The need for innovation in tackling today’s unprecedented social and economic challenges is generally embraced by foundations. In stark contrast, the need for greater investment in its twin, the research essential to discovering, incubating and testing effective solutions, receives little mention.

As a leading European Union commissioner recently highlighted, however, we may pay a high price for failing to see research and innovation (R&I) as two sides of the same coin and under-investing in it:

‘In the future we will be judged for the investments we . . . make now . . . yet we in Europe remain lethargic, occupied by investments that deliver short-term gains, look safe. This has a stranglehold . . . limiting the potential of . . . European research, science and market‑creating innovation.[1]’

In this context of low European R&I investment compared with Asia and the US, the EU funded a pan‑European study of foundation support for R&I (EUFORI), which reported this summer[2]. In spite of some high profile institutional grants, such as the recent Woods Foundation £5 million package to Robert Gordon University in Scotland to establish a centre of excellence in oil and gas studies, little is known about general foundation spending on R&I.

‘Research investments around Europe show that foundations may achieve even greater returns if they re-balanced spending from pragmatic, often untested, projects toward longer‑term and forward‑looking research, knowledge and innovation.’

But research investments around Europe show that foundations may achieve even greater returns if they re-balanced spending from pragmatic, often untested, projects toward longer-term and forward-looking research, knowledge and innovation.

Many of the largest single foundation grants are made to research and higher education institutes, and the EUFORI study revealed that the spending of European foundations on R&I is worth an annual 4.5 billion euro. This represents just 8.5 per cent of foundation spending[3], however, though historically European foundations have a long tradition of investment in scientific, economic or social progress.

Such foundations were often established by founders themselves at the leading edge of the successful research development and industrial enterprise of their day, as examples like Robert Bosch Stiftung, Germany, Wolfson and Nuffield Foundations, UK, Fondazione Giovanni Agnelli, Italy, and Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, Sweden, illustrate.

But while several foundations today continue these traditions, many others either fail to see the value of investment in research, or regard it as a luxury they cannot afford.

How do foundations support research?

The EUFORI results show the vast majority of R&I foundations (83 per cent) support applied research, with its direct relevance for current problems and issues. Nearly two-thirds (61 per cent), however, also take more forward-looking and visionary approaches through funding basic and ‘blue-sky’ research that builds knowledge in more open and theoretical ways.

Investing in research and innovation can help us find sustainable solutions to environmental problems. Credit: Tim J Keegan

A vital element of research funding strategy (55 per cent of foundations) involves retaining talent and building expertise through providing opportunities for young or individual researchers to progress their research careers (funded by 43 per cent). This is through post-doctoral training and innovative research prizes such as those of the Greek John S. Latsis Public Benefit Foundation to encourage individual excellence.

‘A vital element of research funding strategy (55 per cent of foundations) involves retaining talent and building expertise through providing opportunities for young or individual researchers to progress their research careers (funded by 43 per cent).’

Foundations also invest in higher education institutions (48 per cent) and in vital new research fields. These prominently include climate change, where new centres have been funded in Berlin (Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change) and Oxford University (Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment).

With feet always in the worlds of practice and policy, however, R&I foundations notably maintain a strong focus on users: 78 per cent support research knowledge dissemination. One example is the Norwegian Gjensidige Foundation which funds ‘knowledge centres’ where participants can learn more about mathematics, science and technology through experimenting.

A dividing melanoma cell. Foundation spending matches or surpasses that of governments in fields such as cancer and genome research. Credit: Wellcome Trust.

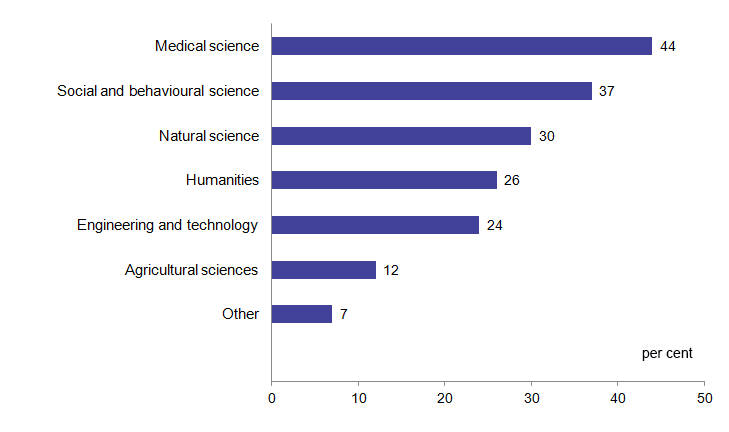

Which areas and topics get funded?

The major health and bio-medical foundations dominate foundation R&I spending. Medical science attracts 63 per cent of total R&I charitable spending, from 44 per cent of R&I foundations, for example, the high profile Wellcome Trust, Institut Pasteur and Dutch Cancer Society.

While overall, the non-profit sector contributes just 0.02 per cent of the 2.07 per cent of GDP dedicated to R&I in Europe, foundation spending matches or surpasses that of governments in fields such as cancer and genome research. One huge gain from the non-profit nature of genome research funding is that data output has been maintained within the public domain and its fruits accessible to all.

While rather overshadowed by the big medical science organizations, foundations also make a huge contribution to research in topical social issues, with 37 per cent providing funds for research in areas including poverty, minorities, rights, democracy, citizenship and cultural identity.

The UK’s Joseph Rowntree Foundation and Trust for London have used research to highlight the persistence of poverty and deprivation in spite of growing individual wealth, while the Barrow Cadbury Trust supports research around fairer and more effective approaches to young and ex-offenders.

‘Powerful collaborations around knowledge development and social change are a key strength of foundation investment in R&I.’

With two-thirds of foundation research support distributed at national level, foundations often fund research on their specific country issues. The Francisco Manuel dos Santos Foundation, for example, funds research on Portuguese society and its major problems as part of a drive to stimulate awareness and discussion.

Research partnerships

Powerful collaborations around knowledge development and social change are a key strength of foundation investment in R&I.

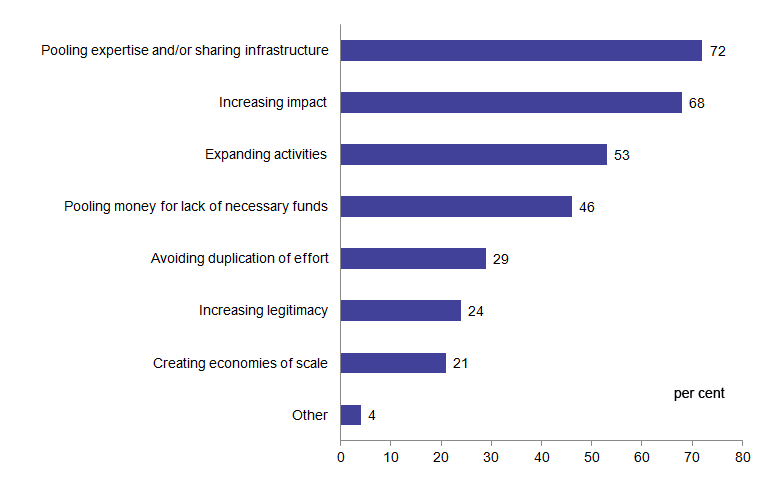

Unsurprisingly, foundations turn to universities as main partners (38 per cent), but companies (20 per cent) and governments (16 per cent) are also involved. The prime motivation for partnership is the sharing of expertise and infrastructure resources, though other strong motivations include the potential for greater impact.

Foundation motivation for research partnership

Source: EUROFORI Study: A network of experts in 29 countries polled 12,000 foundations – the results are based on 2,113 who responded.

Safety, risk and barriers

Through funding, research foundations are making a significant difference to our theoretical and practical understanding of areas from health, science and enterprise to poverty, migration, crime, human development and political co-operation. However, foundations have conflicting perspectives on research investment.

Some see it as the safe and conservative option where foundations want to make large and iconic funding commitments. The funding largely targets individuals or institutes with proven track records working in well-established fields. It often invests in young talent, where the prospects of return are high.

Social investment or venture philanthropy, in which finance is made available with a view to longer-term though difficult-to-quantify social returns, is often regarded as a riskier and more innovative approach to social change. Yet it is important to understand that research investments often carry the same challenges and opportunities as other social investments. They can involve a huge leap into the unknown, with no guaranteed return on investment.

As the Wolfson Foundation states:[4]

‘. . . the foundation’s funding of scientific research is based on the underlying philosophy that funding the most outstanding science – whether fundamental or applied – is the route to the most significant (if often unpredictable) impact.’

These challenges of the unknown in research funding are most starkly spelled out by the engineering entrepreneur James Dyson, whose foundation supports education for innovation in design:[5]

‘Tenacity and self-belief are crucial. As a young inventor, you come up against obstacle after obstacle. Quite often the challenges can seem insurmountable, and it’s only your own bloody-mindedness that will see you through.’

To foundations grappling with daily evidence of immediate and growing social need, research can seem of little relevance. But investment in R&I has a key place in finding longer-term and sustainable solutions to our global environmental and social challenges.

The question is not whether foundations can afford to invest in R&I, but whether they can afford not to.

Cathy Pharoah is visiting professor of charity funding at Cass Business School, City University and author of the UK chapter of the EUFORI report. Email catherina.pharoah.1@city.ac.uk

Footnotes

- ^ Carlos Moedas, Commissioner for Research, Science and Innovation.

- ^ Barbara Gouwenberg, Danique Karamat Ali, Barry Hoolwerf, René Bekkers, Theo Schuyt and Jan Smit. (2015) EUFORI Study. Luxembourg, Publications Office of the EU.

- ^ EFC estimates that annual spending by foundations in Europe is around 53 billion euro in total.

- ^ http://www.wolfson.org.uk/funding/science-and-medicine/research

- ^ https://www.philanthropy.cam.ac.uk/impact-of-your-gifts/an-interview-with-sir-james-dyson

Comments (0)