Nearly 1,200 UK charities have Royal patrons. Mindful that some donors are much less helpful than they think they are, Giving Evidence[1] set out to investigate whether Royal patronages help charities. We could find no evidence that they do. We also found no reason that donors should take a Royal patronage to indicate that a charity is particularly effective.

This is an effectiveness study: we viewed Royal patronages as an intervention in an organisation, and sought to understand what the intervention is and what difference(s) it makes. We had three research questions: what is a Royal patronage, which charities have them, and regarding their effect.

This is an effectiveness study: we viewed Royal patronages as an intervention in an organisation, and sought to understand what the intervention is and what difference(s) it makes. We had three research questions: what is a Royal patronage, which charities have them, and regarding their effect.

The UK Royal family has 2,862 patronages, of which a little under half (1,187) are with UK registered charities. Most charity patronees (1,067) have a single Royal patron though some (123) have multiple Royal patrons.

It is not clear what a Royal patronage is. (This is one of various questions we asked the Palace which were not clearly answered.) The positions carry various titles, including patron, honorary patron, president, honorary fellow, and, in one case, Companion Rat.

The only analysable facet of patronages is the public engagements that the Royal patron does with them. Charities often seem to think that a Royal patron will visit or enable events at palaces which they can use to attract press coverage over donors. In fact, most patronee charities did not get a single public engagement with their Royal patron in the whole of last year: 74 per cent of them got none all year. Only 1 per cent of them got more than one. Some got vastly more, but they are mainly charities set up by the Royals. Those are 2 per cent of the patronee charities but last year got 36 per cent of the public engagements with patronee charities.

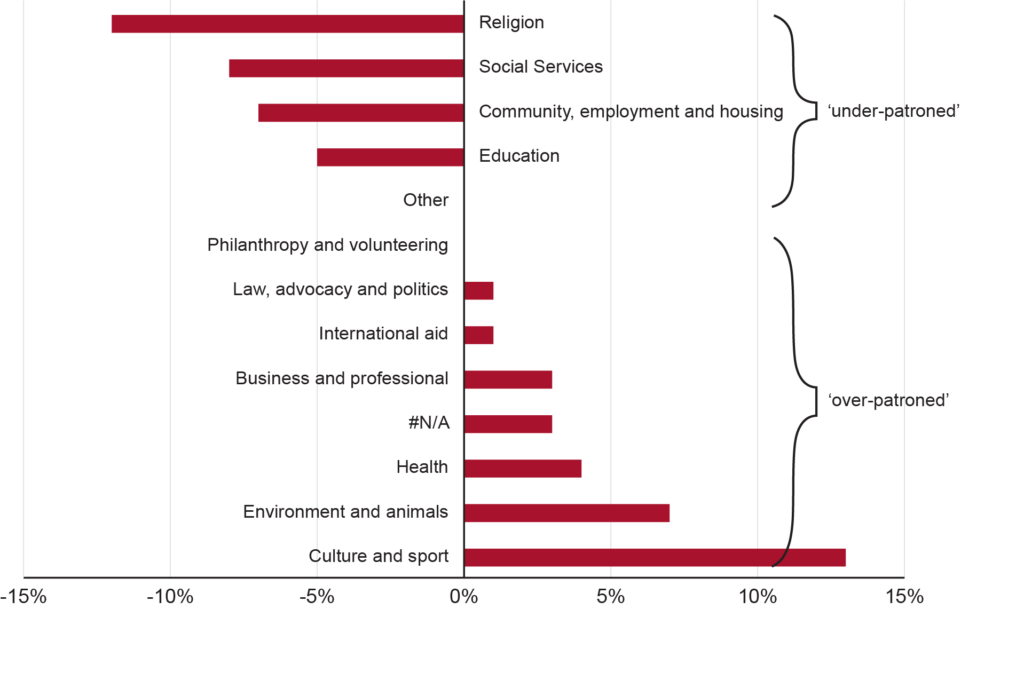

The charities which have Royal patrons are diverse. But they are concentrated in ‘environment and animals’ and ‘culture and sport’ – relatively uncontroversial causes. The sectors with fewest Royal patronages are housing, employment, social services, and religion. They are disproportionately large: patronees’ revenue is (on average) nearly 30 times larger than the average UK charity – and the charities with multiple Royal patrons are on average over 80 times larger than the average UK charity. And they are disproportionately in London, the South East and South West of England – where the Royals’ main residences are. More deprived regions seem under-represented.

This latter is a clue about whether Royal patronages denote quality. Kate (Duchess of Cambridge) is patron of one of the UK’s many children’s hospices: it’s the one in East Anglia, the region which includes Cambridge and her country home in Norfolk. Camilla (Duchess of Cornwall) is patron of one of the UK’s many community foundations: it’s the one in Cornwall. Prince Edward (Earl of Wessex) is patron of one of the UK’s many Roman villas: it’s the one on the Isle of Wight, which is in Wessex. Thus, history and geography seem to play major roles in selecting patronees, and the Palace’s own website talks about the Royals’ personal interest and serendipity being important.

This latter is a clue about whether Royal patronages denote quality. Kate (Duchess of Cambridge) is patron of one of the UK’s many children’s hospices: it’s the one in East Anglia, the region which includes Cambridge and her country home in Norfolk. Camilla (Duchess of Cornwall) is patron of one of the UK’s many community foundations: it’s the one in Cornwall. Prince Edward (Earl of Wessex) is patron of one of the UK’s many Roman villas: it’s the one on the Isle of Wight, which is in Wessex. Thus, history and geography seem to play major roles in selecting patronees, and the Palace’s own website talks about the Royals’ personal interest and serendipity being important.

On the effect of patronages, charities report various benefits e.g., on staff morale, on beneficiaries. We do not deny these. But we are trying to do science, so needed reliable and comparable data about the large number of charities that we needed to analyse. The sole such data are revenue. The potential to raise a charity’s revenue appears to among the Palace’s criteria for selecting charities.

Just looking at graphs of the revenue over time of the patronee charities versus that of comparable charities shows that nothing much happens to their revenue when a patronage starts.

We also looked in much more complicated ways. We used several sophisticated analytical methods: econometric regressions using various combinations of comparator groups and outcome variables. None convincingly found an effect.

Royal charity patronages of course raise a question of public expenditure. The Royal family costs the taxpayer – on the sole estimate we found which includes the cost of their security – £345m per year. If we take public engagements to indicate their workload, 26% of their work is for their patronee charities: equivalent to £90m per year. If that produces no discernible benefit, it may not be good value for money. On the other hand, if Royals do help patronee charities, there is a legitimate question of the process and criteria by which that publicly-funded benefit is distributed, which is currently not clear.

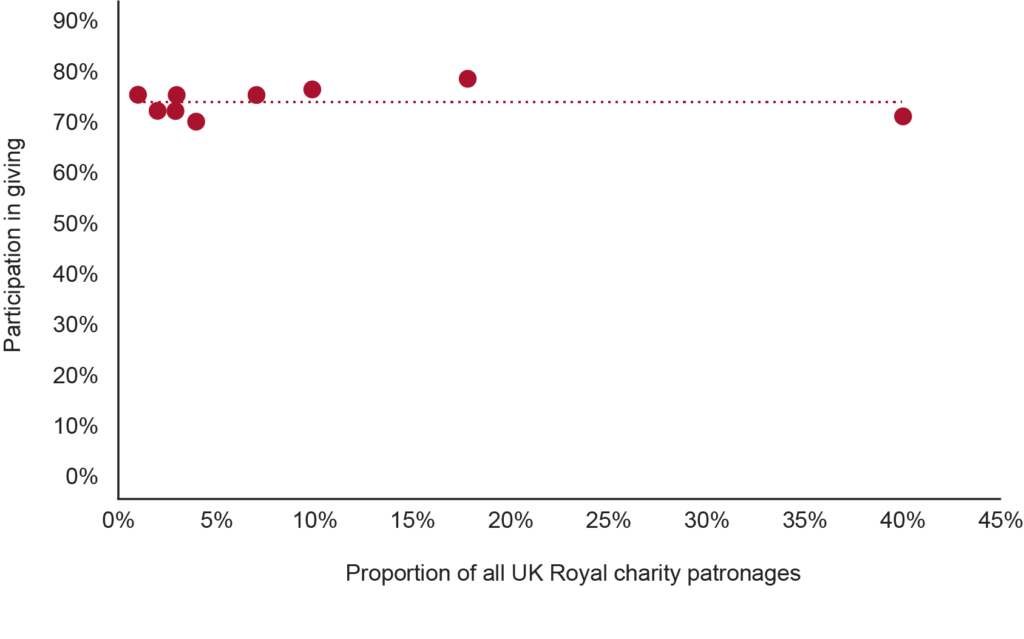

We also looked for evidence of Royals having a ‘macro’ effect on generosity. Data from England showed no correlation between a concentration of Royal charity patronees in a region and the generosity of people in that region. And looking internationally, we found no evidence that a resident Royal family makes a nation more generous. In short, we looked from many angles, and did not find evidence of a beneficial effect from any of them.

All of Giving Evidence’s work is about providing evidence to help charities and donors use their scarce resources to greatest effect. We hope that these data help in that respect.

To read the report, visit the Giving Evidence website. To read more about this subject, check out Alliance magazine’s December 2018 issue spotlighting the world of royal philanthropy.

Caroline Fiennes is Director of Giving Evidence, a consultancy and campaign which enables charitable giving based on sound evidence. She was an award-winning charity Chief Executive, and is a Visiting Fellow at Cambridge University. Find her on Twitter at @carolinefiennes.

Comments (1)