Jeff Bradach, co-founder of the Bridgespan group

Jeff Bradach is co-founder of The Bridgespan Group, arguably among the world’s most influential non-profit and philanthropic advisory firms. Best known today for advising leading philanthropists, including Mackenzie Scott, on donating billions of philanthropic dollars, Bridgespan itself is branching out with over 300 members of staff and offices in South Africa and India as well as across the US. Bradach tells Charles Keidan that ending racial disparities is the route to social justice in the US and beyond.

Rising to the challenge

Charles Keidan: What are the most significant changes you have seen since you founded Bridgespan in 2000?

Jeff Bradach: For one thing, a significant uptick in collaborative structures – such as Blue Meridian, ClimateWorks, Co-Impact, New Schools Venture Fund, Dasra, Democracy Frontlines Fund, GROW fund and so many more.

There is also money flowing through different philanthropic structures, not just foundations, for example, limited liability companies (LLCs), donor advised funds (DAFs), crowdfunding, corporations with the corporate social responsibility (CSR) law in India. And if we broaden the frame beyond philanthropy to capital for impact we see tremendous growth in how for-profits are adding social impact more intentionally into what they do via impact investing and environmental, social and governance (ESG) investing, for example. The rhetoric about impact is far outpacing what is actually happening but the flows of money are enormous and the interest in many cases is authentic. It will translate into significant impact in the world.

Calculations suggest there are 5 times more billionaires today than there were 25 years ago when Alliance was born. Is this growth of billionaires an opportunity for philanthropy or a problem for society?

I think it’s both. It’s an opportunity for philanthropy as shown by people signing on to the Giving Pledge, broader commitments to giving and so on. But it is born of a dramatic uptick in inequality and that is a problem for society. That’s something that needs to be worked on and philanthropy has a role in addressing.

Some suggest that, in addition to their philanthropic giving, more philanthropists could back calls for a wealth tax to help reduce economic inequality. What do you think about that suggestion?

We are not experts on tax policy and it’s hard to say without understanding what the policy would look like. But the trajectory we are on of greater and greater wealth inequality is not healthy for a just, equitable society where all flourish. Taxes are certainly part of creating greater equity, and so is the role of government in stimulating private action for public good.

One particular aspect of inequality is racial inequality. This has come to prominence through the Black Lives Matter campaign and it’s an area that Bridgespan has been particularly active in. Where do you see philanthropy playing a constructive role in this issue?

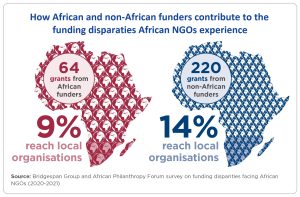

Bridgespan’s mission is focused on addressing issues of inequity and core civil and human rights and when you look at issues in health, education, or jobs – virtually every area – race is one of the biggest predictors of outcomes. We were slow to see how central it is but now, when we take on a consulting engagement, we always raise the question of how race and other dimensions of equity are involved. We’ve done reports on racial barriers to philanthropic capital in the US and we just did a report with the African Philanthropy Forum on inequities in funding flows to African NGOs. We’ve come to the very clear conclusion that structural racism in the US is a core issue in any consideration of justice and it needs to be addressed directly.

In terms of this work, it’s worth underscoring that we see ourselves as collaborating with other organisations on these issues of equity and justice – the partnership with the African Philanthropy Forum, with Policy Link, with Echoing Green, with the Association for Black Foundation Executives (ABFE). We have no illusions that we were the first to work on racial barriers to capital or that we fully grasp the issues involved. ABFE has been working on these issues for over 50 years. We have the privilege of working with organisations and individuals who have been the leaders in this field. Our role in many ways has been to elevate their voices.

There has been some tension within the American philanthropy community about racial justice. How do you navigate such increased polarisation?

US philanthropy has always spanned very diverse perspectives and there are spikes of reaction to those perspectives. Bridgespan is unambiguous about it: we don’t think there is a way to make progress without recognising the structural dimensions of racial injustice in the United States. For example, if you look at any of the celebrated success stories in social change in the US – reduction of teen pregnancy, smoking cessation, the spread of the hospice movement as a form of palliative care – you would find that it was a success story particularly for white people. But if you disaggregate the data, they were much less so for people of colour. And if you look at things like the racial wealth gap, you simply cannot understand the problem or design solutions without taking race into account. That’s true on almost every issue we work on.

Within philanthropy itself, some of the leading foundations aren’t diverse at all. Do you think they should be required to diversify their boards to bring in the experience of the people they’re aiming to serve or do you think that should be their decision?

We believe strongly in the importance of diversity on boards and staffs of philanthropies. That said, it isn’t clear what the impact would be of mandating such a change, so we would want to dig into that. I think change is more likely to occur through collective peer and public influence, which we are seeing in some places.

There are currently discussions about the ACE Act and calls in the US for increasing both foundation payouts (currently at 5 per cent) and introducing payouts from donor advised funds. What is your position on that?

A big part of the magic of philanthropy is the independence it has to pursue whatever charitable purpose the donor desires. At the same time, our tax system grants tax breaks to donors because of the expectation that the charitable contribution will flow to action in the world, so it’s fair to ask whether that expectation is being fulfilled if money sits in DAFs for long periods of time. It’s a balance – providing donors with flexibility and independence while at the same time holding them accountable for putting the money to work in communities. I think it is good that this issue is now being examined.

There’s a greater degree of transparency about foundation grants, but less so when funding comes from DAFs or LLCs. How important is it for all funders to be transparent about the decisions they make?

Transparency is very important. Structures like DAFs and LLCs pose new questions about that. As many observers have pointed out, philanthropists possess a lot of power to influence our collective lives – both directly and via influencing government and business – and it should be subject to some expectation of transparency. Again, it’s that balancing act between autonomy and accountability and where you draw the line. The devil is in the detail.

In recent years, Bridgespan has opened offices in India and in South Africa. It’s been suggested that there’s a shift in philanthropic power from the Global North to South. Do you think that is overstated or actually something that is beginning to occur?

A bit of both. There is real action but the rhetoric is ahead of it and there’s a tremendous distance to travel. That recent report we did with the Africa Philanthropy Forum was eye-opening. There were 64 gifts of over $1 million from African funders between 2010-2019 but only 9 per cent of these gifts are funding local African NGOs. Of large gifts from outside sources, only 14 per cent is going to African NGOs.

The trajectory we are on of greater and greater wealth inequality is not healthy for a just, equitable society where all flourish

The discussion about proximity and about local solutions is a core paradigm shift that we’re in the middle of. You see the same pattern in discussions about trust-based philanthropy, how you accompany local actors in their work, rather than exercising control over them. That shift needs to happen if we are to really address problems of equity and break cycles of poverty and injustice.

What prompted Bridgespan to open offices in the Global South?

We were aware that there’s a tremendous amount to learn from the Global South. If you’re an adviser, you can’t claim that you’re looking at the most powerful examples of any practice or organisation if you’re only looking at your own context. That’s been borne out in the first five or six years of our work globally. If you look at our articles, you’ll see examples for Rwanda on peer-driven change, or the extraordinary scale stories of Indian NGOs. The Global North has much to learn from the Global South. In addition, in our experience of working in South Africa and India, the amount of cross-pollination between India and Africa is huge. That’s invisible if you’re sitting in New York. The second part is that wealth is growing much more outside North America than inside, accompanied by interest in philanthropy and civil society.

Most of current spending on philanthropy infrastructure – an estimated 80 per cent – is concentrated in the US. If philanthropy in the Global South is to grow, does it need to pay more attention to building the infrastructure that can support it?

The lack of it means that non-profits have to rely on local invention to solve problems which have already been solved elsewhere. That’s a burden on both them and the philanthropists which intermediary organisations could help with. Bodies like WINGS, like the African Philanthropy Forum and media publications like the India Development Review and Alliance are huge multipliers to the kind of impact which philanthropy and non-profits can have. I would say they’re all under-invested in and philanthropy would really be wise to see these as collective goods.

What do you think is the value of specialist sector media and how independent should it be of the field that it serves?

Specialised sector media is particularly important as it offers a depth of knowledge from which people can learn. It is also a crucial element in holding the field and its players accountable.

I remember 20 years ago when people asked ‘What should I read about philanthropy?’ there was almost nothing. There has been a tremendous shift in the ecosystem since – research programmes in universities, publications like Alliance, Stanford Social Innovation Review, Nonprofit Quarterly, IDR, and a host of books, advisory organisations like Arabella, FSG, Dalberg, GiveWell, Bridgespan, RPA, and data and trust-building entities like Candid and the Global Impact Investing Network. There is still much more to do – especially in the Global South – but even there you see the emergence of organisations like AVPN, African Philanthropy Forum, Give India and many others.

How do you see philanthropy practice changing?

Probably the biggest one is the centring of leaders from the Global South and leaders of colour in the formulation of what needs to be done. This is not a new idea, but it has certainly gained attention in the wake of Covid, the George Floyd murder and broader discussions about decolonising aid and philanthropy. It’s still an open question of how broad and deep the change will be but real shifts are happening.

It’s that balancing act between autonomy and accountability and where you draw the line. The devil is in the detail.

Similarly, interest in trust-based philanthropy can be seen in lots of places – the pledge by 800 funders in the US to release restrictions on grants, the recent announcement of the GROW Fund in India and the Black Frontlines Fund in the US to support grassroots leaders with unrestricted grants, etc. Some of this was accelerated by the Covid crisis, but it is also responsive to the larger idea of people close to the ground being the source of solutions and agents of their own destiny.

It’s worth noting that trust-based grantmaking is often juxtaposed with ‘strategic grantmaking’ but I think the latter is also an important shift over the past 20 years. The reliance on data, analysis, evaluation, evidence has helped to advance our understanding of what works and what doesn’t. The shift has added very important dimensions to how social change leaders and philanthropists engage in their work and has centred discussions about impact in important ways.

What do you think philanthropy should prioritise in the coming years?

There are core structural inequities which unfairly disadvantage, for example, people of colour and women. When I think of the role of philanthropy, an important element is to contribute to a world where those demographic characteristics aren’t predictive of outcomes. You can boil it down to that. We’re a long way off but we see more clearly where some of those challenges are and hopefully can work on those more directly over the next decade. There’s also a role for philanthropy in the giant existential issues like climate change.

Transformative Impact Summit 2017 co-hosted by Bridgespan and Harvard Business School’s Social Enterprise Initiative.

I think we are entering a period of great ferment in philanthropy. Let me name three things I hope to see:

First, a dramatic increase in the amount of philanthropy – and the proportion of it going to the work of social service and social change. Big institutions like universities and hospitals have a tremendous impact on society, but I don’t think rich institutions simply getting richer would be a good outcome by itself, which is one more reason why we need to invest more deeply in the philanthropic infrastructure to support giving beyond the usual suspects. Today, we find that the ultra-wealthy spend about 1.2 per cent of their wealth on philanthropy each year. I would hope to see that number dramatically higher.

In our experience of working in South Africa and India, the amount of cross-pollination between India and Africa is huge. That’s invisible if you’re sitting in New York.

Second, relatedly, I hope to see more money focused on addressing the deep, systemic inequities that plague so many sectors of society. Race, gender, caste, for example, remain in many cases the most powerful variable accounting for disparate outcomes in health, livelihoods, education, wealth. We must confront the root causes of these inequities. For philanthropy, this will entail new forms of grantmaking that centre the voices and decision-making of people in communities and facing different challenges.

Third, I hope that philanthropy supports – or stays out of the way of! – the natural human impulses that lead people to help, support and accompany each other. The burst of mutual aid groups in the face of the recent compounding crises is a powerful example I hope we see more of. As tax law changes are considered in the US, we need to make sure that everyday givers, not just the ultra-wealthy, have incentives to contribute to the common good. A strong philanthropic sector is not an end in itself – it is part of a puzzle that creates a vibrant, equitable, resilient world with opportunities for all to flourish.

Charles Keidan is Executive Editor at Alliance magazine.

Email: charles@alliancemagazine.org.

Twitter: @charleskeidan

This article is being published free-to-read thanks to The Bridgespan Group.

Comments (0)