Such conversations would provide space to connect with our collective wisdom of driving and sustaining change. Elizaphan Ogechi provides further helpful guidance in The Seven Lost Secrets of Social Movement Building.

The objective of the weaving would be to build both the ends and the means of systems change by fulfilling an observation made by Nobel Prize winning chemist, Iiya Prigogine:

‘When a complex system is far from equilibrium, small islands of coherence in a sea of chaos have the capacity to shift the entire system to a higher order.’

To support this process, we need philanthropies committed to systems change to step into their role as trusting enablers. This is so much more than participatory grant making or trust based philanthropy, where, as Nina Blackwell has pointed out, definitions of ‘trust-worthy’ are often ‘built on paradigms and standards that are Global North dominant, Western-normative, and often overly capitalistic.’ It is about becoming a servant to the process that connects the ‘small islands of coherence’. This involves funders acknowledging that the current system is broken and more money into a broken system is not the answer.

If it takes a village to raise a child, it will take the ecosystem to change the system. This work can only begin when we start to unite around the story of the system we want, rather than what we don’t want.

Rebecca Hanshaw is an independent consultant and philanthropy advisor.

Barry Knight is Secretary to Centris trustees.

Comments (0)