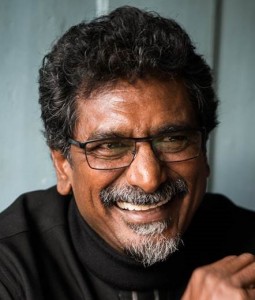

As social justice campaigner, trade unionist, government minister – Jay Naidoo has seen most sides of the development process. What’s the main lesson he’s learned from all this experience? That the whole process is based on an outdated view of the world. The best of intentions notwithstanding, those who run development programmes are increasingly remote from the people they aim to serve. What’s needed, he tells Caroline Hartnell, is a new approach – to measuring the impact of development projects, and to devising them in the first place. Time to start listening to the voices of ordinary people, he urges.

The time we live in, says Jay Naidoo, has undergone ‘a technological and knowledge revolution that has probably had a bigger impact on the way we organize our society, the very nature of work and communications, than the industrial revolution had in its own time. Yet we are trying to solve the problems of development using institutions and thinking that is, in many cases, fairly obsolete.’

The result, he thinks, is that development has become professionalized and ‘cut up into projects’ to such a degree that ‘the very people that we seek to serve have become bystanders. The voices of ordinary people at the grassroots level, facing many of the world’s challenges, are not being heard’.

And so he started to think about monitoring and evaluation and measurement, which have become so much part of the new lexicon of thinking about development. ‘And the question is, “who is asking the question?” and “who is benefiting from the answers?”’

Ignoring the voices of ordinary people

It sometimes comes about that people’s voices end up being ignored for understandable reasons. He gives the example of South Africa. At bottom, he explains, apartheid was a ‘cheap labour system’ based on racism which, in the process, stole people’s dignity. It produced a civil society driven by notions of human dignity and social justice. With the establishment of a democratic constitution in South Africa, the state to some extent usurped civil society’s role, believing that ‘the main instrument for delivering the better life that we promised our people in 1994 was the developmental state. I think we all missed the plot there of rethinking civil society. In a sense, it was the passion and activism and energy of people that paralysed the apartheid state and forced it into negotiations with us. We should have harnessed that dynamism and energy, and made them partners in the way we delivered it’.

As the voices of ordinary people are marginalized, he argues ‘we have created a language, a system, particularly a measurement system, that has alienated the very people that should be part of making development work. No matter how good our cause, no matter how much money we pump into it, it still ends up in a situation which falls on its back and people feel incredibly frustrated’.

What do we need to do now?

‘I basically think we have to rethink everything.’ This sense of anger and frustration is particularly pronounced among the young, says Naidoo. Young people don’t trust ‘people of our generation’, believing that they are ‘very much part of the system’, or the institutions that we have created. The core demands of the Arab Spring revolts were ‘about social and economic inclusion, human dignity, social justice, corruption’. If you look at ‘student strikes in Chile or Quebec, or the anti-corruption movement in South Africa, there’s this tremendous upsurge of anger at the growing inequality in the world, and a growing sense of exclusion’. Often, people are not members of civil society organizations because those organizations themselves are seen as discredited. ‘Why is it,’ he asks, ‘that in South Africa in 2009, out of 31 million people that had a right to vote, only 25 million registered to vote and only 18 million voted?’ The vast majority did not vote ‘for the democracy that many people in my generation paid with their lives for’ because they ‘still experience the same marginalization and poverty and exclusion that they did under apartheid’.

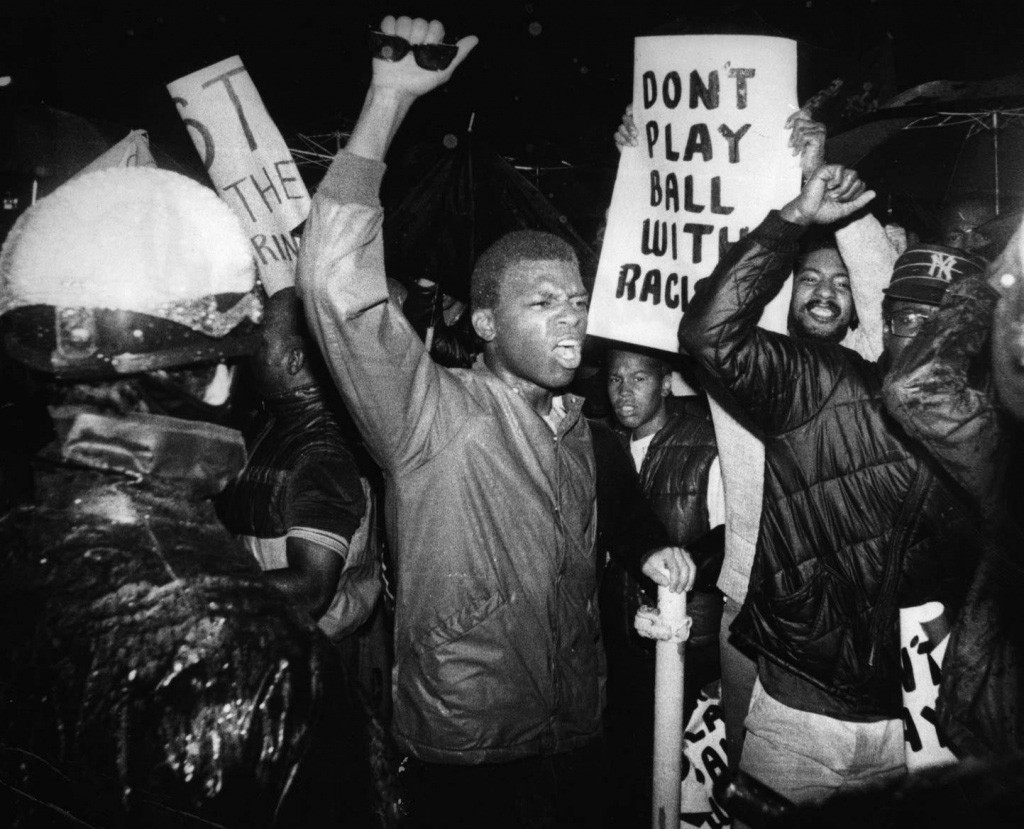

Unidentified demonstrators on 22 September 1981, protesting against the national rugby team the Springboks, because of South Africa’s policy of apartheid. Credit: Times Union Archive Photo / Skip Dickstein.

What are we measuring?

The development industry, says Naidoo, has taken an increasingly compartmentalized approach to problems, dividing them up into projects and then measuring the impact of each project. What we need to do, he believes, is ‘to measure the system and not the individual indicators. People have incredible resilience – most of them raise families on less than a dollar a day – yet we do not think that they contribute to finding solutions to the problems that they experience’. The result is that measurement has been ‘dominated by bean counters’ who have had very little experience of the problems they are confronting.

‘The development industry…has taken an increasingly compartmentalized approach to problems, dividing them up into projects and then measuring the impact of each project.’

For him, the central issues of measurement should be ‘who is measuring who?’ and ‘what are we measuring?’ and ‘how does the measurement of what we’re doing change how people are living their lives?’

‘We’ve got to turn this on its head,’ he says, ‘and constituent voice is, I think, the most sustainable way of addressing poverty, creating livelihoods, addressing and building social cohesion.’ And it’s not just a question of getting feedback on what’s been done; it’s about using the views of constituents to frame development policies in the first place.

Shut your mouth and listen to the people

‘One of the most important lessons I learned about development in the late 70s, when I went from being a student activist to being a trade unionist, was to shut my mouth and listen to the people. Together you start to co-create the vision, the strategy, the goals you set, and the tools you need.’ If they ever knew it, development theorists have forgotten that lesson, he thinks. For them, people are the victims rather than the source of the solutions we need to solve the problems of development.

‘One of the most important lessons I learned about development in the late 70s, when I went from being a student activist to being a trade unionist, was to shut my mouth and listen to the people.’

For Jay Naidoo, the most important part of the debate about development is about ‘constituent voice, enabling communities to determine what their problems are, what the solutions are, what resources they need, how they would use the resources, how they measure. And it’s not the part that scientists and theoreticians write books about’.

The technology now exists to build what he calls a ‘constituent loop’ into many projects. ‘When I was Minister of Communications in 1996 in South Africa, we had fewer phones in Sub-Saharan Africa than the island of Manhattan. Today, there are more than a billion phones; we have a generation more connected than ever before. Constituent feedback is not a very expensive thing to do so why isn’t it a standard part of development?’

Where do you begin?

A good place to start might be the corporate sector. He gives the example of a mining company in South Africa. As part of their licence agreement, the company will have a social plan, a community plan. What a difference it would make ‘if their starting point was: let us sit down with a community and understand, first of all, what the priorities of that community are, what they see as their problems, what they see as their solutions? And if they had a consistent feedback mechanism’.

It’s about legitimacy and ownership, he says. ‘Legitimacy and ownership are critical to the success of everything. At the end of the day, if people do not feel that they own the process, they will not own the outcome. If we continue focusing on outputs that meet our needs because we’ve got to answer to a funder or a donor, we miss the point that the real thing we should be measuring is outcomes – what people themselves believe they have achieved, not us as the catalysts, or the agents of delivery.

‘So you could build this feedback loop, based on constituent voice, into many projects. This should not be a pilot thing, this should be a standard, the starting point for any entity – company, government, bilateral agency, NGO, foundation. We need to make it part of our daily practice.’

This would be one step towards turning what he calls the politics of measurement on its head, with ‘the people on the top and the experts at the bottom, with the people telling them what to do!’

Jay Naidoo is chair of the Board of Directors and chair of the Partnership Council of the Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN). Email jnaidoo@gainhealth.org

Comments (0)