‘As an outsider, you are more able to question the received wisdom, to challenge people’s basic assumptions.’

Just under ten years ago, Judith Rodin moved from being president of the University of Pennsylvania to become president of the Rockefeller Foundation. What is exciting about running a foundation, she told Caroline Hartnell, is having the freedom to take risks, something you can’t do as much when running a university. She also talked about being an outsider, about leadership and mentoring, and about what distinctively women bring to leadership positions.

You moved from an academic institution to become president of the Rockefeller Foundation in 2005. What did you find most surprising or even difficult about the different institutional culture of a big foundation?

I’d like to start with the similarities. Both universities and philanthropies have a very powerful role to play in shaping dialogue and mobilizing action. So they share a significant overlap in purpose. But universities’ impact is through education and research, whereas philanthropy’s mission is broader: it’s to develop and implement all kinds of interventions that are focused on improving people’s lives and livelihoods. So the possibilities are greater in philanthropy and that is exciting.

I think one of the biggest differences, and one that I’ve really tried to push at Rockefeller, is that philanthropy has both the capacity and the obligation to take risk. In America, in particular, we have tax advantaged dollars, and I like to argue that we are America’s risk capital, which give us the responsibility to be risk takers. We’re free to dive right to the heart of the biggest problems in the world. I have found it liberating to see risk in this way, because it allows us to innovate, to test, to change course. Running a university doesn’t give you that kind of freedom and flexibility.

Do you feel the philanthropy sector is embracing this potential to take risks?

I can only speak for the Rockefeller Foundation, which is the institution that I know best. I did not think that the foundation was taking sufficient risks when I came. It had become comfortable with a group of grantees the foundation had gotten to know well and a group of issue areas that it had worked on for a long time.

What my team and I have tried to do here is to build an environment that encourages risk, that encourages staff to experiment and to think outside the traditional philanthropic model. We’ve spent a lot of time collaborating with innovation experts like IDEO and others to build up that skill set inside the foundation and inside our grantee organizations. We have a larger and much more diverse group of grantees now, and they are each aggregated around an initiative. They all understand the initiative strategy and what piece of that strategy and what set of interventions their grant relates to. And there’s a lot of feedback from our staff and our grantees about how things are working.

What do you think you brought to the foundation as an ‘outsider’ to the sector?

As an outsider, you are more able to question the received wisdom, to challenge people’s basic assumptions, because you haven’t grown up in that culture with that same knowledge base; you see things differently. As an example, when I was a professor at Yale, I loved teaching introductory psychology to freshmen because they didn’t know anything about the field and they asked really tough questions of me. It made me reframe my own thinking and rethink all the things that I believed were true. So I raised those kinds of questions when I joined Rockefeller.

I had a set of experiences as a leader in academia that taught me that, in order to be a high-performing organization, you need a culture that is inclusive and builds mentorship and you have to work towards a common goal. As a research psychologist, I was accustomed to collecting and analysing data, which helped in developing what we now call our emergent strategies: you develop a strategy, you implement, you monitor, then you see what is working and what isn’t and then you redevelop the strategy. That approach has allowed us to be much more flexible, to be able to adapt more quickly when we see something isn’t working – but only when the evidence demands it. That approach is very systematized in our staff now.

Were there any disadvantages to being an outsider?

One clear disadvantage is that I didn’t know either the Rockefeller Foundation in particular or the foundation world in general, which meant that I had a steep learning curve. But I could draw on the extensive archival material of the Rockefeller Foundation, and because I’m an empirical scientist, I know how to ask questions to try to learn quickly. But when you ask a question as an outsider, people can find it threatening, and I experienced some of that.

How have your own experiences affected your views on hiring foundation staff?

At Rockefeller, we’re working to build greater resilience and more inclusive economies, and the expertise needed for that doesn’t live in one specialized field of learning or in one sector. So we are recruiting from many sectors – from philanthropy, the development sector, government, academia and the private sector. We have an amazing mix of leaders who reflect that, and it’s in that mix that I think we have our greatest strength. That mix helps us to understand the complexity of the problems of today’s world, and makes the initiatives that we develop and the work that we do more appropriate to them. When we go into an area we do a systems map of the terrain: who all the actors are, how we expect them to respond, whose work we can leverage, who we have to watch out for.

What skills, values and attributes do you believe are most important for foundation leaders today?

I think you have to take a ‘learn as you go’ approach. You can’t plan everything in advance. The problems are too complex. You have to see where momentum is building and work out how to capture it and ride it.

When you do that, though, you also need to know when to pull back, when the energy and dynamism aren’t there. So what we look for is people who understand the preciousness of our risk capital, who welcome the opportunity to innovate and pilot the next great thing, while always being both able and willing to learn from the past and to measure the impact of the innovations as they’re going along.

People also have to be personally ambitious as well as ambitious for social change. We don’t want Rockefeller to be a place where people come and park themselves and get a pay cheque and just leave at the end of the day. It’s such a privilege to have resources that allow us to try to change things in the world that are going wrong and can be improved, so we look for people who understand it is a privilege and responsibility and are willing to work hard for that purpose, who see this as an extraordinary opportunity.

I understand that you mentor Rockefeller staff to help develop their leadership qualities and that several are now in prominent positions in other foundations, including Darren Walker. How do you go about mentoring others in order to bring out these qualities?

When I came to Penn as president, I was struck by the work of Bill George, who says that being a mentor is most satisfying and most beneficial when it creates mutual learning, and that is what makes mentoring both challenging and powerful. It means that we’re not just displaying the things that people admire and want to emulate; we’re also expressing the uncertainties, ambiguities and unexamined possibilities that we feel in our own lives and we’re frank about the trade-offs and course corrections we’ve made. That’s what real mentoring is. I’ve got as much as I’ve given in those roles. It’s part of gaining maturity and wisdom and it’s a responsibility to care about those who are going to come after us.

And I’m extremely gratified by the outcomes. There are eight men and women that I mentored at Penn who have become university presidents. At Rockefeller, for example, there’s Darren, now president of Ford, Nick Turner, who’s gone on to be head of the Vera Institute of Justice, and Anthony Bugg-Levine, now heading up the Non-Profit Finance Fund. So I don’t consider people departing for high-level positions a failure, I consider it an accomplishment. It’s how organizations and leaders ought to judge themselves.

What is the process? Do you meet regularly?

No, it can be infrequent, but not so infrequent as to not make a difference. It can sometimes even be a casual interaction that you didn’t set up as a mentoring meeting. My favourite example involves Nick Turner. We have a regular meeting of our senior leadership at Rockefeller. People were coming late and I told them it had to stop. At the next meeting, Nick had to drop the kids off at school. One of them had a meltdown so he raced in about 35 minutes late, and he said I glared at him. He came to my office afterwards to explain and I said to him, ‘Nick, I’ve been a parent, I’ve been in that situation. I understand.’

Then I told him of a comparable experience when I was chairing the psych[ology] department at Yale. I was always late picking up my son from day care, so the staff at day care said, ‘We have families too, and you’re always late. The next time you’re late, we’re going to put Alex out on the street.’ So I was chairing a department meeting and it was going on and on. I was looking at my watch and my heart was racing, and I finally stopped some guy in mid-sentence and said, ‘This meeting is over. I’ve got to go pick Alex up at school.’ I felt awful. The next day, one of my colleagues came to my office and asked, ‘Do you think I could go to my kid’s soccer game at 3.30?’ I asked him, ‘Is this because I’m now giving you permission to show that you care about your children as well as your professional life?’ It changed the department.

When I told Nick that story, it was a mentoring moment. After that, we talked a lot about parenting and career and ambition. But if I hadn’t been willing to share my experience, I would only have been telling him I understood. The sharing part was the mentoring.

You were the first woman leader at the Rockefeller Foundation and that was also true at Penn. What do women bring to leadership? And what’s lost if there aren’t enough women leaders?

As a point of pride, the Rockefeller Foundation has more women on its board than men and we have the first or second most diverse board in American philanthropy – something I’ve worked hard to foster.

I think women focus on equitable policies in the workplace, so there’s tremendous support for policies to invest in human capital when there are women in the C Suite or on boards. I don’t think it’s coincidental that, as there are more women in boardrooms and in the C Suite, we’re seeing the kinds of innovations that we’re seeing today. Women have a great capacity to listen to other people’s ideas and really try to understand them whereas often, in boardrooms and in executive suites, people don’t listen, they’re waiting to get their turn to talk.

I think where women still need to do better is in reaching out and embracing the power of both professional and personal networks. Men have done this for centuries. Networks are important because they support a woman’s individual career advancement but they will also keep her grounded and self-aware as she climbs the ladder. I talk a lot about that when I talk to younger women.

As a member of a number of boards, I seek out opportunities to talk to the women in the organizations – with the support of the CEO, of course. I see that as part of my responsibility as a board member. I can’t call it mentoring, but it’s a good opportunity both to talk about what we think we bring to the board as women, and to hear from senior women what the organization could do that we could help to facilitate in our role as board members. I’ve seen lots of women do that and I think it adds to organizational effectiveness.

To truly create change, we must fix the systems that keep women all over the world from accessing opportunity, property rights, legal representation, and healthcare. That’s why we at the Rockefeller Foundation look at every initiative with a gender lens. For example, we know that in almost every part of the world, but particularly in low-income regions, women are the last to seek out preventative healthcare because they are most focused on getting care for their families.

This kind of thinking, quite frankly, often doesn’t happen without the rise of women through the ranks of leadership.

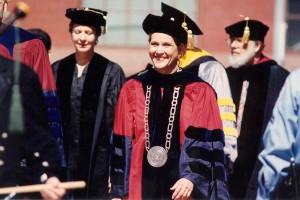

Judith Rodin has been president of the Rockefeller Foundation since 2005. She was previously president of the University of Pennsylvania, and provost of Yale University. She was the first woman named to lead an Ivy League Institution and the first woman to serve as the Rockefeller Foundation’s president.

Comments (0)